Trends in Farmland Price to Rent Ratios in Indiana

July 26, 2021

PAER-2021-11

Author: Michael Langemeier, Professor of Agricultural Economics

Despite increasing by 15.5% in 2021, farmland prices in west central Indiana are still 2.4% below their peak in 2014. Compared to historical prices, however, farmland prices in west central Indiana are 88% higher than they were in 2010 and 410% higher than they were in 2000 (for current land values see Kuethe in this edition of PAER). Concerns are periodically expressed by many investment analysts that farmland prices are higher than justified by the fundamentals. One justification for this concern is that previous research has established the tendency of the farmland market to over-shoot its fundamental value.

A standard measure of financial performance most commonly used for stocks is the price to earnings ratio (P/E). A high P/E ratio sometimes indicates that investors think an investment has good growth opportunities, relatively safe earnings, a low capitalization rate, or a combination of these factors. However, a high P/E ratio may also indicate that an investment is less attractive because the price has already been bid up to reflect these positive attributes.

This paper computes a ratio equivalent to P/E ratio for farmland, the farmland price to cash rent ratio (P/rent), and discusses trends in the P/rent ratio. We use land value and cash rent data for the 1960 to 2021 period for west central Indiana to illustrate the P/rent ratio. Data from 1975 to 2021 were obtained from the annual Purdue Land Value and Cash Rent Survey. For 1960 to 1974, the 1975 Purdue survey numbers were indexed backwards using the percentage change in USDA farmland value and cash rent data for the state of Indiana.

