Critical Questions About the Farm Crisis: Causes and Remedies

March 13, 1999

PAER-1999-05

Otto Doering, Professor and Phil Paarlberg, Associate Professor

Just over a year ago every-thing seemed settled. The new Freedom to Farm legislation (the FAIR Act) ended farm programs as we knew them, eliminating acreage restriction on crops that could be planted, eliminating supply control with land set asides. Now we have “transition” payments to farmers that are fixed amounts in contrast to the counter cyclical target payments that increased when prices were low. Freedom to Farm passed because prices were high, exports were supposed to increase over the next decades, and agribusiness consultants claimed that increased land in production (no set-asides and a smaller CRP) would not reduce prices, just create more jobs. Times were good. For 1996 wheat land owners and producers got almost $2 billion in payments under Freedom to Farm, compared to less than 40 million they would have received under the old program. Corn land owners and producers received a little over $5 billion in payments in 1996 and 1997, instead of just a little over $1 billion under the old program.

What a change today. The Asian financial crisis, declining exports, big crops in the bins, and a good ’98 harvest have lowered prices. Gloom replaces optimism. Exports of agricultural products by the United States for fiscal 1998/99 are forecast at 52 billion dollars, 4 billion dollars lower than in 1997/98. Freedom to Farm payments looked good with high prices, but with low prices producers feel the decline in government support under the new program.

Did Asia Do It?

Many believe the economic problems in Asia caused most of our commodity price problem. During the 1990s, Asia emerged as a major market for U.S. agricultural products. However, many of the factors causing the cur-rent financial crisis, like overextended credit, had initially boosted economic growth and fueled agricultural imports. In the summer of 1997 this house of cards collapsed.

While serious for most U.S. export commodities, the price impacts to this point have not been as large as the media portrays. The Asian problems have not been the major cause of the decline in U.S. agricultural prices. Using the elasticities the Eco-nomic Research Service used to analyze effects of the Uruguay Round trade agreement, the devaluations and falling aggregate demand in Asia resulted in a short-run 4.1 percent drop in the wheat price, a 3.7 percent drop in the coarse grains price, and a 10.2 percent fall in the soybean price. We estimate that the devaluations and falling national income reduced the price of beef 1.5 percent, pork by 9 percent, and poultry by 5 percent. Rice, in contrast, shows a much larger price effect, falling 29.9 percent. Except for rice, these Asia-specific impacts are much smaller than the overall price declines observed, and rice has other mitigating factors that have reduced even its large overall price decline. A recent analysis using a global macro-economic model with an agricultural sector supports these small price impacts.

Why might price declines be smaller than expected? First, the Asian countries most severely affected were neither major agricultural importers nor exporters. Of the Asian Tigers (Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Hong Kong, and Taiwan) only Korea was a large importer of U.S. agricultural products, with a market share of 5 percent, and Korea received over 1 billion dollars in General Sales Man-ager (GSM) credit guarantees. The remaining six nations combined accounted for 13 percent of U.S. agricultural exports. Of these, the most severely affected, Indonesia, Thai-land, and Malaysia, buy only small amounts of agricultural goods. Rice is again a different story, with Indonesia and Thailand being important importers or exporters. Data for Japan and China through May 1998 do not show a large fall in trade. Japan shows a small, but persistent, drop in purchases from the United States during the past two years. Except for December 1997 and May 1998, Chinese purchases are at or above year earlier levels. The data for the Asian Tigers show that monthly purchases of U.S. agricultural commodities fell sharply starting in the fall of 1997, but because they are small customers, the impact is modest.

Adverse impacts of the Asian Crisis may worsen. For the 1998/99 year, the problems experienced by the Asian Tigers could spread. Japan alone accounts for roughly 18 per-cent of U.S. agricultural exports —our largest single export market. Japan’s current recession follows years of low growth. Nearly half of its exports go to the weakened markets in Asia. The Japanese banking system holds extensive bad debts, and past attempts to stimulate domestic demand failed. In China, which accounts for 3 percent of U.S. agricultural exports, slowed eco-nomic growth and unmet reforms may force a currency devaluation to boost exports. Competitive devaluations by other Asian nations may follow. Latin America and Brazil in particular, which are large buyers of U.S. agricultural goods and a rival exporters of some, are experiencing currency and financial problems related to the Asian Crisis.

