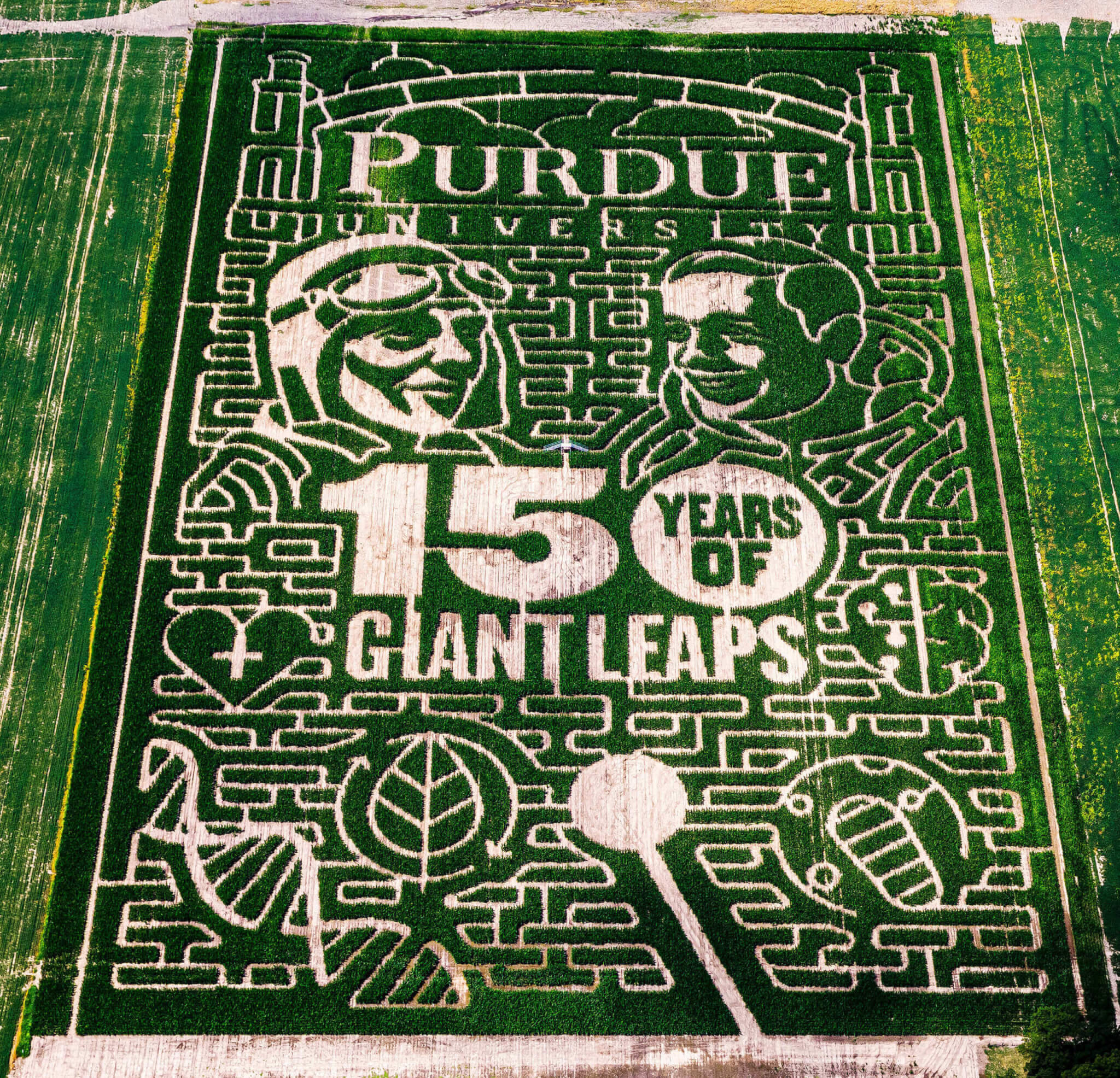

“You don’t want a corn maze to be too simple, but you also don’t want it to take too long and have people in there panicking,” Dan Quinn, assistant professor of agronomy and Extension corn specialist, said. “There’s a lot of thought that goes into making one.”

Labyrinths have an ancient history, imbued with mysticism and mythology. The earliest known maze, which dates back to the fifth century, was designed as a form of spiritual meditation for visitors to the pharaoh Amenemhat III’s funeral temple. Many different faiths hold the belief that walking labyrinths serves as a form of prayer and encourages spiritual transformation. Other labyrinths found throughout Europe were used as means of religious meditation, ritual and entertainment. They could often be found on the grounds of monasteries or royal estates.

Today, many Americans faithfully visit corn mazes as part of their fall fun, a distinctly American pastime and squarely in the entertainment category. They are also a recent phenomenon. The first known corn maze created for entertainment dates back to 1993, located in Annville, Pennsylvania, and was designed to drive area tourism.

Maze mapping technology has come a long way since the fifth century, of course, as well as since the early 90s.

Quinn said farmers traditionally grew a standard field of corn in a square or rectangular shape and then walked the maze, staking out the pattern as they went. GPS technology, however, revolutionized this process, making it possible to digitally render the maze and plot it out precisely.

“Even with GPS, it’s a pretty labor-intensive process,” Quinn added. “You’re still walking the pattern several times and pinpointing where things need to be cut.”

The corn for mazes is cut down when the growing point is above the soil surface, that’s a certain height above the ground where if the plant is killed it won’t resurrect. Farmers mow the intended path and then go over the dirt with a rototiller to make it walkable.

Like regular corn harvested for grain, corn intended for mazes and agritourism is still susceptible to the challenges of the growing season.

“You need to have a good idea of where in your maze there may be areas prone to wind or storm damage at the time you design the maze,” Quinn advised. “When you’re cutting intricate designs, if there has been a drought or significant disease, the stalks are more prone to fall over. I’ve seen farmers often redesign their mazes because of this issue.”

Even though the main purpose of a corn maze is to attract people seeking autumn thrills, Quinn said, farmers still like to keep the crop healthy. If people are looking at the corn, they want it to look good, and, when the corn maze season ends, they will still harvest the field for any remaining grain.

“There’s no reason that corn isn’t usable,” he continued. “If the crop can be used to attract people to the farm and to sell later, usually for animal feed, that’s a win-win.”

Animal sciences student publishes fantasy but has real-world ambition

“When it comes to writing about animals I definitely use my knowledge from school, but my knowledge about elves and fantasy doesn’t help me much with school,” Sara Tonissen, a senior in animal sciences, laughed.

Read Full Story >>>Purdue Agriculture Halloween Activity Pages

Are you looking for Halloween activities for children? Here’s a festive page with a corn maze, “carving” pumpkins and connect-the-dots. (Bonus: you can teach your little one a fun fact about bats!)

Read Full Story >>>Indiana is one of the country’s top pumpkin growers. Also, another name for Jack o’ Lantern is Hinkypunk.

By Emma Ea Ambrose Hinkypunks. Hobby lanterns. Fairy lights. Corpse candles. Fool’s fire. All of these whimsical names, which originated in Ireland, once referred to the other-worldly lights of evil spirits that would appear in the night above bogs and swamplands. Centuries before science would explain away these ethereal flares as the ignition of decomposing…

Read Full Story >>>