Price to Rent Ratio

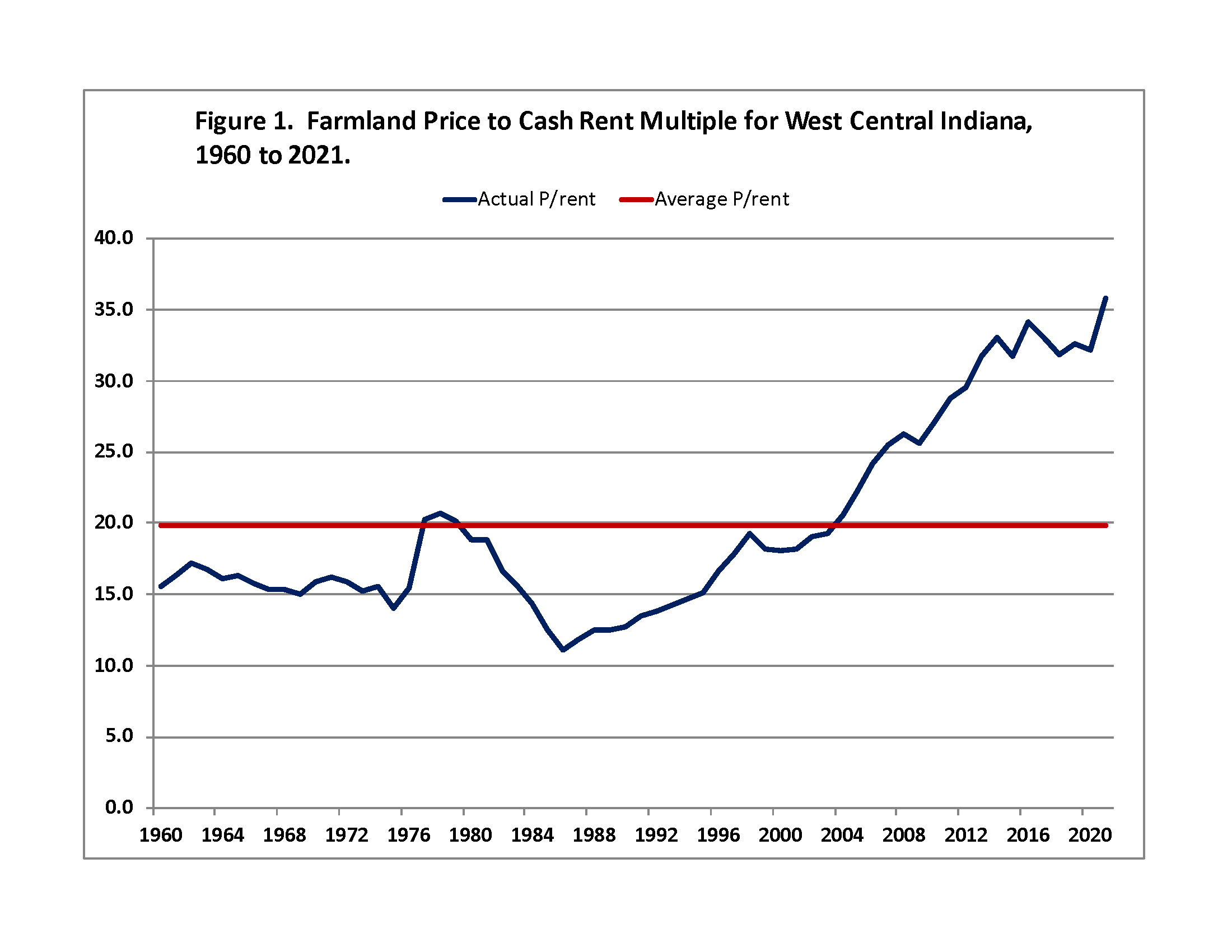

The P/rent ratio for west central Indiana averaged 19.8 over the 61-year period from 1960 to 2021 (Figure 1). The peak P/rent ratio before 1990 occurred during the 1977 to 1979 period. The P/rent dropped substantially from 1980 to 1986 reaching a low of 11.1 in 1986. The rise from around 15 in 1976 into the 20s and down to 11.1 in 1986 corresponds to what is viewed as the bubble in farmland prices that was followed by one of the most difficult periods in history for production agriculture (i.e., the early-to-mid 1980s).

Figure 1. Farmland Price to Cash Rent Multiple for West Central Indiana, 1960-2021

The P/rent ratio has been above the long-run average since 2004. From 2004 to 2014, the P/rent ratio increased from 20.6 to 33.0. Since the peak in land values in 2014, the P/rent ratio has ranged from 31.7 in 2015 to 35.8 in 2021. The current value of 35.8 is relatively high compared to the historic average of 19.8 and a previous high of around 20, and thus at least raises concerns that current farmland prices are overvalued in relationship to returns. Having said that, one of the reasons often mentioned as a major explanatory factor associated with the recently high P/rent ratio is low interest rates. The average interest rate on 10-year treasuries from 1960 to 2021 was 6.1%. The interest rate on 10-year treasuries has been below its long-run average since 1998. Moreover, the rate has not been above 4% since 2008 and has not been above 3% since 2011.

Over the 61-year period from 1960 to 2021, the P/E ratio for stocks is 19.8, which is similar to the long-run average P/rent ratio. Though the long-run averages are similar, the P/E and P/rent ratios do not necessarily track one another. The average correlation coefficient between these two measures is only 0.36. Though not the topic of this paper, diversification potential between the stock market and farmland is relatively high.

Cyclically Adjusted P/Rent

Shiller (2005; 2021) uses a 10-year moving average for earnings in the P/E ratio, often labeled either P/E10 or cyclically adjusted P/E (CAPE), to remove the effect of the economic cycle on the P/E ratio. When earnings collapse in recessions, stock prices often do not fall as much as earnings, and the P/E ratios based on the low current earnings sometimes become very large (e.g., in 2009). Similarly, in good economic times P/E ratios can fall and stocks look cheap, simply because the very high current earnings are not expected to last, so stock prices do not increase as much as earnings. By using a 10-year moving average of earnings in the denominator of the P/E ratio, Shiller has smoothed out the business cycle by deflating both earnings and prices to remove the effects of inflation. Shiller also uses the P/E10 to gain insight into future rates of return. That is, if an investor buys an asset when its P/E10 is high, do subsequent returns from that investment turn out to be low, and vice versa?

The P/rent ratios reported thus far are the current year’s farmland price divided by current year cash rent. Here we are modeling our P/rent10 after Shiller’s cyclically adjusted P/E ratio. Cash rent and farmland prices are deflated, and then 10-year moving averages of real cash rent are calculated. The P/rent10 ratio is computed by dividing the real farmland price by the 10-year moving average real cash rent. A similar computation is done for operator net returns (P/NR-10).