If the Asian problems have not been the major cause, how do we account for the sharp fall in commodity prices? Weather and the production response to the high prices of 1996 both weigh in. Despite the strong El Niño in 1997/98, expectations of short global food supplies failed to materialize. Production of all grains worldwide rose from 1,872 million tons in 1996/97 to 1,889 million tons in 1997/98. With excellent crops in South America and the United States, world oilseed production rose from 261 million tons in 1996/97 to 287 million tons in 1997/98. Production forecasts for 1998/99 continue to be positive. Current forecasts for the United States show record or near record production. USDA projects world grain production to fall only slightly in 1998/99 to 1879 million tons and estimates world oilseed pro-duction to remain at a high level as the U.S. soybean crop offsets a return to normal crops in South America.

It is the combination of these negative forces that has so sharply reduced agricultural prices and called into question the decision to adopt the Freedom to Farm legislation. Since the middle 1990s the world has added around 150 million tons to the average level of annual world grain output. The concern now is that the economic problems in Asia will spread to other major markets for U.S. agricultural goods—in Japan and in Latin America—while global food supplies remain at record levels. If this happens, recovery will be a three-to-five-year process.

Is such an outcome likely? There is little to support the idea that recovery in Asian economies will boost demand before early in the next century (only a year or two away). What about adjusting output? Arguments for and against a quick supply response can be mustered. Even the authors disagree.

Paarlberg sees a drop in global sup-ply occurring within the next few years. With Freedom to Farm, U.S. farmers will react to market signals and will abandon marginal lands.

The European Union has the ability and will use set-asides to cut area. Other exporters, like Argentina and Australia, are more open to world prices than in the 1980s and will adjust. Also weather can play a role. Already Russia appears to have a crop disaster, and the United States is extending concessional sales to that nation. We could move substantial food aid to the former Soviet Union this winter (but Congress appears unwilling). Looking at our past experience, La Niña could cut U.S. crop yields by 10 percent or more. A 10-per-cent decrease in U.S. coarse grains yields translates into an output loss of around 25 million tons, well above the 10 million tons of coarse grains exports some have estimated lost due to the economic problems in Asia.

Doering has a different view. He argues that farmers have few alter-natives and so production is very price inelastic.

It will take several years of low prices to cut production. Actual policy reforms resulting from the Uruguay Round were limited, and most countries continue to protect farmers while severing the link between domestic prices and world prices. Those nations will not adjust production. In nations where reforms did occur, governments will intervene to support farm prices or farm incomes. Relying on weather to cut output is a risky strategy given the recent experience with El Niño which was also supposed to tighten world food supplies. At least one La Niña event was associated with a 20-percent yield increase in the United States!

Is Freedom to Farm a Failure?

Freedom to Farm has done what it was supposed to do, and it has done it very well. It removed planting and acre-age restrictions, gave farmers production signals from commodity markets rather than from price supports, and stabilized government program expenditures at fixed amounts that can be counted on for budgetary purposes. The problem is that the 1996 optimism about demand for commodities has not panned out, prices have gone down, and with, low prices, Freedom to Farm does not pump as much extra cash to landowners and producers as the old programs would have.

What are the Issues and Alternatives Now?

On September 2nd, Senator Tom Harkin, in the political rhetoric of an outspoken critic of the FAIR Act, said, “There are two things we can do to save the ‘96 Farm Bill.” He wanted to uncap loan rates and “for this year only” institute a farmer-held reserve. Farmers had freedom to farm, according to Harkin, but they needed “freedom to market,” —in this context a farmer-held reserve to hold grain off the market until prices are higher. He concluded that “we are facing a farm crisis in America unlike anything we have seen in a long time.”

Congress was already laying out alternatives to deal with the farm financial problem when Harkin spoke. With the October 1998 omni-bus spending bill, Congress made available large disaster payments ($2.58 billion) to producers who suffered extreme weather and other crop and livestock losses. In addition, Congress made Fair Act payments that would normally be made in 1999 available to farmers in 1998. This belies the claim of keeping expenditures predictable. Will Congress let landowners and producers go through 1999 without additional payments? Not likely.

