Converting Swine Grower-Finishing to All-In-All-Out: Will It Pay?

June 17, 1993

PAER-1993-9

Chris Hurt, Professor; George Patrick, Professor; and Chris Overend, Graduate Assistant

Converting Swine Grower-Finishing to All-In-All-Out: Will It Pay?

Chris Hurt, Professor; George Patrick, Professor; and Chris Overend, Graduate Assistant

All-In-All-Out (AIAO) management of swine grower finishing units is being considered by many producers. The mix of different ages and weights of pigs inherent in continuous flow management fosters disease trans-mission, which is reduced with AIAO. In AIAO management, pigs remain in the same group from birth to market. Facilities are thoroughly cleaned and disinfected between groups to achieve a high health status.

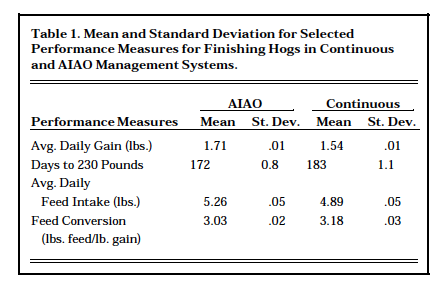

AIAO requires modifications to most existing buildings, as well as changes in management practices. The question for most producers considering AIAO is whether the shift will increase or decrease returns over time. A typical existing mid-western farrow-to-finish operation is used to examine the economics of conversion to AIAO in the grower-finishing unit of the facilities. Gains in production efficiencies for AIAO are based upon a Purdue study by Cline, et al.1 They found that AIAO grower-finishing hogs had higher daily gains, better feed conversion, and took fewer days to reach market weights (see Table 1). The differences were all statistically significant.

Capital costs for conversion and annual operating costs were estimated by the team of Purdue agricultural economists, agricultural engineers, animal scientists, and veterinarians who worked on the AIAO project^2 .

The existing facility in this case study was a 24-crate farrowing building with nursery and enclosed finishing. Farrowing was on a weekly plan with five sows farrowed each week for four weeks, and then four sows farrowed in the fifth week. An average of 38.5 pigs were weaned per week. Pigs remained in the nursery for five weeks, then were moved to a small pen in the finishing building. Pigs were later moved across the aisle, into a larger finishing pen, where they stayed until marketing. Total yearly production was 2,000 head of pigs weaned per year in the 120-sow operation.

How AIAO Affects Economics

The conversion from continuous to AIAO production not only involves changing from a weekly breeding and farrowing schedule to a group breeding and farrowing schedule, but many related factors that affect profitability. A list of the factors which should be considered before the shift to AIAO follows. The fac-tors are divided into those that increase costs and those that increase returns or reduce costs.

Table 1. Mean and Standard Deviations for Selected Performance Measures for Finishing Hogs in Continuous and AIAO Management Systems

Increased Costs

- Capital Costs

— Walls and pit dividers to

make finishing rooms

— Changes to the ventilation

of rooms

— Potential change in space

requirements

— Solid pen partitions in alley

ways to avoid nose-to-nose contact

— Lost profit opportunity in transition to a group system

- Variable Costs

— Cleaning detergents and

disinfectants

— More labor for cleaning

— More labor for the potential

of moving pigs more often— Added electricity and

repairs for cleaning

— Added maintenance to wall and pit dividers

Increased Returns Or Reduced Costs

- Less feed per pound of gain

- Fewer days to market, including:

— Reduced interest costs and

— The potential to produce more pounds of pork per year by utilizing the “saved days” in the grower-finishing unit

- Lower death loss

- Reduced medication costs

In addition, the conversion to AIAO may affect the farrowing, cleaning, and marketing schedules as well as other management practices of a producer.

How Buildings Should Be Modified

There are several ways to remodel finishing facilities for AIAO production. We elected to evaluate four alternatives. The objective of the first alternative was to minimize added capital, the objective of the second was to minimize added labor, and that of the third was a compromise of these two objectives. Finally, the fourth alternative examines returns if the full advantage of spreading fixed costs could be achieved. Although the farrowing and nursery phases were also con-verted to AIAO in all cases, this analysis considered only the grower-finishing phases of production.

