Graduate Ag Research Spotlight: Shelby Gruss

SHELBY GRUSS

“High-throughput phenotyping is a huge field with new opportunities, and just to be part of it is exciting. You get to see new things and do things that people haven’t done before and that could help someone in the future.”

— Shelby Gruss, PhD student, Agronomy

THE STUDENT

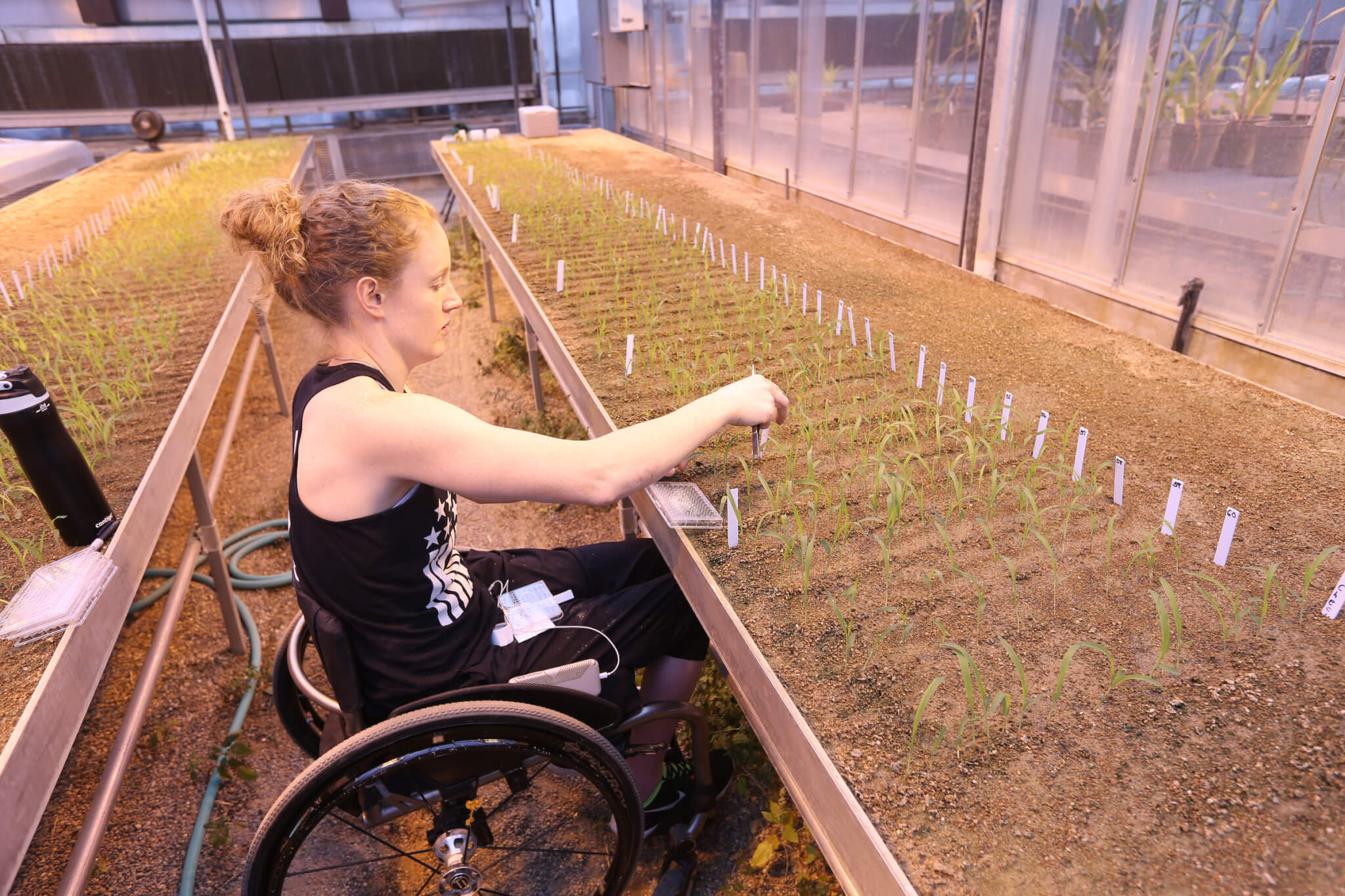

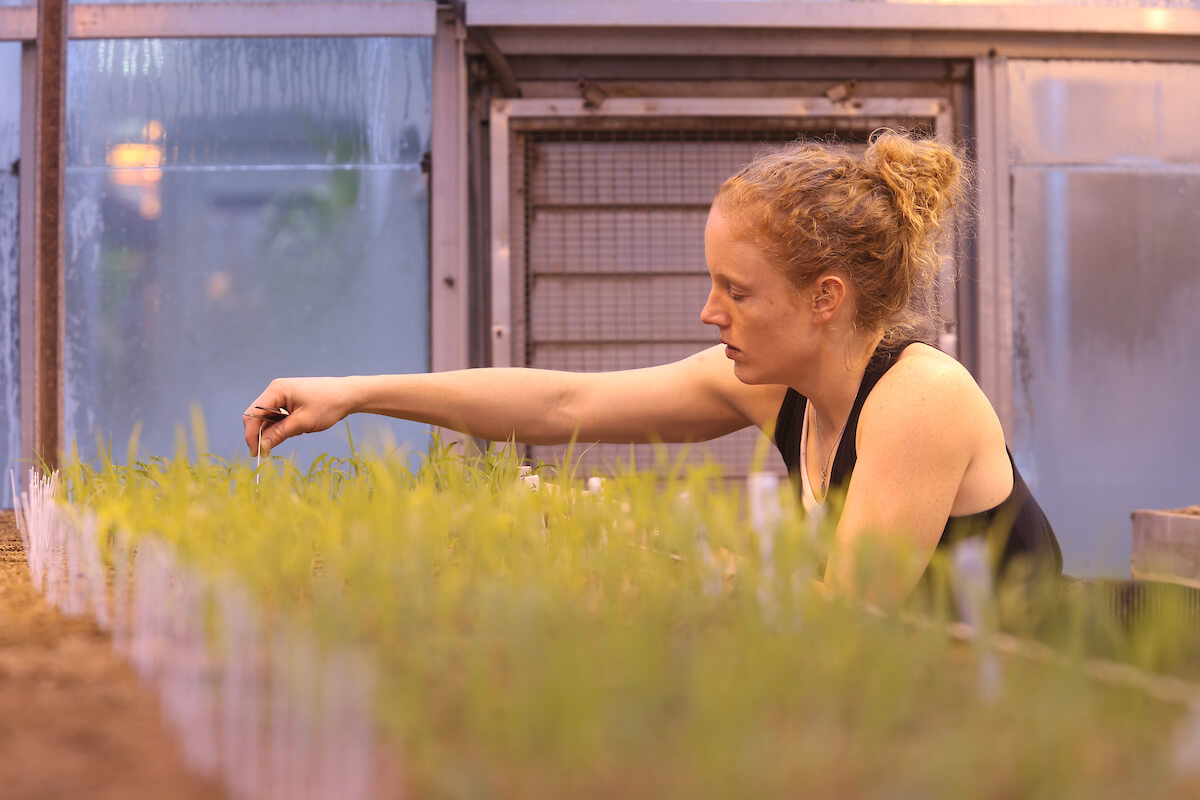

Self-described “science person” Shelby Gruss decided to apply her specific interest in genetics to agriculture. From her family’s small farm in Ossian, Indiana, she spent two years at Indiana-University-Purdue University Fort Wayne — the universities have since separated — before transferring to the University of Illinois to study biotechnology and molecular biology. She then earned a master’s degree at Illinois in an agricultural production program that combined science with business. Gruss was leaning toward doctoral study in Florida when a friend in agribusiness introduced her to some of his Purdue contacts. Those interactions led to her starting her PhD program in Agronomy in January 2018 under the guidance of Mitch Tuinstra, professor of plant breeding and genetics and Wickersham Chair of Excellence in Agricultural Research. Gruss has used a wheelchair since a snowboarding accident her senior year of high school left her paralyzed from the waist down. Adaptations such as wider row spacing in the greenhouse and field enable her to focus on her research instead of her disability. “In my lab, Andy our lab tech has been great about adjusting anything that needs to be adjusted,” she says. “Everybody been proactive about helping me be a success here.”

THE RESEARCH

