China: Emerging Opportunity for the U.S. and Indiana Duck Industry

April 13, 2015

PAER-2015-2

Rachel Carnegie and H. Holly Wang, Professor of Agricultural Economics

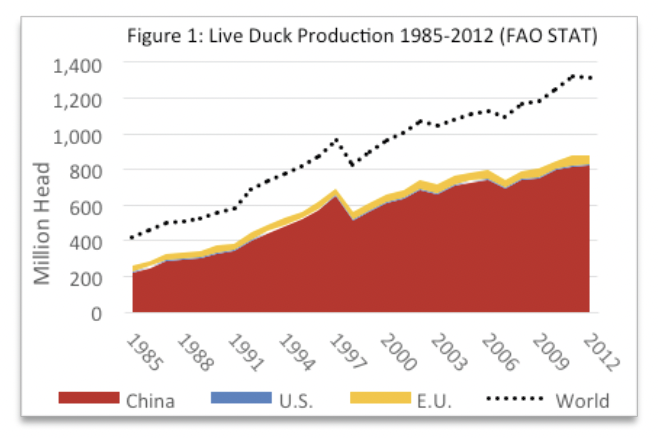

Duck is a small specialty meat in the U.S., however, it has an enormous market in Asia. In the last three decades, the world duck production expanded 3.1 times, from about 400 million head in 1985 to 1.3 billion head in 2012 (Figure 1). China dominates world duck consumption with 3 million tons produced domestically plus a net import of 13.2 thousand tons in 2011. U.S. duck production is barely visible in Figure 1. The quantity and quality demanded in China has risen with disposable incomes, with urban population growth, with internal food safety scandals, and with changing consumer tastes. It is in this rapidly-evolving yet huge market that provides an emerging opportunity for the U.S. duck industry and the corn and soybean producers who would provide their feed.

Figure 1. Live Duck Production 1985-2012 (FAO STAT)

Traditionally, the duck industry in China produced birds with heterogeneous qualities for purchasers who preferred strong-tasting, domestically-produced, and often older-age ducks. Today, a new market for premium-quality ducks has emerged, particularly amongst affluent, urban, quality-conscious buyers. These buyers increasingly rely on branding, quality guarantees, safety certification, and country of origin labeling to determine product quality and safety.

The motivating factors for this outgrowth of traditional duck demand can be traced to demographic, sociocultural, economic, and dietary changes taking place in China. Demographic transition includes changes in family structure, urban population growth, and education levels, as well as the opening of Chinese cities to global commerce which brings new cultural influences. Additionally, increases in consumer disposable incomes have increased food consumption volumes and resulted in stronger desires for improved food quality (Gale & Huang, 2007). As a result, major deviations away from traditional Chinese diets are taking place including increases in meat consumption, particularly poultry and beef, and increased dinning out. Thus it is in the food service industry that many high-quality meat products may be sold at a premium.

The EU duck industry has already capitalized on this new demand opportunity and begun marketing their breeds and products in the Chinese market. U.S. firms are equally eager to enter the Chinese market and well positioned to do so. Two main strengths of the U.S. duck industry are: (1), its advanced production technology and biotechnology in developing breeds with particularly desirable features such as a high muscle meat ratio, low feed conversions, and disease resistance, and (2), its reputation in food safety and quality control. Three main challenges to the U.S. duck industry are:

(1) The limited growth opportunities in the domestic specialty meat market

(2) The Chinese traditional preference for domestic products over imported ones

(3) The lack of information in the U.S. about the Chinese duck market and a lack of understanding of Chinese consumer segments and their preferences.

To address the last two concerns we surveyed restaurant consumers and managers. The surveys were conducted during the summer of 2013 in Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, and Guangzhou, representing four different geographic and cultural regions of China. One manager and five consumers from randomly selected restaurants were interviewed by trained enumerators. Restaurants ranged from large luxury restaurants with many private dining rooms to small “mom-and-pop” restaurants with scarcely ten tables.

Consumers are Different

Demographic features of consumers such as gender, age, education, household size, annual household income, income changes, and migration are often linked with particular behavioral patterns. In addition, each city (region) has unique local traditions and characteristics that impact behavior patterns.

