America’s Farmers: Environmental Stewards or Ravagers of the Land

August 16, 1992

PAER-1992-16

Stephen B. Lovejoy, Professor and Coordinator of the Center for Alternative Agricultural Systems

American agriculture is increasingly seen as a major cause of water quality problems. Farm magazines carry stories about water quality problems caused by the production of food and fiber, and the general public is treated to articles and documentaries on the “agricultural” problem. Calls for agricultural production which is more environmentally benign are rampant. These range from calls for tillage changes, to more radical calls to forego all agricultural chemicals and farm organically, or even to return to our days as hunters and gathers. As concern for environmental resources has grown, environmentalists have called for more regulatory control of the production of food and fiber to protect valuable natural resources, including water quality.

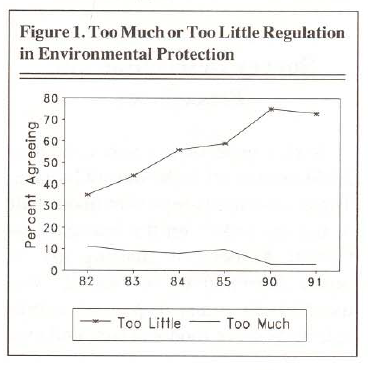

As illustrated by Figure 1, Americans have increasingly been suggesting that we have too few regulations in the area of environmental protection. These attitudes toward regulation for environmental protection were increasing even through the early 1980s when the government, with popular support, was deregulating various sectors of the economy.

Recently, there have been suggestions to legislate this control through the Clean Water Act, especially Section 319, which will be reauthorized by Congress. Some environmentalists suggest that America’s farmers have had a free ride long enough; other American businesses have been reducing their degradation of water resources while farmers have been conducting business as usual. The logic seems to be that farmers must be coerced into appropriate environmental behavior just as society had to force industries into protecting the environment.

If we examine the behavior of nonfarm businesses, utilizing our economic tools, the logic seems to be overwhelming. Businesses are concerned with the bottom line, and externalities like water pollution are imposed upon society without a charge. When the businesses are forced to internalize some of the costs of pollution, they behave more appropriately. When we look at point sources of water pollution, this logic seems impeccable. Industries did little or nothing to reduce their discharges until forced to do so by regulation with the threat of penalty. After two decades of such regulation of point sources of pollution, we have made significant progress in providing Americans with cleaner water.

Now however, many observers suggest that in order to meet our water quality goals, originally established in 1972 as fishable and swimmable, we must regulate nonpoint sources of pollution, especially agriculture. The logic is that we have ignored the role of agricultural producers in water quality and we have arrived at the point where controls on industry can only be made at large unit costs. This logic also suggests that farmers have not sacrificed and now is the time. The assumption in most of this is that farmers have not been performing their role as environmental stewards – in fact, they have been ravagers of our resources much like the non-farm businesses.

But what do we know about water pollution from agricultural operations? According to USDA publications on the Resource Conservation Act (RCA) assessments, between 1977 and 1982 American agriculture increased the number of cropland acres 2% while at the same time reducing the tons of sheet and rill erosion from cropland by over 1% [1,2].

The changes in erosion since 1982 have been much more dramatic. In the 1980s, farmers made significant changes in their cropland production patterns, including less tillage and more rotations. In addition, government programs made other changes attractive, e.g., Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) and Conservation Compliance (CC). Between 1982 and J 990, our research estimates that the erosion was greatly reduced and loadings of sediment into our waters was reduced by 29% [3]. In addition, the phosphorus and nitrogen attached to those soil particles was also reduced by 29%. These estimates include the CRP acreage but not the impact of changes resulting from conservation compliance plans.

By 1995, all conservation compliance plans should be implemented and gross erosion will be further reduced. Our estimate of the impact on the loading of sediment into our nation’s waterbodies by 1995 is a reduction of 49% from 1982 levels; similar percentage reductions in nitrogen and phosphorus would be expected [3].

Figure 1. Too Much or Too Little Regulation in Environmental Protection

The question becomes how much further should agriculture go, and where is the cheapest alternative for achieving increased water quality – controls on agriculture or additional controls on industries?

Agriculture has made extraordinary progress without requiring a great deal of regulatory control – certainly agriculture has made more progress without regulation than other industries.

While it is uncertain how much additional progress the agricultural sector can make voluntarily, that should be an empirical issue, not an assumption that America’s farmers have done nothing about meeting society’s water quality goals.

References

- 1980. Soil, Water and Related Resources in the United States: Analysis of Resource Trends. RCA.

- 1989. The Second RCA Appraisal.

- Lovejoy, Stephen B. Interim Report 3 from Purdue University to USDA, Soil Conservation Service. 1991.