Location Determinants of Food Manufacturing in the United States: The Competitiveness of Nonmetropolitan Counties

May 19, 2010

PAER-2010-05

Elizabeth Dobis, Graduate Student, Dayton Lambert, Assistant Professor and Kevin McNamara, Professor*

The location of a new food manufacturing firm in a rural county brings employ-ment opportunities to communities which can increase farm household access to off-farm employment. The location of a food processor also can positively impact farm income if the processor purchases local or regional agriculture products for processing. For instance, corn grow-ers selling to a local wet corn miller might increase their income from price premiums, reduced marketing costs, or lower transportation costs. However, food manufacturers, like other manufacturers, make location decisions to minimize costs. Leaders in communities seeking to attract food manufacturing or other manu-facturing investment would benefit from understanding what influences manufacturing location investment decisions. The following discussion describes firm investment decisions and the factors affecting them. These factors are divided into market factors, agglomeration economies, infrastructure, labor, and fiscal policy. The discussion draws on research on food manufacturing and other firm location decisions.

Selection Process and Firm Types

Firms employ a two-stage selection process when choosing a location for a new manufacturing facility. The goal of this process is to maximize a firm’s profits through obtaining the lowest possible production costs. The first stage is the selection of a region based on broad company objectives such as expanding to a new region of the United States. Once the regional decision has been made, firms seek a low cost site within that region. The attributes of a site that food manufacturers use to make their location decision are access to input and product markets, agglomeration factors, labor attributes, infrastructure, fiscal characteristics, and social capital. Each of these determinants influences the costs firms incur (discussed further in the next section). By evaluating the unique combination of attributes at each potential location, firms are able to identify sites that increase profit potential.

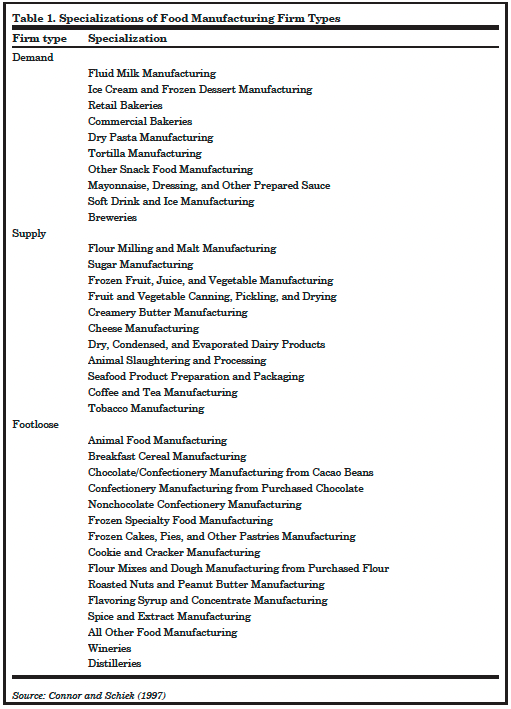

Food processing firms have different needs depending on the products they manufacture. Recognizing this, John Connor and William Schiek clas-sified food processors into three cat-egories based on their cost structure: demand oriented, supply oriented, and footloose (Table 1). These classifications differentiate firms through common production charac-teristics. Demand oriented firms tend to produce fragile, perishable, or bulky food items. Bakeries, brew-eries, milk processing facilities, and pasta manufacturing facilities are examples of demand oriented firms. Their cost structure is dominated by distribution costs – costs associ-ated with getting their product to market. They, therefore, tend to locate near consumers to decrease these costs. Supply oriented firms have cost structures dominated by what they use to make their products. They are likely to locate near inputs to reduce their procurement costs. Examples include flour milling, fruit and vegetable canning, animal slaughtering, and cheese manufactur-ing businesses. Footloose firms do not have cost structures that are dominated by either input or dis-tribution costs. These firms include breakfast cereal, chocolate, cracker, and spice manufacturing. They are inclined to locate where transporta-tion, business services, and capital are easily accessed.

Rural and urban areas offer different mixes of the cost saving characteristics firms desire. For instance, urban counties offer large markets to purchase final goods, whereas rural counties offer easy access to agricultural inputs. Because of this, patterns may be present in the behaviors food processing firms exhibit when selecting new manu-facturing sites. Dayton Lambert and Kevin McNamara looked into these patterns and determined that some hold for all firms while others are specific to a food processor’s cost category (discussed above).** These patterns are presented below.

Determinants of Firm Location

Location determinants of food manufacturing facilities occur in different combinations over the geography of a state or country. The amenities available in and around Indianapolis, Indiana are very different from the amenities in a rural Indiana county like Fulton. Firms evaluate potential sites for a new manufacturing facility on the basis of how well they meet the firm’s production needs and they often evaluate sites in several states. Communities seeking to attract new manufacturing investment, there-fore, are often competing with sites in adjacent states rather than with other sites in the same state.

As mentioned previously, the characteristics food manufacturers use to make their location decisions are access to input and product mar-kets, agglomeration economies, labor attributes, infrastructure, and fiscal characteristics. The site where distri-bution, procurement, and production costs are minimized is determined by the location and size of individual firms’ product and input markets. These low cost sites are ideal for increasing profits.

Agglomeration economies are cost savings related to an accumulation of business activity in and around a geographic area. These cost savings occur because inputs and service providers are nearby. Additionally, when a group of similar manufactur-ers locates in the same geographic area, such as RV manufacturing in Elkhart County, cost savings occur due to a skilled labor force and infra-structure costs that can be shared among firms.