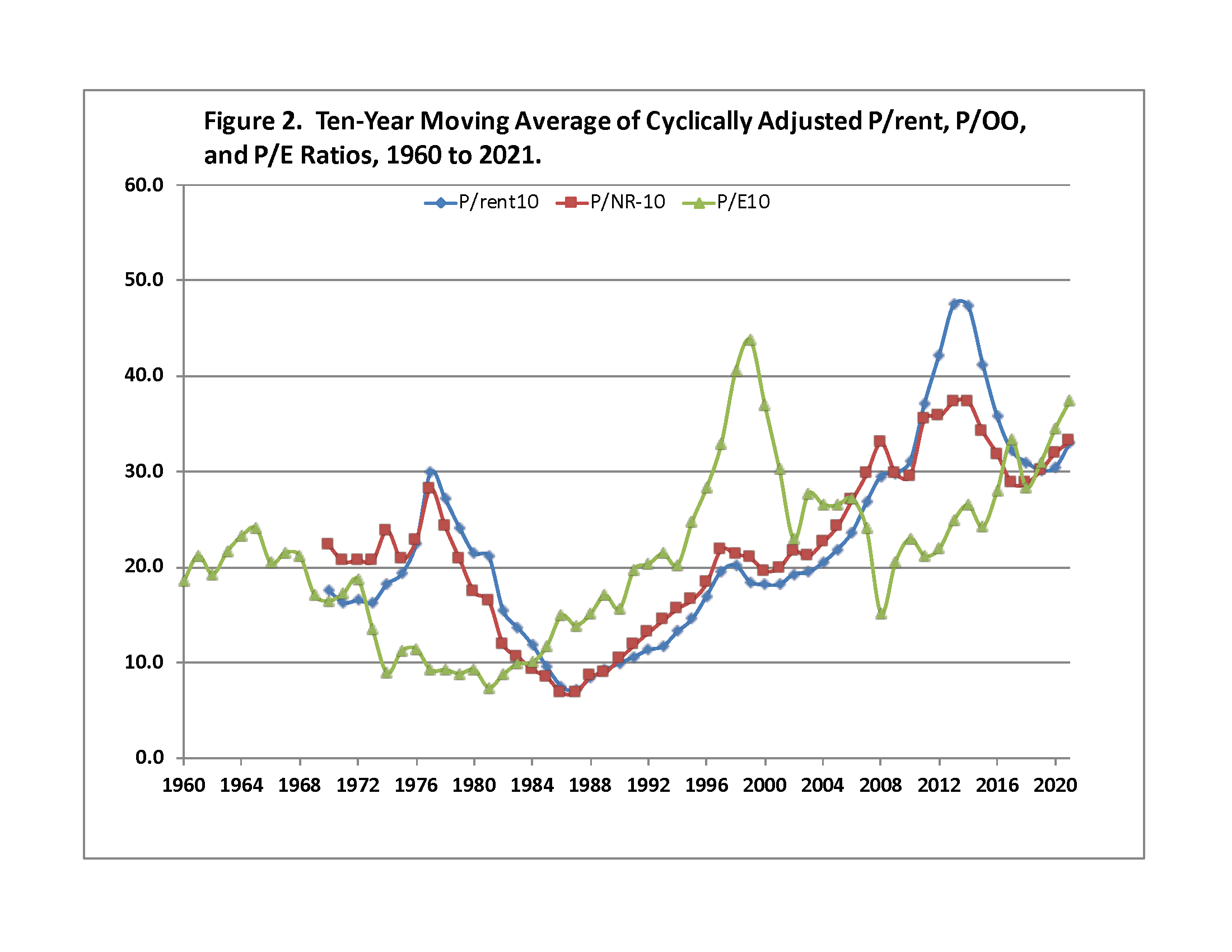

Figure 2. Ten-Year Moving Average of Cyclically Adjusted P/rent, P/OO, and P/E Ratios, 1960 to 2021.

Figure 2 shows all three of these ratios: P/rent10; P/NR-10, and Schiller’s P/E10. The P/rent10 ratio reached a peak in 2013 at 47.5. The ratio then steadily declined, reaching a level of 30.1 in 2019. The ratio increased to 30.5 in 2020 and 33.0 in 2021. The current P/rent10 ratio is still relatively high compared to the long-run average (using 1960 to 2021 data) of 22.0. Does the current P/rent10 ratio signify a bubble or is something else going on? With regard to this question, we would like to make two points. First, interest rates have been very low compared to long-run averages during the last ten years. The average rate on 10-year treasures averaged only 2.2% during the last ten years. Second, as we note below, the P/rent10 and P/NR-10 ratios appear to be in equilibrium.