The first alternative minimizes the capital investment required by using the existing space to its maximum. To do this, the first 32 feet of the finishing unit are modified to be a grower unit. The remaining portion of the building is modified to be three finishing rooms. The first finishing room has 10 pens where small pigs were allocated about 6 square feet each. Each pig has 7.5 square feet of space in the second room and about 9 square feet in the third finishing room. Pigs are moved a total of five times. This includes from farrowing to the nursery and then to the grower. After leaving the grower, the pigs are in each of the finishing rooms for five weeks. Some pigs are placed in pens with unfamiliar pigs at each move.

This strategy minimizes the amount of capital investment by maximizing the use of existing space, but it requires large amounts of additional labor. Each time a room is emptied, it is cleaned and sanitized. The grower unit and each of the three finishing rooms need to be cleaned 10.5 times per year. Total yearly production is 2,000 pigs weaned. Depreciable capital costs are $13,092 and include insulation for the new grower room, replacement feeders in the grower, heaters in the grower, and the added walls to form the three finishing rooms. Variable costs for items such as detergents, electricity, added labor, and pit curtains are $5,687 per year.

The second alternative minimizes the amount of additional labor needed by minimizing the number of times the pigs are moved and thus the number of times rooms are cleaned. The finishing building is remodeled into 4 grower-finisher rooms. Because 40 pound pigs are given the amount of space that would be required at market weight, there is a need to extend the finishing facility an additional 32 feet. Furthermore, because there is no separate grower unit, all of the finishing facilities require insulation, heaters, some added ventilation equipment, as well as room and pit dividers.

A total of 192 pigs are weaned every 5 weeks and moved into the nursery for a 4 week stay. Then they are moved to a finishing pen where they stay until marketed at 28 weeks of age. No additional moves are required once the pigs are moved to finishing at about 40 pounds. Pigs need to be moved only twice. Total production is 2,000 head weaned per year, the same as in the continuous system. Capital costs are$62,140 and the variable costs are

$3,149 per year.

The third alternative, the com-promise alternative involves converting the first four pens on each side of the alley in the finishing room to a grower unit. The pigs stay in this grower unit for five weeks and move into finishing rooms at about 80 pounds. Pigs are moved out of the grower unit into one of three finishing rooms. The finishing rooms are modified by building walls to separate rooms and dropping a pit curtain. Insulation, heat, and mechanical ventilation are added in the grower unit only.

There is a need to build an additional 8 feet onto the finishing unit. Pigs are moved three times in this system: once out of farrowing, the second time out of the nursery, and the third time out of the grower. The pigs are placed into pens with unfamiliar pigs twice, once out of farrowing and once out of the nursery. Total production is 2,000 pigs weaned per year. Capital costs for this alternative are $18,804, and annualized variable costs are $3,471 per year.

For the first three alternatives it was assumed that the producer can-not gain the full advantage of the 6.6 percent fewer days to market. To gain the full advantage of conversion to AIAO, they would have to produce 6.6 percent more pounds of pork in a year with the same facilities. This may be difficult. Although the AIAO pigs get to market sooner, the producer cannot simply buy feeder pigs to use the “saved space.” Few producers can produce 6.6 percent more pigs with the same farrowing and nursery facilities. The easiest way to achieve this additional output might be to increase market weights of hogs by 6.6 percent. However, heavier weight market hogs might be subject to price discounts.

In the evaluation of the fourth alternative, we assumed the farm is able to fully utilize the 6.6 percent fewer days by increasing yearly out-put by a similar amount. In this final alternative, the economics include two additional impacts. The first is the cost-lowering impact of spreading the fixed costs over a larger output. The second is increased returns from the larger scale of operation, if production is profitable.

