Cost Structure and Control: The Dominant Issues in Farm Management

March 17, 1993

PAER-1993-1

Michael Boehlje, Professor

Many farmers and analysts have spent considerable time, money, and energy on policy concerns and marketing strategies for farmers, and time spent on these areas can be financially rewarding. But the importance of cost and cost structure on bottom line performance should be the manager’s primary concern. This discussion will emphasize the importance of a fundamental and essential understanding of how costs affect profitability and detail the management strategies to enhance profitability.

Agriculture is essentially a commodity business where product differentiation is not impossible, and difficult. Porter’s discussion of competitive strategy indicates that there are three fundamental approaches to acquiring a sustainable competitive advantage: a cost leadership approach, a product differentiation approach, and a focus or specialization approach (Porter). Because of the commodity nature of agriculture, the differentiation strategy is difficult to implement. Consequently, most farms must develop a competitive advantage through cost leadership or focused specialization; even specialization will not be an effective long-term strategy if costs are not competitive. It may not be too strong a statement to conclude that, because agriculture is a commodity business, the low-cost producer will be the survivor.

Although such a conclusion may be accurate and useful, it does not go far enough in assessing how costs and cost structure affect management strategies. In contrast to many manufacturing and nonfarm businesses, the cost structure in production agriculture is characterized by a relatively large proportion of total costs that are fixed and a low proportion that are variable. Fixed costs do not vary with output and are commonly defined to include depreciation, interest, insurance, and taxes. These costs are incurred whether or not a crop is planted (the costs are sunk) whereas variable costs will increase or decrease as a function of output. Land rent may present a special case; with cash rentals the rent payment is obligated for the season and payable irrespective of output, so it is a fixed cost. With share rentals, the rental payment does adjust with the amount of output produced, so it is a variable cost. The length of lease may also affect its fixity, although the rental market is sufficiently thin that it is difficult for a producer to be “in and out” of that market, so many leases are in reality long-term in nature and the lease payments are a fixed cost.

The cost structure has significant and powerful implications for management decisions in production agriculture.

- The first implication of the high-fixed-cost structure of production agriculture is that plant “shut-down” decisions are much less responsive to price decreases than in most industries. For example, in the auto-mobile manufacturing business, where a large proportion of the total cost of production is variable, modest declines in automobile prices will result in shut-down of the factory because prices won’t cover variable costs. Recall that in the short-run, the plant shut-down decision occurs when prices or revenues do not cover variable costs; fixed costs and total costs are irrelevant in the plant shut-down decision. In contrast, with a much smaller proportion of total cost being variable, as is the case in production agriculture, prices and revenues will decline substantially more before plant shut-down occurs. Consequently, farmers are more inclined to produce themselves into a surplus situation than are their counterparts in the manufacturing sector.

- A second implication is that traditional “cost control” strategies are less effective in a high-fixed-cost industry. If a large proportion of the costs are fixed, traditional strategies that by their very nature focus on variable costs have less potential impact because variable costs are a lower proportion of the total cost. Cost control in production agriculture should focus on fixed costs not only because they are a larger pro-portion of the total, but also because there is typically substantial variation in fixed costs between high- and low-profit farms, and thus significant opportunity to affect profitability.

- In a high-fixed-cost industry, fixed asset utilization is critical, because fixed assets are the basic source of fixed costs. This is particularly the case for producers under financial stress. For most producers in financial trouble, the problem is excessive fixed costs rather than variable costs such as seed, fertilizer, chemicals, or feed. And excessive fixed costs are reduced in only two ways, either 1) selling or disposing of the fixed assets that are resulting in the fixed costs, or 2) increasing through-put (increased volume with the same asset base) to spread the fixed costs over more out-put. Though-put can be increased by tighter scheduling of building use using flow scheduling techniques, operating machinery and equipment more hours per day or days per year, by custom operations, or renting land, etc. Traditional cost containment strategies are generally ineffective for many firms under financial stress because the cause of that stress is excessive fixed costs, not excessive variable costs.

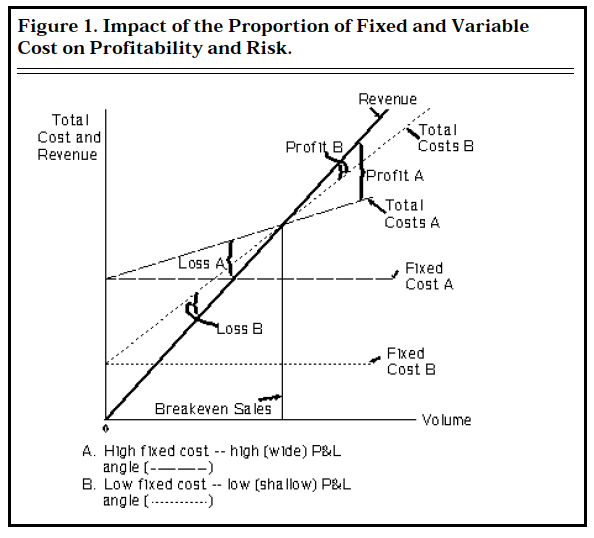

- Cost structure also affects the sensitivity or responsiveness of profitability to sales volume and level. Figure 1 illustrates the implications of different cost structures for a business venture. To make the analysis easier to understand, it is assumed that total costs for Firm A and Firm B are both equal to total revenue at the same break-even level of sales. Note the significantly greater change in profit and loss angle as one deviates from the point of break-even sales volume when fixed costs comprise a higher proportion of total costs (Firm A), compared to the nar-row profit and loss angle when vari-able costs dominate the cost structure (Firm B). Sales volume above the break-even level has a much larger impact on profits for the high-fixed-cost firm (Firm A), com-pared to the low-fixed-cost firm (Firm B), and likewise volume below break-even results in a larger loss. Consequently, maintaining volume above break-even has a much higher payoff for the high-fixed-cost firm, and volume below break-even results in more risk of loss. In essence, the low-fixed-cost firm is not hurt as much by volume declines, nor does it benefit as much from volume increases — there is a higher payoff for a firm like this to emphasize cost control rather than volume to increase profits. For the high-fixed-cost firm, volume is paramount.

