Crop Machinery Benchmarks

June 13, 2014

PAER-2014-5

Michael Langemeier, Professor and Assistant Director of the Center for Commercial Agriculture

The continued increase in size of tractors, combines, and other machinery has enabled farms to operate more acres and reduce labor use per acre. However, this increase in machinery size also makes it increasingly important to monitor machinery investment and cost per acre. This article discusses and illustrates crop machinery investment and cost using a case farm. The first section of the article illustrates the estimation of machinery costs for a tractor. The second section illustrates the estimation of machinery investment and cost for a case farm. The third section discusses factors impacting machinery investment and cost.

Estimating Crop Machinery Costs

Machinery costs can be divided into two primary categories: ownership costs and operating costs. Ownership costs are often referred to as overhead, indirect, or fixed costs. These costs do not vary with machine use intensity during the year. Operating costs are often referred to as variable or direct costs because they vary with machine use during the year.

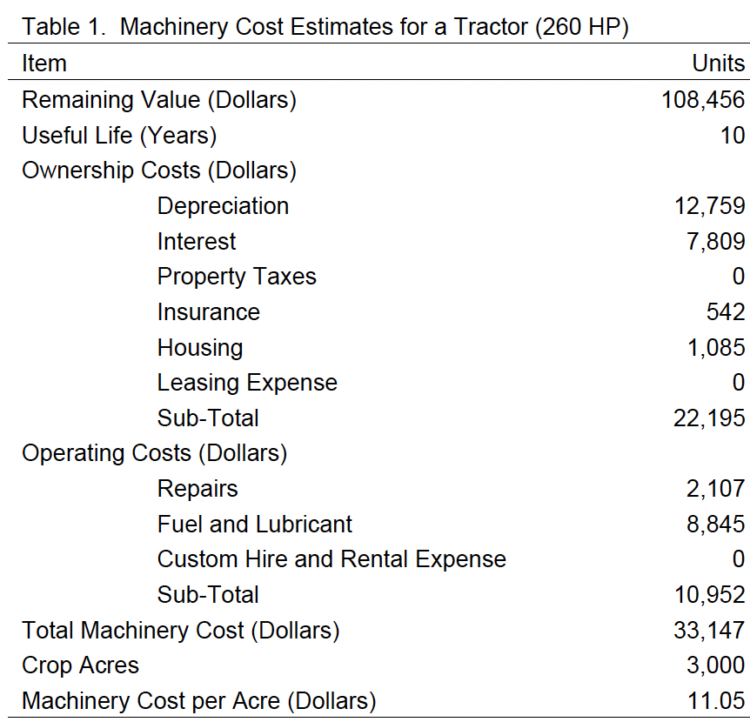

Table 1 illustrates ownership and operating costs for a tractor owned by a case farm. This farm does not have livestock so all of the relevant costs can be assigned to the crop enterprise. If a farm has livestock production, individual machinery costs need to be allocated between the crop and livestock enterprises.

Table 1. Machinery Cost Estimates for a Tractor (260 HP)

Ownership costs include depreciation, interest, property taxes, insurance, housing, and leasing cost. Depreciation is a non-cash expense that represents the reduction in asset value resulting from age, wear, and obsolescence. There are several methods that can be used to compute depreciation. Two common methods are the straight-line and declining balance methods. The idea is to mimic the actual decline in the machinery value over time. If the straight-line method is used, depreciation is computed by subtracting salvage value from original cost and dividing the result by the asset’s useful life. Intensity of asset use and obsolescence should be taken into account when defining the useful life of an asset. IRS regulations compute depreciation and define the asset’s life for tax purposes. Tax depreciation is typically higher in the early years of the asset’s life and smaller in the later years of the asset’s life. For benchmarking purposes, it is preferable to use a depreciation method and useful life other than those used for tax depreciation.

Depreciation is computed in Table 1 using the list price, salvage value (20 percent of original cost), and useful life of one of the tractors used by the case farm discussed below. Annual depreciation for the tractor is $12,759.

Interest is included as an ownership cost to reflect the fact that the money used for machinery investment has alternative uses. In other words, capital used for machinery investment has an opportunity cost. Interest is included as a cost regardless of whether the asset is purchased with debt, equity capital, or a combination of both. Interest cost can be computed by multiplying the remaining value of an asset by a long-term interest rate. Alternatively, interest cost can be computed by adding salvage value to original cost and dividing the result by two, and then multiplying by a long-term interest rate. This method uses the average value or the mid-life value in the computation.

