Are Exports a Dependable Base for Farm Prosperity?

June 13, 2002

PAER-2002-4

Otto Doering, Professor; Michael Boehlje, Professor; and Neil Meyer, Extension Professor, Dept. of Ag Econ. and Rural Sociology, University of Idaho

Lester Thurow says “what sounds sensible (export more) when heard separately in each country becomes nonsense when aggregated around the world. No one can have more net exports unless someone else has more net imports.”

Thurow, Lester. 1999. Building Wealth: The New Rules for Individuals, Companies and Nations in a Knowledge-Based Economy. Harper Collins, New York, p. 71.

Background

We have a strong relationship between exports and farm prosperity in the United States. From the early 1900s to the early 1920s, increasing prices and export volumes made farming unusually prosperous and boosted land values. During World War II and its aftermath, another boom in prices and exports was experienced. A third boom occurred in the 1970s, which peaked in 1981. All the prosperous periods were the result of political decisions or crop failures.

If we calculated the full cost of exports, including government support to farmers, transportation subsidies, damage to the environment, etc., sometimes we ended up exporting commodities below our full internal costs of production. (Schmitz, et al.)

High commodity prices encourage all farmers to produce more. The high prices in 1995-97 certainly helped bring about our current oversupply of commodities. We know that increasing U.S. commodity prices through high loan rates in the 1970s increased the prices for farmers beyond our borders. We changed our policies in 1985 to avoid this by moving to lower loan rates and depending more on deficiency payments for our farmers, basing this on a target price set well above the loan rate.

What we see historically is long periods of moderate or low prices punctuated with shortages and high prices and export demand. Despite policies to boost grain exports, volume has been mostly flat since the 1980s. High prices from export booms have been rare (such as during the teens and during the 1970s).

Why Do We See What We See Today?

- Agricultural commodity markets are mature. In a mature industry, technical changes tend to increase supply faster than demand. Agriculture commodities have an inelastic demand; therefore, supply increases cause larger percentage price decreases. To increase market share, one has to sell at lower prices. High prices encourage competitors to increase production. In the case of grains, a long period of low prices might discourage high-cost producers and allow the U.S. to increase export share. The cost for this would be some producers going out of business or government transfers to farmers allowing them to maintain their incomes. Today’s farm program is effectively doing this.

- The export boom of the 1970s had some important agricultural drivers: (1) Bad weather around the world and (2) the corn blight in the U.S. The critical non-agricultural drivers were:

- The decision of the Soviet Union and other Communist states to import grains,

- (b) freeing of the dollar from fixed exchange rates made our exports less expensive in terms of other currencies, and (c) recycling of petro-dollars, which resulted in international banks making vast loans to countries (in South America and Eastern Europe) that they used to buy grains.

- Food is a strategic good. Politically, many countries have social policies to slow out-migration from agriculture and to encourage the maintenance of the present investment stock in agriculture.

- Free markets in commodities and inputs, may not make for high prices and volumes. Prices and volumes would likely be different under free trade from where they would be otherwise, but farmers might not be more prosperous. Land values would be driven lower in those countries that previously subsidized their agriculture and their exports. This would hurt current owners. Free trade would not necessarily end the boom-and-bust cycles brought about when high international prices encourage everyone to invest, overshoot, and produce more. We continue to have the capacity in the U.S. to produce more than we need. As long as other world producers are in the same over-capacity position, or want to be self-sufficient, a U.S. free trade position will not necessarily bring prosperity to U.S. farmers.

Future Trends That Are Important to Us

- The mobility of technology and the increasing speed of its development change the outlook for our exports. Lowered variable costs will become the driver of production through enhanced technology. International markets for technology will be opened, which profoundly effects the location of grain production.

- With a slowdown in population and income growth combined with productivity and acreage increases, demand for grains is unlikely to catch up with the current stockpiles unless there is abnormal weather.

- Capital for investment in agricultural production and processing is very mobile. European and U.S. livestock, poultry, and potato processing companies are investing in production capacity in Latin America, Canada, and Eastern Europe. The key here is raw materials will be obtained near processing facilities.

Where Does This Leave Us?

In terms of our current situation of world oversupply, demand is not likely to grow quickly enough to take care of the problem. There has to be:

- new forms of demand growth,

- weather or policy-driven supply control, or

- acceptance of a prolonged period of low prices. High prices stimulate oversupply because once demand shortages are met, the investment and production continue as long as variable costs are covered. If price is to be the mechanism to reduce supply, it then takes a long period of low prices to reduce world supply. Meanwhile, income support policies keep land in production.

Supply adjustment can come from reduced acreage or from reduced yields. Reduced yields will occur with reduced inputs (land, fertilizer, technology) or bad weather. Farmers don’t take land out of production as long as they can cover variable costs.

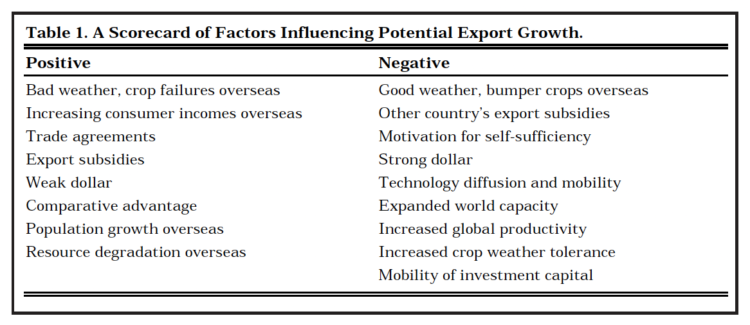

A variety of factors involved in determining export growth are listed in Table 1. An assessment of these factors does not indicate export growth as a foregone conclusion even with more open trading rules.

The strongest potential growth avenue for grains may be processing, where most of the demand growth has occurred over the past 20 years. This goes beyond taxpayer subsidized ethanol production and price protected fructose production to such things as biochemicals and plastics. However, this usually requires price stability at moderate levels for the raw materials.

Table 1. A Scorecard of Factors Influencing Potential Export Growth.

Summary

The long-run experience in creating agricultural prosperity through export growth is not very good. Technology moves across borders easily and rapidly. Price spikes encourage excess investment, which results in excess production. It can take many years for invested production capital to depreciate and reduce overall supply.

Prosperity from agriculture and food product production will come to those adding value to basic commodities supplying consumer desires and finding new uses for commodities. The largest returns will likely be to those meeting consumer demands by adding value and capturing market niches. For example, production agriculture needs to look at things such as how healthy foods reduce heart disease, cancer, and other diseases. Producers must find ways to capture added value rather than produce more commodities.

Reference

Schmitz, A., D. Sigurdson, and O. Doering, “Domestic Farm Policy and the Gains From Trade.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 68, No. 4, Nov. 1986.