The P/NR-10 ratio fell through the first half of the 1970s when real returns grew faster than land values, increased from around 20 in the mid 1970’s to 28.2 in 1977, and then fell to 6.8 in 1987. The P/NR-10 then increased steadily until it reached a peak of 37.3 in 2014. The P/OO-10 ratio has ranged from 28.7 to 34.2 since 2014. From 2015 to 2018, the P/00-10 ratio was smaller than the P/rent10 ratio, indicating that ten-year average cash rents were smaller than ten-year average operator net returns. In 2019, the P/rent10 and P/NR-10 ratios were similar. For the last two years, the P/NR-00 ratios have been slightly higher than the P/rent10 ratio. In the long-run, you would expect the two ratios to be similar. In fact, the average P/rent10 and P/OO-10 ratios for the 1960 to 2021 period were 22.0 and 21.9, respectively. The current ratios (33.0 for P/rent10 and 33.1 for P/NR-10) are very close to equilibrium.

It is evident from figure 2 that there is not a close link between the P/E10 ratio and the P/rent10 ratio. The P/E10 ratio was much higher than the P/rent ratio from 1995 to 2002. In contrast, the P/E10 ratio was quite a bit lower than the P/rent ratio from 1976 to 1981 and from 2011 to 2015.

Buy at a High Ratio: Get a Low Future Return?

Shiller also discusses the relationship between the P/E10 ratio and the annualized rate of return from holding S&P 500 stocks for long periods. In general, his results show that the higher the P/E10 ratio at the time of purchase, the lower the resulting multiple year returns, like for the next 10 or 20 years. The west central Indiana farmland and cash rent data from 1960 to 2021 are used to compute 10-year and 20-year annualized rates of return. Returns are the sum of the average of cash rent as a fraction of the farmland price each year, plus the annualized price appreciation over the holding period.