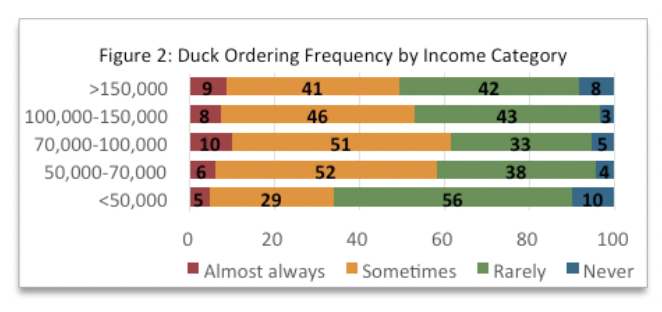

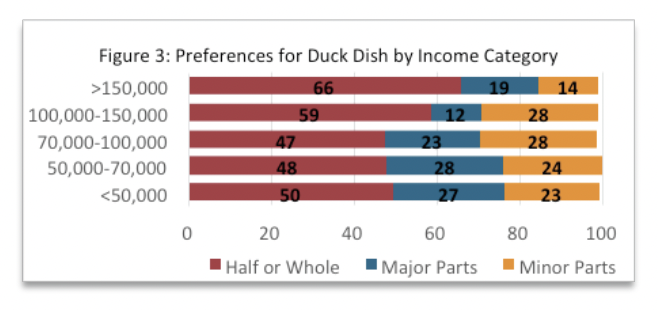

Based on consumer education, income, and behavior, three market segments emerge—two are traditional demand segments and there is one new demand segment. The traditional segments are mostly composed of low and middle-income consumers and still exhibit traditional preferences, while the new segment, composed of mostly high-income consumers, displays markedly more western preferences (Cui, 1999; Cui & Liu, 2000; Cui & Liu, 2001; Pan & Kinsey, 2002; Poon, 2006). The three consumer segments are detailed in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2. Duck Ordering by Frequency by Income Category

Figure 3. Preferences for Duck Dish by Income Category

Segment 1. The first segment is composed of consumers whose incomes have seriously fallen behind in the recent economic growth including those from economically depressed areas (such as Chengdu) or from less privileged backgrounds (such as migrants, or the less-educated). This segment is often labeled as the “Salary Class” and the “Working Poor.” Migrants probably make up a large portion of this segment because big economic gaps exist between large cities and rural areas in China. Under China’s residence control policies, residents in these four major cities who recently migrated from the small towns or rural areas often have disadvantaged status. Consumers in this segment have low incomes thus dine out less frequently and spend less when they do dine out. They also have a strong preference for local and traditional cuisine, which often contains strong-tasting, minor cuts and older ducks raised in Southern China. Despite these preferences, however, these consumers often order duck less frequently, but order major parts including breast and leg meat more often. This may be explained by the fact that traditional establishments often price duck at a premium price relative to other traditional meats such as pork, and the major parts are less tasty and less pricy on the same edible meat basis compared to whole or minor parts. So despite these consumers’ tastes, they are largely constrained by their low incomes to purchase more discounted entrees.

Segment 2. The second segment is composed of middle and rising-income consumers with some college education who have gained financially from the expanding economy, who often lived in cities with growing economies but retained strong national customs (such as Beijing), and may have been part of the newly affluent. This consumer segment is labeled as “White Collar” or “Emerging.” They often come from small households with only a few members, such as double career families, a few are migrants or families with one child. They often have less time to prepare food at home, and dine out more frequently than Segment 1. Although they also exhibit a strong preference for traditional or local cuisine, they have the income to dine out more frequently, they order duck more frequently, and they purchase whole duck entrees and minor cuts. They may have some form of college training and are from the middle income and purchase duck most frequently and order minor cuts and whole and half duck entrées more frequently than other segments.

Segment 3. The third segment is composed of highly-educated, high-income consumers, including those who have captured a share of the growing prosperity in globalized cities (such as Shanghai and Guangzhou). They have generally been exposed to western cuisine and culture. They are called the “Nouveau Riche”, “Emerged,” or “Affluent.” They come from mostly small, power-couple households or large (> 5) wealthy households, such as business executives and celebrities, who are likely to eat out frequently, but not necessarily with the entire family. They also pay considerably more when dining out and they have acquired modern tastes and have reduced desires for the traditional local tastes compared to the other two segments. Instead, they prefer other meats such as beef to duck, and when they do order duck, they prefer mostly major cuts and whole or half duck entrees. When they face falling incomes, they decrease the frequency with which they order duck and switch back to minor cuts which may be sold at a relative discount in globalized food establishments.