In Table 1, interest cost is computed by multiplying the remaining value of a tractor that is four years old by a long-term interest rate (7.2 percent). Annual interest cost for the tractor represented in Table 1 is $7,809.

Other ownership costs include property taxes, insurance, housing, and leasing. Property taxes apply only to taxes related to machinery, which are common in some states. Leasing cost represents any annual lease payments for machinery. Other annual ownership costs for the tractor represented in Table 1 are $1,627.

Operating costs include repairs, fuel and lubrication, and custom hire or rental expense. Some estimates of operating costs also include labor. Annual repair costs vary with age, intensity of use, and machine type. It is particularly important to note that repair cost increases over time or as the asset ages. This fact often leads to a tradeoff between higher ownership costs and lower repairs in the early life of the asset and lower ownership cost and higher repair costs later in the asset’s life. Annual repair costs for the tractor represented in Table 1 are $2,107.

Fuel and lubrication includes gasoline, diesel, oil, and other lubricants. Using a diesel price of $3.60, annual fuel and lubricant costs for the tractor represented in Table 1 are $8,845.

As noted above, labor costs are sometimes included in machinery cost estimates. These costs would include field time as well as time spent fueling and lubricating, repairing, and transporting machinery.

Custom hire and rental expense should be included as a machinery operating cost. If a farmer receives custom hire income and the amount received is relatively small, this income can be subtracted from other machinery costs to arrive at total machinery costs. The subtraction reflects the fact that the costs associated with custom hire income would not have been incurred if the farm had not performed the custom operations. If custom hire income is relatively large, the farm should seriously consider analyzing the custom farm enterprise or activity as a profit center.

Summing the ownership and operating costs for the tractor represented in Table 1 yields an annual cost of $33,147. This farm has 3,000 acres of crops. Dividing the number of crop acres by the ownership and operating costs gives us a machinery cost per acre for the tractor of $11.05.

Machinery Investment and Cost per Acre

Two commonly used benchmarks to evaluate the efficient use of machinery are machinery investment per acre and machinery cost per acre. Machinery investment per acre is computed by dividing total machinery investment (i.e., investment in tractors, combines, and other machinery) by crop acres or harvested acres. In regions where double-cropping is prevalent, using harvested acres gives a more accurate depiction of machinery investment.

Machinery investment per acre typically declines with farm size. It is important for farms to compare machinery investment per acre with similarly sized farms and to examine the trend in this benchmark to evaluate machinery use efficiency. A farm with a relatively high machinery investment per acre needs to determine whether this high value is a problem. If the farm faces serious labor or timeliness constraints, this benchmark may be relatively high. However, if this benchmark is high due to the purchase of assets used to reduce income taxes, the manager needs to think about whether this is a profitable long-term strategy (i.e., is the farm going to have high costs per acre due to this strategy)?

Machinery cost per acre is computed by summing depreciation, interest, property taxes, insurance, housing, leasing, repairs, fuel and lubricants, and custom hire and rental expense, and dividing the resulting figure by crop acres or harvested acres. Again, in regions where double-cropping predominates, using harvested acres is preferable.

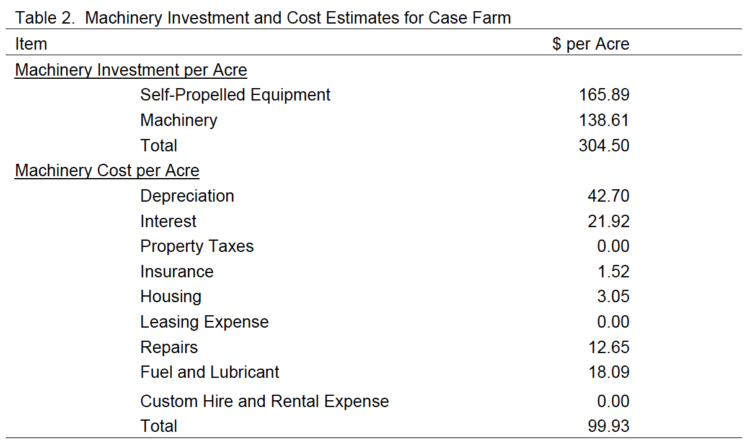

Crop machinery investment and cost for a case farm located in White County Indiana is presented in Table 2. This case farm has 1500 acres of corn and 1500 acres of soybeans. Machinery investment per acre is $304.50 for the case farm. This case farm does not custom hire any of the tillage operations. Machinery costs include depreciation, interest, insurance, housing, repairs, and fuel and lubricant. Machinery cost per acre for this case farm is $99.93. The three largest costs were depreciation ($42.70 per acre), interest ($21.92 per acre), and fuel and lubricant ($18.09 per acre).

