Antitrust Law and the Food and Agricultural Cartels of the 1990s

February 13, 2003

PAER-2003-3

Jeff Zimmerman, Research Assistant and John M. Connor, Professor

A cartel is an organization dedicated to fixing prices. Cartels have been a feature of business conduct for over 125 years, but in the past decade unprecedented global growth in cartel activity has been observed in the food and agricultural industries. This growth has been countered in part by heightened legal sanctions and by improved prosecutorial techniques adopted by the U.S. Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Antitrust Division and European Commission’s Directorate General for Competition (DG-IV), among others.

The U.S. Department of Justice successfully prosecuted scores of international price-fixing cartels in the late 1940’s. However, for nearly 50 years few international cartels were discovered or prosecuted. After 1950, the DOJ prosecuted only 3 or 4 international cartels out of a total of 20 to 60 annual cases. During 1988-1992, more than 20 global cartels were formed by manufacturers in North America, Europe, and Asia, mostly in the food/feed ingredient industries.

The pattern of enforcement changed considerably seven years ago. The lysine cartel convictions of 1996 initiated a series of successful cartel prosecutions by the DOJ throughout the late 1990s. The DOJ has improved its record of convictions through heightened fine structures and more extensive cooperation with the FBI and foreign antitrust agencies and by treating cartel episodes more like serious organized crime. Antitrust agencies abroad have increasingly imitated the DOJ’s successful anticartel policies.

The ADM Case – a Milestone in International Price-Fixing Cartels

The 1996 lysine cartel conviction was the result of an FBI undercover operation that began in 1992 and ended June 1995 with raids on the headquarters of ADM and four

co-conspirators (Japanese and Korean companies). The aftermath of the successful prosecution resulted in a $70 million dollar U.S. corporate fine imposed on ADM, with the other co-conspirators paying $23 million more. Personal convictions included three Asian executives pleading guilty and paying small fines in 1996. In 1998, three ADM executives were found guilty at a trial in Chicago, paid $1,050,000 in fines, and were made to serve 99 months in prison collectively.

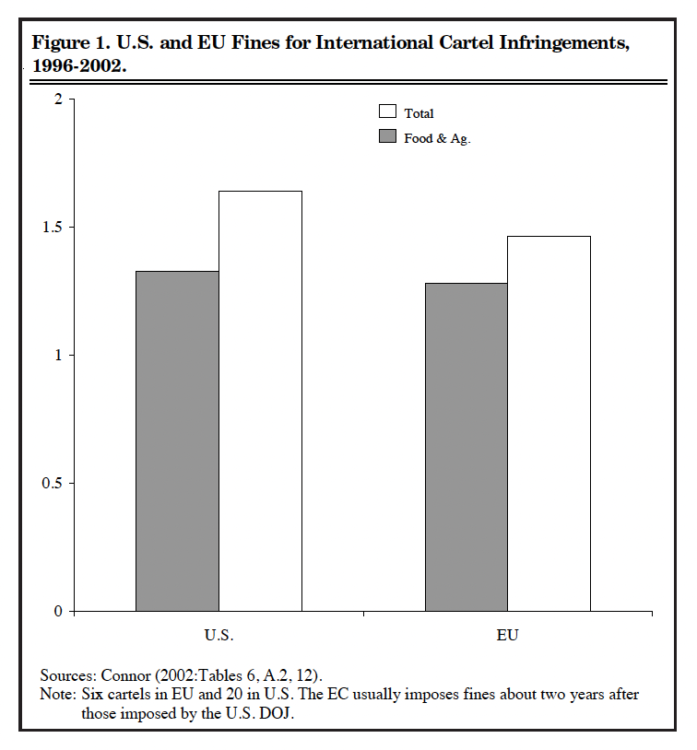

From 1997 to 2001, DOJ corporate price-fixing fines amounted to more than $2 billion dollars, compared to an average of $27 million per year between 1986 and 1996. Unlike the pre-1997 price fixing cases, 90 percent of the corporate fines imposed have been on global cartels, and, of these, 85 percent were in the food and agriculture sectors (Figure 1). These global cartels differ from those of the past in the global scope of their price setting, scale of operation, inclusion of non-European members, and greater durability.

Figure 1. U.S. and EU Fines for International Cartel Infringements, 1996-2002.