Gruss works with sorghum, a crop grown around the world. Compared to other forage crops, sorghum is sturdier, tolerates drought better and requires less nutrients to produce high yields. However, it contains a compound called dhurrin that breaks down and releases a toxic gas, especially during the early stages of the plant’s life, she explains: “Sorghum is an important forage crop, but this compound deters farmers from using it.” Gruss is studying selected traits in new lines of dhurrin-free sorghum to compare its potential value and productivity to dhurrin-producing plants as well as its performance in the production setting. “I want to be able to do a communications piece at the end to see the viability of this becoming mass-produced crop,” she adds.

CEPF

Gruss is preparing to conduct her first experiment with 90 or so plants in Purdue’s Controlled Environment Phenotyping Facility. The CEPF, she says, “gives me the ability to look at exactly what I want to look at.” Its specific conditions, consistent imaging and availability of rapid data analysis will help Gruss take her research to the field this summer.

FUTURE PLANS

Both sorghum’s prospects and her own are exciting, Gruss says. Although she remains open to various career options, she is interested in bridging science and business by articulating research results in ways that industry can apply. Gruss understands teamwork: She played for the University of Illinois’ wheelchair basketball league and served as captain of Team USA at the International Wheelchair Basketball Federation’s World Championship. In addition to morning workouts at the Co-Rec, Grussenjoys her dog Sadie, if not the bernedoodle’s enthusiasm for chewing books (so far, none in agronomy.)