Economics Depend on How You Remodel

A farrow-to-finish budget was used to determine the costs and returns for each remodeling alternative. The year 1991 was used as the base year, with $2.28 per bushel for corn and$310 per ton for 40 percent hog supplement. A long-term average price of $48 per hundredweight for market hogs was assumed. Costs of production were based upon the average cost data for farms on the 1991 Iowa State University Hog Records. Labor and fringes were charged at $8 per hour and depreciation was seven years for equipment and 10 years for buildings. Interest rates were set at 9 percent on fixed capital and 8 per-cent on operating capital.

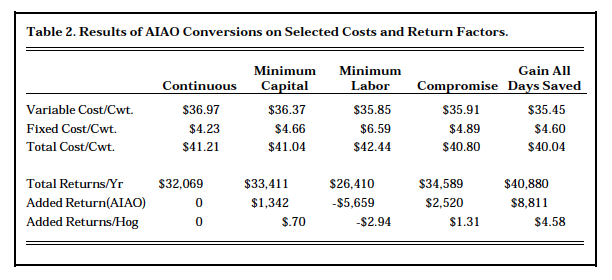

Results of the economic analysis are shown in Table 2. The five columns represent the continuous system and the four remodeling alternatives in the conversion to AIAO. The results show that an objective of minimizing either the use of labor or capital may be unwise. The minimum capital remodeling alternative did lower total costs modestly from $41.21 to $41.04 per hundredweight and increased the returns above all costs per hog marketed by $.70. How-ever, the minimum labor alternative was not profitable and reduced the returns per hog marketed by $2.94. The compromise, which did not attempt to minimize the use of labor or capital, was the most profitable conversion alternative. Returns above all costs increased by $1.31 per hog marketed.

The importance of finding some way to utilize the extra finishing capacity created by fewer days to market can be seen in the last column. If an operation could increase output to use fully the days saved, costs were lowered by $1.17 per hundredweight, and the returns were increased $4.58 per hog marketed relative to the continuous system.

Conclusions

We believe this study demonstrates that many hog producers may gain from conversion to AIAO in grower-finishing. It was our intention to budget conservatively, so actual returns are likely to be greater than those shown here.

A number of factors are critical in the decision of converting to AIAO in grower-finishing. First, results depend on how remodeling is done. This is clearly demonstrated by the differences among the four remodeling alternatives considered.

Second, it is clear from this study that the ability to utilize effectively the saved days due to fewer days to market is critical to gaining the full advantage of AIAO in grower-finishing. These advantages can be gained more easily in building a new set of buildings where the farrowing house can be sized with the fewer days to market in mind. The $4 to $5 per head range may be a reasonable estimate for the advantage of AIAO in a new set of buildings.

Third, it must be recognized that AIAO is a different hog production system. It is dependent upon scheduled movement and cleanings. If the skills to manage a tight production schedule and the time to stay with the schedule are not available, conversion to AIAO in grower-finishing should not be considered. AIAO increases the use of two important resources on the farm-capital and labor, and much of the increased labor is for the less-than-glamorous function of washing rooms. In the compromise system, the labor requirement increased about 0.1 hours per hog marketed, and the added investment in the first year was about $10 per hog. Using these as rough guidelines, a farm marketing 3,000 head might expect to increase labor requirements about 300 hours per year and invest $30,000 to make the modifications.

Finally, it is important to note that each hog farm has a unique set of buildings. Conversion to AIAO in grower-finishing will be much easier for some than for others. We have demonstrated that conversion to AIAO in finishing can increase income on a typical midwestern farm. However, the question of whether AIAO in grower-finishing will pay on an individual farm will depend on the unique characteristics and costs of inputs for that farm.

References

- Cline, T.; V. Mayrose; A. Scheidt; M. Diekman; K. Clark; C. Hurt; and W. Singleton. “Effect of All-In/All-Out Management on the Performance and Health of Growing-Finishing Swine.” Purdue Swine Day Report 1992, pp. 9-12.

- Hurt, C.; G. Patrick; D. Jones; T. Cline; V. Mayrose; M. Diekman; L. Clark; and A. Scheidt. “Economics of All-In/All-Out Management for Growing-Finishing Hogs.” Available from the authors.

Table 2. Results of AIAO Conversions on Selected Costs and Returns Factors