Infrastructure determinants allow for cost savings due to the physical or natural characteristics supporting community and business activities. Infrastructure determinants can include land availability, transpor-tation networks, and educational institutions. Business schools and junior colleges are an important part of infrastructure because they provide skilled employees and access to technological innovation. Labor quality and availability are important cost saving determinants for manu-facturing firms because locations with diverse populations allow better job matches. Higher quality workers are also more productive.

Fiscal determinants include state and county expenditure patterns and tax policies. It is difficult to know how fiscal determinants will influence firm decisions because tax holidays are often given to firms to make a particular location more enticing.

Table 1. Specializations of Food Manufacturing Firm Types

All three food manufacturing types share some common location needs. For instance, urban centers are more likely to attract all types of new food manufacturing firms. Highly populated rural counties and counties with higher per capita income are also more attractive. This is most likely due to labor avail-ability and quality as well as county expenditures. Characteristics of the labor available for hire are very important to firms. Diverse urban counties like Marion County (India-napolis) draw all firm types due to the variety of employees available. This variety increases the chance of acquiring employees well-suited to positions in the new facility being constructed. This is also the reason why business schools and junior col-leges draw all food manufacturing types to urban counties. Agglomera-tion is important for rural counties to attract all manufacturing firms because of the cost savings it pro-vides. However, contrary to general thought, access to interstate high-ways may not attract firms of any type to rural counties.

Demand oriented firms’ location decisions are driven by their prox-imity to consumers. This results in generalized patterns within this production type. Demand oriented firms find that the further rural counties are from the nearest urban county, the less attractive they are as facility locations. This is because the greater the distance to a firm’s product market, the higher the transportation costs. Thus, urban counties, with access to interstate highways, tend to attract demand oriented firms. Counties where a majority of the population belongs to a single racial or ethnic group (as categorized by the US 2000 Census) appear to be more attractive to demand oriented firms in rural counties, but the presence of unions in these counties is a deterrent. Demand oriented firms are also attracted to rural counties where public expenditures are relatively larger than local tax revenue.

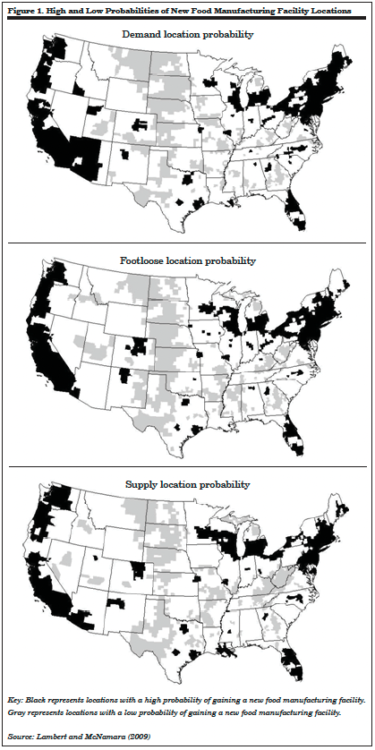

Figure 1. High and Low Probabilities of New Food Manufacturing Facility Locations

Supply oriented firms choose to locate in or near counties that offer ready access to the raw material that dominates their cost structure. Therefore, it might make sense for rural counties with a relatively large supply of the commodity a processor uses to focus on attracting that type of supply oriented firm. Even if the firm does not locate in the county, a location near the county could offer growers lower transaction costs in marketing, increasing farmer net income. This situation may occur because supply oriented firms tend to prefer urban counties as they may provide access to interstate highways and larger unemployed populations.

Footloose firms do not make their location decisions solely on how close they are to their raw materials or consumers. While access to input markets is important for footloose firms, they seem to be most con-cerned with labor determinants. Labor quality attracts footloose food manufacturers to rural coun-ties. Business schools and junior colleges also draw footloose firms to rural counties. Thus, it seems that footloose food manufacturers prefer to locate in rural counties where business schools and junior colleges provide a pool of trained and productive potential employees. Additionally, the presence of unions discourages the location of footloose firms in urban counties.

Considering the location characteristics that are important for food manufacturing firms, national location trends emerge. Figure 1 shows sites where food manufactur-ing firms are likely to locate in black and sites where they are not likely to locate in gray. These trends indicate demand oriented, supply oriented, and footloose firms are likely to locate in the Northeast. The Corn Belt draws supply oriented and foot-loose firms as well. In general, urban centers are more likely to attract all types of new food manufacturing firms. The further a county is from an urban center, the less likely a firm is to locate in that county.

Conclusion

The selection of a county as a new site for a food manufacturing firm can increase the economic well-being of that county through higher farm incomes and more employment. Man-ufacturers make these site selections through a combination of product and input markets, agglomeration economies, infrastructure, labor characteristics, and fiscal policy. Because the preferences of demand oriented, supply oriented, and footloose firms to reduce costs vary, whether they locate in urban or rural counties is unique to individual firms. Access to agglomeration economies, product markets, labor quality, and workforce trainability is especially important to firms locating in rural counties. Additionally, all food manufacturers prefer to locate in and around urban areas or in rural counties with access to product and input markets and agglomeration economies. This indicates that a “one-size-fits-all” approach to attract-ing and retaining food manufacturing facilities may not work and policies may need to reflect the strengths and weaknesses of individual locations.

References

Connor, J. M. and W. Schiek. Food Processing: An Industrial Powerhouse in Transition, 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons: New York. 1997. Lambert, Dayton M. and Kevin T. McNamara. “Location Determinants of Food Manufacturers in the United States, 2000-2004: Are Nonmetropolitan Counties Competitive?” Agricultural Economics. 40 (2009):617-630.