Successful Anticartel Techniques

The federal law designed to combat cartels is the 1890 Sherman Act. In addition to the criminal powers given to the DOJ to fine companies and cartel managers, the Act allows for private suits against cartels. The outcome of a successful private suit is treble damages (i.e., settlements equal to three times the victims’ economic losses). The purpose of the treble damages is to compensate buyers who paid artificially high prices to the cartel members and

to deter firms from forming cartels.

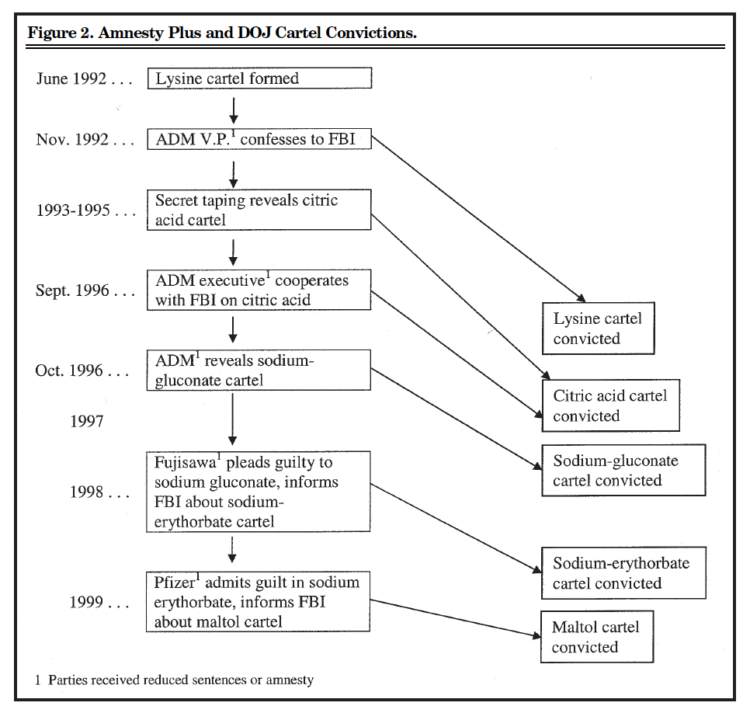

The U.S. has continued implementing innovative prosecution methods for corporate price-fixing, including the 1993 antitrust Leniency Program that guarantees automatic amnesty, that is, a 100 percent discount on its fine specified by the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines, for the first to confess (cartel ringleaders exempted). Even the second and third companies to confess and cooperate usually receive substantial discounts. This program creates incentives for firms to defect from the cartel and often results in a “race to be first” to confess to the world’s eight antitrust agencies with these policies. The DOJ’s recent “Amnesty Plus” program rewards target companies if they inform the DOJ about collusive activity in a market not yet being investigated. The lysine cartel discovery ultimately led to the conviction of four other global cartels in the food and feed industry through the amnesty plus program (Figure 2).

Fines have been increased significantly in the last decade or two. In 1990, Congress increased maximum penalties for corporations up to nine times a cartel’s illegal monopoly profits; this compares to at most $50,000 in 1974. In addition, individual penalties for cartel executives increased to $25 million and 36 months in prison from the respective 1974 levels of $50,000 and 12 months.

Figure 2. Amnesty Plus and DOJ Cartel Convictions

Prosecuting Global Cartels – a Growth Industry

Since 1996, the U.S. DOJ has convicted hundreds of companies and persons that operated 40 global cartels. The total sales during the price-fixing period of these 40 discovered global cartels was a startling $76 billion, of which $20 billion (26%) was in the United States. On average, prices were driven up by about 25 percent during these conspiracies.

Before 1997, less than 1 percent of all firms indicted for price fixing were foreign. Since then more than 50 percent have been foreign multinationals; in 2001 70 percent were foreign. Interestingly, the U.S. justice system has begun to function as an international prosecuting institution. The first foreign executive ever convicted for U.S. price fixing was in 1993. Today, 12 executives from foreign countries have been so convicted, some of whom with residence abroad traveled to the U.S. to be imprisoned for price-fixing. The United States is virtually the only jurisdiction in the world that regularly imprisons price fixers.