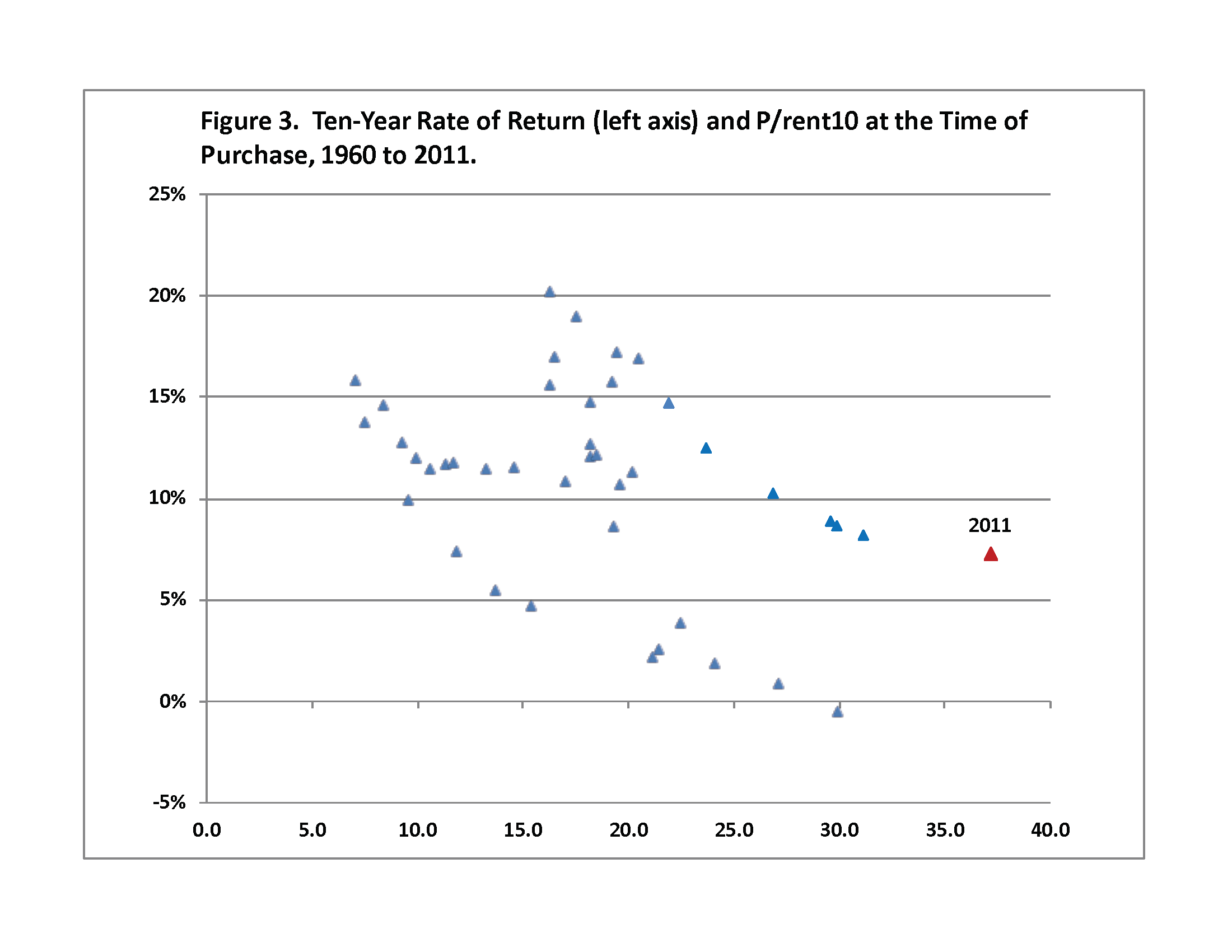

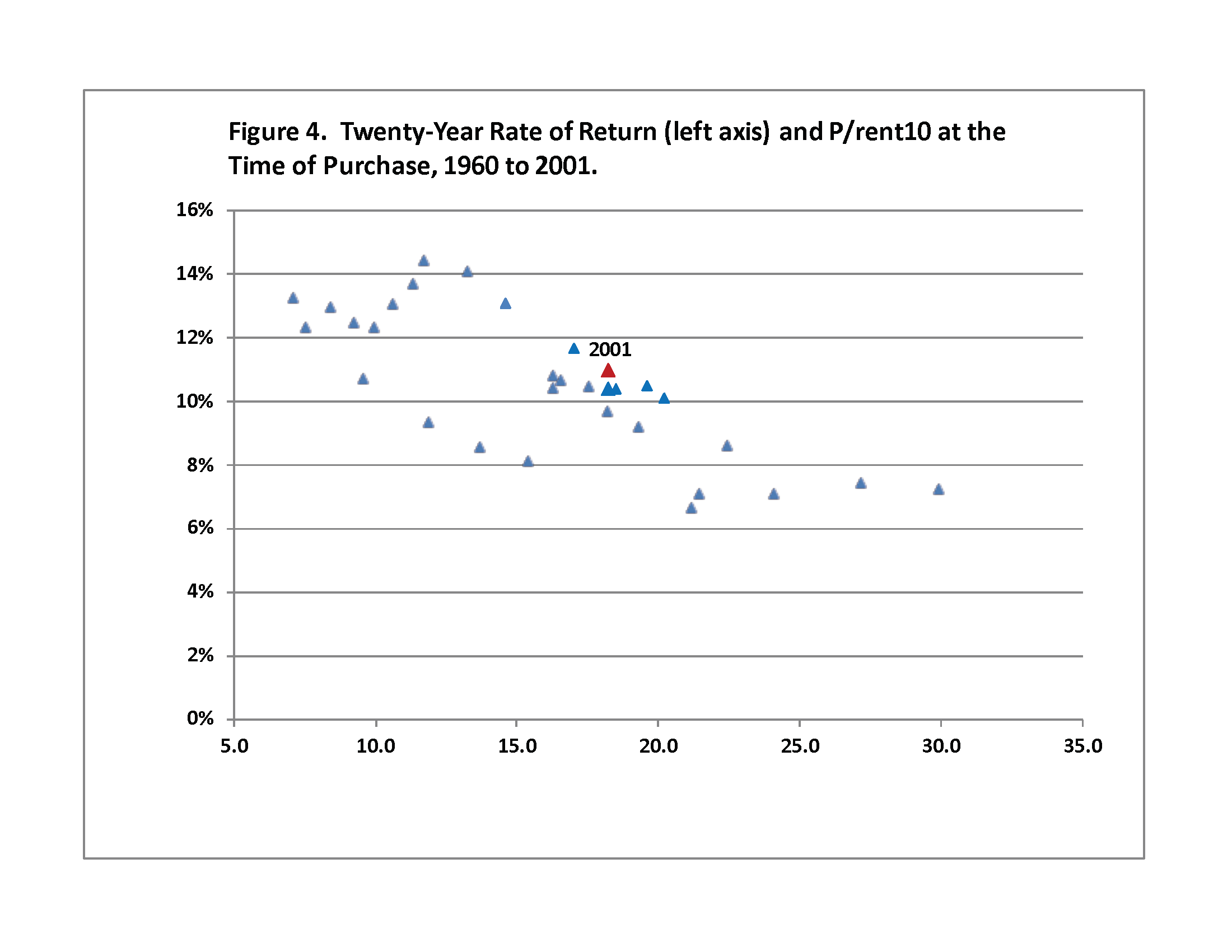

The results for farmland show a negative relationship similar to that exhibited in Shiller’s stock data. The 10-year holding period returns for farmland show a strong negative relationship (Figure 3). That is, if one purchased farmland when the P/rent10 ratio was very high, like now, they tended to have a low 10-year rate of return. Alternatively, if one purchased farmland when the P/rent10 was intermediate or low, they tended to have moderate to high 10-year returns. The 10-year returns ranged from a small negative to 20%. The 20-year holding period returns also exhibit a strong negative relationship with the P/rent10 ratio (figure 4). The 20-year holding returns range from 6 to 14%.

Figure 3. Ten-Year Rate of Return (left axis) and P/rent10 at the Time of Purchase, 1960 to 2011.

As noted above, figure 3 presents the ten-year rate of return for farmland and the P/rent10 ratio for land purchased in west central Indiana from 1960 to 2011. The P/rent10 ratio in 2011 (i.e., 37.2) was higher than any ratio experienced since 1960. Despite this fact, the ten-year rate of return for farmland purchased in 2011 was still 7.3%. The P/rent10 ratios for land purchased in 2012 through 2015 are literally off the chart (horizontal axis of Figure 3). P/rent10 ratios for this time period range from 41.2 in 2015 to 47.5 in 2013. From 2016 to 2021, the P/rent10 ratios range from 30 to 36. Will rates of return for land purchased since 2012 stay above 7%? The answer to this question depends on what happens to operator net returns and interest rates. If operator net returns remain strong and interest rates stay low, the answer to the question is probably yes.

The 20-year rate of return for land purchased in 2001 is 11.0 percent, which is in the middle of the range of 20-year rates of return illustrated in figure 4. It will be interesting to see if the 20-year rate of return declines as the P/rent10 ratio increases in the next few years. For land purchased in 2001 the P/rent10 is 18.2. In the next five years, this rate will increase to approximately 24, and then increase dramatically for land purchased in 2007 on.

Figure 4. Twenty-Year Rate of Return (left axis) and P/rent10 at the Time of Purchase, 1960 to 2001.

Final Comments