Other Factors. Age and gender are also related to consumer behavior and preferences. Older consumers order duck more frequently and prefer whole or half duck entrees, which likely reflects older consumers’ preference for traditional dishes, such as Peking Roast duck, over modern cuisine. Male consumers order duck dishes more frequently and prefer major cuts more than female consumers who prefer minor duck cuts. This is consistent with the tradition that Chinese females enjoy the taste of food more even at the cost of a lot more work at the table.

Restaurant Manager Affect Duck Preferences

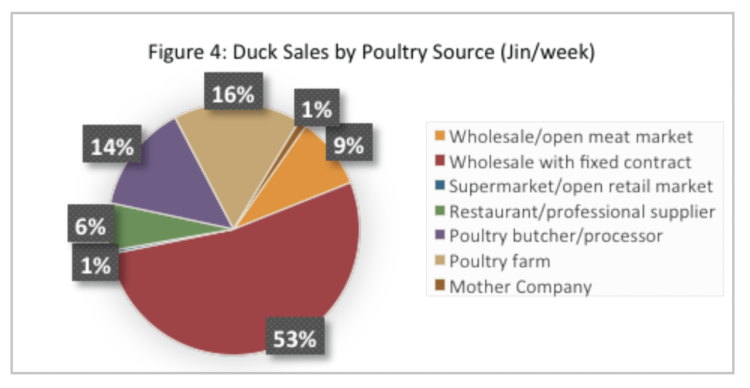

From the manager survey we found restaurants use seven sources for their ducks as shown in Figure 4. In descending order of use these are: contracted wholesalers, farms, butchers/processors, open wholesale markets, restaurant special suppliers, mother companies (for chained restaurants), and retailers.

Figure 4. Duck Sales by Poultry Source (Jin/week)

We also found there are four restaurant styles. The first category is composed of “mom and pop” style restaurants with low weekly sales volumes, low gross annual sales, and discounted prices. They mainly source poultry from a parent company or open wholesalers. The second category is composed of smaller, premium restaurants with low weekly sales volumes, low annual gross sales, but premium prices who mainly purchase from open retail/supermarkets, poultry farms, or poultry butchers/processors. The third category is composed of larger, premium restaurants with low weekly sales volumes, but high annual gross sales and high prices who mainly purchase from restaurant and professional suppliers. The final category is composed of large, inexpensive restaurants with large weekly sales volumes and high annual gross sales, but low prices. They mainly purchase from fixed-contract wholesalers. Categories two and three, with premium pricing, have stronger breed preferences evidenced by their higher use of EU/Cherry Valley or Chinese Natural breeds.

Market segmentation of restaurant managers who purchase duck can be compared on three dimensions: (1) Gender, (2) Age/experience, and (3) Education level.

Gender: There were more male managers than female managers and male managers typically had higher education levels. Restaurants with male managers sell higher volumes, achieve higher gross sales, use open wholesale or retail sources more often, have less breed preference, and often have a stronger preference for major cuts. Female managers more often use fixed-contract wholesalers or supply from a mother company, use Chinese Natural breeds, and prefer minor cuts.

We also found there are four restaurant styles. The first category is composed of “mom and pop” style restaurants with low weekly sales volumes, low gross annual sales, and discounted prices. They mainly source poultry from a parent company or open wholesalers. The second category is composed of smaller, premium restaurants with low weekly sales volumes, low annual gross sales, but premium prices who mainly purchase from open retail/supermarkets, poultry farms, or poultry butchers/processors. The third category is composed of larger, premium restaurants with low weekly sales volumes, but high annual gross sales and high prices who mainly purchase from restaurant and professional suppliers. The final category is composed of large, inexpensive restaurants with large weekly sales volumes and high annual gross sales, but low prices. They mainly purchase from fixed-contract wholesalers. Categories two and three, with premium pricing, have stronger breed preferences evidenced by their higher use of EU/Cherry Valley or Chinese Natural breeds.