- A high-fixed-cost firm is less flexible — less adaptable. It is more difficult for such a firm to respond to changing economic conditions, adjust to new market realities, or adopt new technologies and ways of doing business. With the rapid change occurring in production agriculture, a firm that has more capacity to respond to that change, to adapt, and to be flexible has a higher chance of surviving. The challenge becomes flexibility at what cost? If flexibility results in inefficiency and high costs — it may not be worth the “price” that is being paid.

High-fixed-costs result in high risk (particularly if those fixed costs are also cash costs) and reduced flexibility, so one strategy that should be considered to reduce risk for firms with high-fixed-costs is to convert fixed costs into variable costs. Such conversion is difficult in production agriculture, but not impossible. Most of the fixed costs in agriculture are a result of strategies to obtain the use of fixed assets such as machinery, equipment, real estate, and facilities through ownership. Obtaining the use of these same resources through such arrangements as leasing, rental, custom farming, etc., or other contract-for-services strategies (i.e., custom feeding in a commercial feed-lot) will convert fixed costs to variable costs. Clearly, this conversion should not be done without evaluating the implications for quality and availability of the service and the comparative cost of obtaining the ser-vice/resource with various strategies.

Figure 1. Impact of the Proportion of Fixed and Variable Cost on Profitability

- A high-fixed-cost industry is also an industry with a high “entry fee.” This means it is more difficult for new entrants to acquire the resources and financial backing to enter the industry, which is certainly the case in agriculture. In a market with few producers who are producing differentiated products, a high “entry fee” would also provide some protection from competitors who are less likely to enter and take market share. Thus, there is generally less competition and lower risk of losing market position, power, or share if the “entry fee” is high because of the dominance of fixed cost. But in agriculture, which is a commodity business (i.e., little product differentiation) with a number of producers worldwide, this argument doesn’t apply.

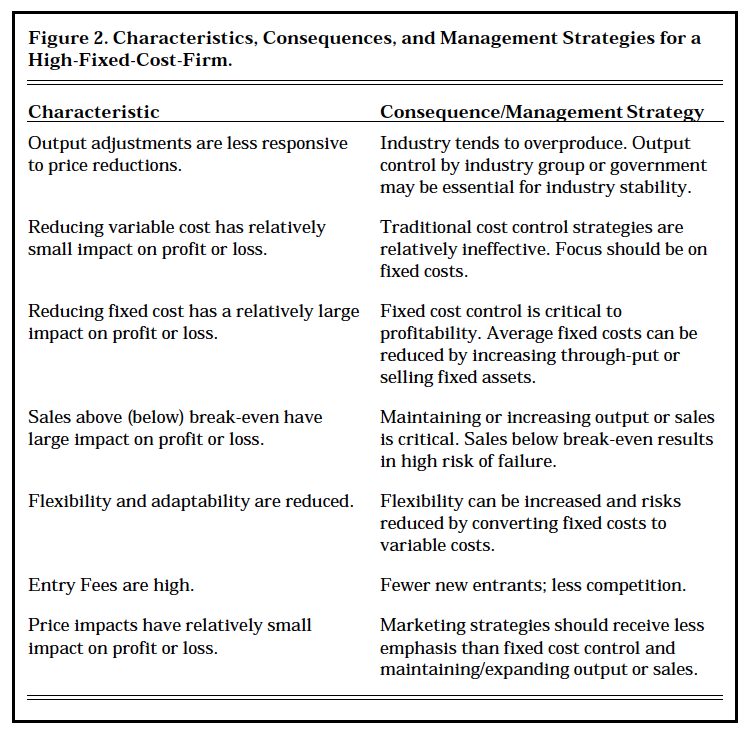

Table 2. Characteristics, Consequences, and Management Strategies for a High-Fixed-Cost-Firm

- Finally, as reflected in Figure 1, in a high-fixed-cost industry with a high profit and loss angle, increasing revenues by increasing product price has an identical absolute but smaller relative or percentage impact on profitability for a given level of sales. Similarly, a decline in product price because of a less effective marketing strategy and/or price discounts results in the same absolute but smaller relative decline in profitability for a high-fixed-cost industry. Consequently, relative to other means of enhancing profit margins such as increasing efficiency or reducing costs, price enhancement is less critical for the high-fixed-cost firm and more critical for the low-fixed-cost firm. In fact, for a low-fixed-cost firm, a significant decline in prices or price discounting to maintain market share can quickly result in losses and financial failure. Price declines or discounts are relatively less painful for a high-fixed-cost firm.

- In summary, the cost structure in agriculture has significant and powerful implications for management decisions. As indicated in Figure 2, the high-fixed-cost structure of the industry affects cost control strategies, pricing decisions, and risks, and reinforces the critical nature of maintaining through-put. The cost structure also has policy implications — a high-fixed-cost industry will tend to overproduce and frequently will need some form of output control by an industry group or the government to maintain industry stability.