Our analysis indicates that the P/rent ratio (price per acre divided by cash rent per acre) is substantially higher than historical values. In order to maintain the current high farmland values, cash rents would have to remain relatively high, and interest rates would also have to remain very low. Most agricultural economists expect crop returns to remain relatively strong in the next couple of years, mitigating downward pressure on cash rents, and for interest rates to remain similar to current levels in coming years, providing support for the current P/rent ratio.

We demonstrated that farmland values have tended to have a cyclical component in which farmland values move too high relative to the underlying fundamentals and then over time move too low relative to fundamentals. We use a cyclically adjusted P/rent ratio to show that a very high P/rent ratio, as we have now, tends to be associated with low subsequent returns. Simply stated this means that the historical relationships show that those who bought farmland when the P/rent ratio was high tended to have low subsequent returns. On the other hand, those who bought farmland when the P/rent ratio was intermediate or low, tended to have intermediate or high subsequent returns. The current record high P/rent ratio could be a warning to current farmland buyers that their odds of favorable returns on these purchases are probably not high.

Our reading from examining 61 years of history is that the current relationship between farmland prices and cash rents suggests that farmland prices are elevated. If we are correct, this means that those purchasing farmland at current prices may experience “buyer’s remorse” in coming years. But having said this, there remain some possible situations in which farmland values could be maintained or even increase. Positive influences on land include low interest rates, the relatively small percent of land currently on the market, the attractiveness of farmland to pension fund managers, and the fact that land is a good hedge against inflation.

References

Kuethe, T. 2021. “Indiana Farmland Prices Hit New Record High in 2021.” Purdue Agricultural Economics Report, Purdue University, July 2020, pages 1-8.

Shiller, R.J. 2005. Irrational Exuberance, Second Edition. New York: Crown Business.

Shiller, R.J. 2021. S&P 500 P/E Ratio. www.multpl.com, accessed July 19, 2021.