Market segmentation of restaurant managers who purchase duck can be compared on three dimensions: (1) Gender, (2) Age/experience, and (3) Education level.

Gender: There were more male managers than female managers and male managers typically had higher education levels. Restaurants with male managers sell higher volumes, achieve higher gross sales, use open wholesale or retail sources more often, have less breed preference, and often have a stronger preference for major cuts. Female managers more often use fixed-contract wholesalers or supply from a mother company, use Chinese Natural breeds, and prefer minor cuts.

Age/Experience: Young, inexperienced managers more often use fixed-contract wholesale or get their duck supply from a mother company. They have less breed preference, and often order more already processed and cut duck parts in lieu of whole ducks. Older, more experienced managers often opt for open wholesale or retail, or farm supplied poultry, have some breed preference (mostly Chinese Natural breeds, followed by EU/Cherry Valley breeds), and buy whole ducks and then split them to obtain separate cuts.

Education Level: Less-educated managers sell more volume per week and have higher annual gross sales. They charge less per entrée, use fixed-contract wholesalers more often than poultry farms, butchers, and processors, and purchase EU/Cherry Valley breeds more often. Managers with higher education sell less but charge higher prices, use poultry farms, processors, and butchers more often than fixed contract wholesalers, and either use no particular breed or Chinese Natural breeds. Behavioral differences between the education levels of managers follow two common marketing strategies. Managers with less education buy a more generic wholesale bird and sell large quantities at discounted prices in a high volume-low margin strategy. Managers with more education tend to source selectively from farms, butchers, and processors, sell at high prices and use a lower volume-high margin strategy. One explanation for the divergence in breed preferences is than higher-education managers rely less on breed origin to determine quality whereas managers with less education perhaps rely more heavily on origin as an indication of quality (Bredahl, 2003; Knight et al., 2008).

Comparing Managers and Consumers

Although consumers and managers rank product attributes similarly, consumers rank product attributes more consistently than managers, and managers understand attribute meanings better than consumers.

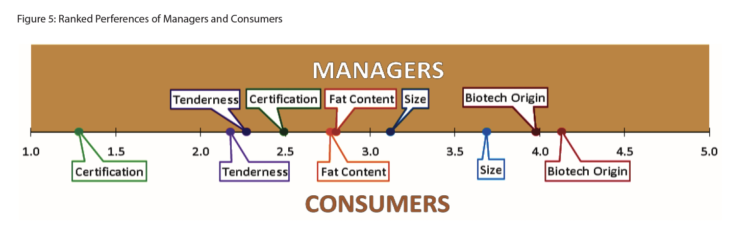

Consumers and managers were asked to rank five product attributes (1) safety certification, (2) bird size, (3) biotechnology country of origin, (4) tenderness, and (5) fat content. The rankings were from one to five with one being most preferred. Result for both managers (top) and consumers (bottom) are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Ranked Preferences of Managers and Consumers

These attributes represent different preferences managers and consumers may use when determining the value of each product and influence which product to purchase. Bird size can be determined prior to purchase, tenderness and fat content may be experienced after purchase and during consumption, and safety certification and biotech country of origin may or may not be linked with any post-consumption experiences.

Managers often disagree on the relative importance of each attribute making the average rankings converge toward the mean. Managers ranked tenderness as the most important attribute, followed by certification, fat content, size, and biotech country of origin. Consumers largely agreed on the relative importance of each attribute, thus the average rankings are more dispersed. Consumers ranked certification as the most important attribute, followed by tenderness, fat content, size, and biotech country of origin. Although consumers value safety certified products, it is uncommon to find certification labels for duck dishes, so they often rely on their eating experience based on tenderness, fat content, and size to determine restaurant quality and repeat patronage (Bredahl, 2003). As a result, managers often focus on improving the eating experience instead of using safety certification.

We asked consumers and managers about their understanding of the meaning of each attribute and found managers understand better than consumers. The highest percentage of consumers and managers understood tenderness, followed by size, and fat content. There was less understanding of certification, and biotech country of origin. Managers who understand the meaning of biotech country of origin is highest in Chengdu and Shanghai, which is probably a reflection of the entrance of foreign breeds in Shanghai and the strong preference for domestic breeds in Chengdu. Interestingly, nearly all managers in Beijing and Guangzhou understood safety certification, while only about