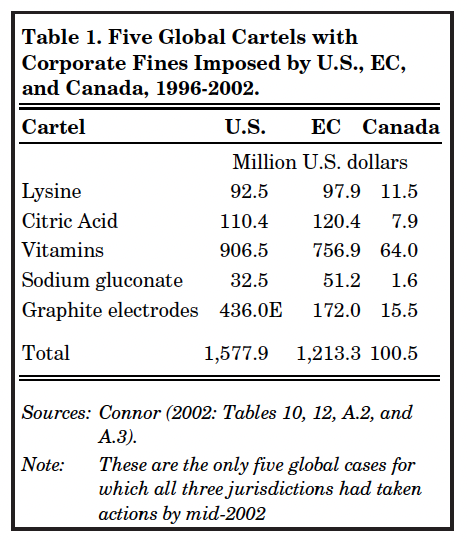

Convergence in cartel enforcement worldwide has aided in the partial recovery of global market damages and serves to reduce future occurrences. Indeed, E.U. and Canada corporate fines imposed an additional 98 and 11.5 million U.S. dollars, respectively, to lysine cartel participants (Table 1). International treaties and protocols have made joint raids and information sharing possible.

Nevertheless, there are still substantial differences in anticartel enforcement around the world. In the U.S. and Canada, price-fixing is a per se offense, meaning that no evidence on economic impact need be presented to prove allegations. However, the EU treats antitrust violations solely as a civil infraction by a business entity. Thus, individual conspirators are not personally liable for monetary penalties or imprisonment. Moreover, outside the U.S. and Canada, private antitrust suits are either not possible or ineffective.

Table 1. Five Global Cartels with Corporate Fines Imposed by U.S., EC, and Canada, 1996-2002.

Can the Law Deter Cartels in the Future?

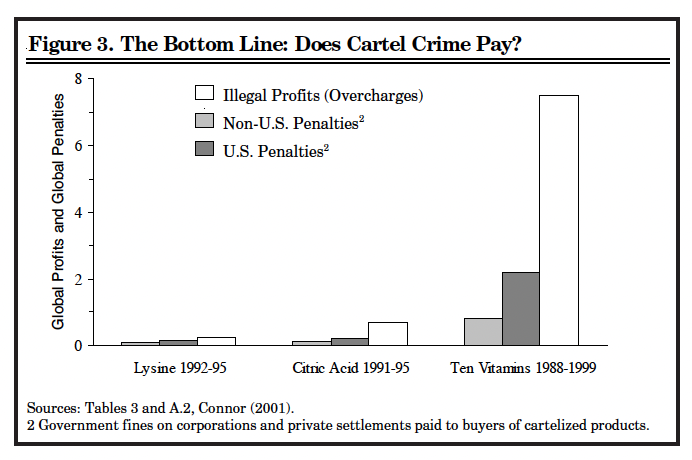

Despite the heightened fines and increased probability of detection, there are many reasons to believe that cartels continue to operate in secret. Simply put, deterrence will only be achieved if companies perceive that the expected financial costs of collusion exceed the expected additional profits. To date, no global cartels have had global financial penalties exceed

global financial costs, except lysine perhaps (Figure 3).

Given the lucrative nature of cartel crime, recidivism is very prevalent among participants. ADM, for example, has definitely participated in three price-fixing schemes (lysine, citric acid, and sodium gluconate) and probably joined six others (corn sweeteners, carbon dioxide gas, monosodium glutamate, nucleotides, methionine, and wine alcohol). A dozen other firms are repeat offenders.

Evidence shows that most cartelists are fairly accurate at predicting additional profits associated with price-fixing schemes; however, their durability is often unknown in advance. With the historical probability of discovery at 10-20 percent and chances of conviction upon discovery at 50-75 percent, and with most cartel profits being made outside the United States these days, it is eminently rational for would-be cartelists to assume the risk of legal punishment. Deterrence measures are difficult to assess; however, given these rational expectations, to ensure absolute deterrence the total financial sanctions should be at least 20 times the expected U.S. cartel profits (overcharges) and 60 times the U.S. overcharges in extreme cases.

To date, no global cartels have had to pay more than two or three times what they gained in illegal profits. Despite the prosecutorial successes of the past five years, on average, cartel crime still pays.

Figure 3. The Bottom Line: Does Cartel Crime Pay?

Further Reading

John M. Connor, Global Price Fixing: “Our Customers Are The Enemy”. Boston: Kluwer Academic (2001)

University (August 2002), 56 pages. [www.agecon.lib.umn.edu/pu.html]. John M. Connor, “The Food and Agricultural Global Cartels of the 1990s”, SP 02-04.W. Lafayette, IN: Purdue