Under FAIR, the Loan Deficiency Payment (LDP) still does provide a safety net under prices. If markets fall below a very low fixed loan rate, the government will pay the farmer the difference between the loan rate and the market price. Unlike under the old program, the government does not take title to grain and accumulate stocks. The FAIR Act sets the loan very low to prevent outlays except in extremely low price situations like we had late this summer. However, it does provide a low level of counter cyclical support and can trigger substantial government payments.

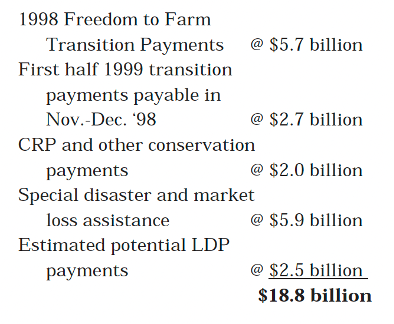

In the pre-election budget compromise, Congress also voted an additional “one time” payment to FAIR program farmers (about half of the 1998 transition payments) of over $3 billion. If farmers took just the first half of their 1999 transition payments at the end of 1998 and locked in LDP payments at the early fall commodity prices, the federal commodity and conservation expenditures might look like this:

Figure 1. Federal commodity and conservation expenditure

This is a big increase over the $5.7 billion FAIR Act transition payments and the $2.0 billion conservation payments that would have been paid in a normal year. The political issue is that many want even more government payments in low price years—the extreme example being the $26 billion expenditure in 1986 during the farm financial crisis.

The Issues Joined

The cusp of the debate that resulted in the Clinton veto of the Ag. Appropriations bill on October 7th, 1998 revolved around:

- The distribution as well as the amount of the payments

- The extent to which agricultural programs return to being counter cyclical entitlements subject to large outlays during bad times.

Clinton, with Daschle looking over his shoulder, vetoed the Ag. Appropriations bill, H.R. 4101,

“because it fails to address adequately the crisis now gripping our Nation’s farm community.” The message also stressed the inadequate “safety net” of Freedom to Farm and supported Daschle and Harkin’s proposal to lift the cap on the marketing loan. Clinton said, “I firmly believe and have stated often that the federal government must play an important role in strengthening the farm safety net.”

The Daschle and Harkin debate also questioned the beneficiaries of the transition payment. Freedom to Farm puts the landowner in the best position to capture the transition payments and capitalize them into the value of the land. The equity concern, while it has been raised, will not likely be addressed directly. Congress has been unwilling to have agricultural programs means tested like other income transfer programs, or to really tackle the large farm versus small farm issue. Congress’s traditional solution pumps some money to most parties and very liberal amounts to a few.

Lifting the cap on the marketing loan is exactly what the Republican leadership (especially Dick Armey, who dislikes farm programs more than almost anything else) wanted to avoid at all costs. That is one reason the GOP leadership rushed to move the 1999 Freedom to Farm payments ahead to 1998 and approved the disaster and market loss assistance payment to farmers—to keep the structure of Freedom to Farm. Lifting the cap would destroy the discipline of fixed payments and take us back to the countercyclical payments of old without supply control.

The Decision for Now—Does It Settle the Issues?

In the pre-election rush, Congress has spoken. The market-based char-acter of the Fair Act itself has been preserved, but Congress has gone beyond the program and increased income transfers to agriculture. Congress also proved again it is unable to enforce discipline on crop insurance, allowing those who did not take the required crop insurance under Freedom to Farm to receive the disaster payments if they promise to take subsidized crop insurance for the coming two years. Where does this leave us?

- The income transfers beyond the Freedom to Farm program will dampen the market-based supply response that might otherwise have occurred in the United States (proving Doering right for the wrong reasons).

- However, Freedom to Farm payments and added government transfers fall below the payments that probably would have been made under the old program.

- Congress demonstrated again that it can hardly resist sending aid to disasters—making subsidized crop insurance that much more difficult to sell.

- This year proves that the FAIR Act will be challenged when prices are low, and foretells of a real debate in 2002 when FAIR expires—unless, of course, prices are very high in 2001 and 2002. If it so chooses, the Commission on 21st Century Production Agriculture may have an opportunity to suggest another course. Income insurance, anyone?