Table 2. Machinery Investment and Cost Estimates for Case Farm

Unfortunately, crop machinery benchmarks are not common, but some information is available from Kansas and Illinois. Crop machinery investment per harvested acre was $259 and cost per harvested acre was $88 for non-irrigated crop farms participating in the Kansas Farm Management Association program in 2013 (www.agmanager.info/kfma). The amounts for the case farm discussed above are certainly above these figures. However, Brad Zwilling, Jim Locher, and Dwight Raab in a June 22, 2012 farmdoc daily article illustrate machinery value per acre for farms with 250 to 5000 acres. A farm with 1500 acres would have a machinery investment per acre of approximately $425 per acre while a farm with 3000 acres would have a machinery investment per acre of approximately $375 per acre. The crop machinery investment per acre for the case farm is below these amounts.

A recent study by Langemeier and Ibendahl (2014), indicated that farms with above average crop machinery investment and cost per acre had average values of $429 and $124, respectively. The values for the case farm are below these values.

The discussion above focused on machinery benchmark comparisons among farms. It is just as important to track the trend in the machinery benchmarks over time on the same farm. Increases in machinery investment and cost are often related to decreases in financial efficiency such as lower asset turnover ratios and higher depreciation expense ratios.

Factors Impacting Machinery Investment and Cost

There are several factors that impact machinery investment and cost per acre. One of these factors is machinery selection. Field capacity, availability of labor, tillage practices, crop mix, and timeliness constraints are all important considerations when selecting machinery. Purchasing larger machinery ensures that operations will get done in a more timely manner, but also can lead to higher machinery investment and cost per acre unless the farm expands by renting or buying additional land.

A second factor impacting machinery investment and cost relates to the alternatives available for acquiring machinery. Alternatives include ownership, rental, leasing, and custom hire. To increase control over use and timeliness of machine use, most farm managers prefer to own machinery. If ownership is the preferred option, a farm needs to carefully monitor machinery investment and cost. Factors that can lead to reductions in investment and cost include the following: using smaller machinery, increasing annual machine use, holding onto machinery longer before trading, purchasing used machinery, using alternatives to ownership such as custom hire, and farming more intensely (e.g., utilizing double-cropping). Of course, many of these factors may decrease timeliness, which could be particularly detrimental during planning and harvesting seasons. Thus, as with most machinery issues a balance between controlling machinery investment and cost, and timeliness needs to be reached.

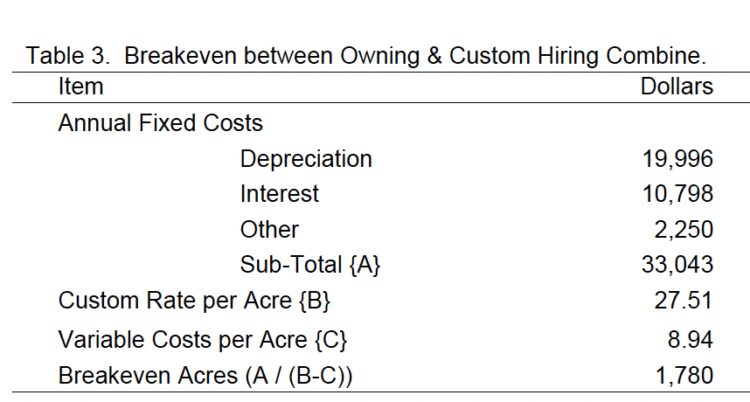

For machines that are used infrequently, it is important to compare ownership costs to custom hire charges. Of course, availability and timeliness concerns are pertinent to the choice between these two options. As indicated above, machinery ownership costs typically decline as acres and production increases. Custom hire rates, on the other hand, typically exhibit a fixed rate per acre. When data is available, a breakeven point where the decision switches between custom hiring an operation and owning a machine can be derived. Table 3 contains the relevant data for the case farm. The breakeven acres for this farm are 1780. If this farm had less than 1780 acres, it would be less costly to custom hire the harvesting operations on this farm. Since this farm has 3000 acres, it makes sense for the farm to own a combine.

Table 3. Breakeven between Owning & Custom Hiring Combine.

A third factor that impacts machinery investment and cost involves replacement decisions. Many farms follow one or a mixture of the following strategies: keep and repair, trade often, trade when income is high, or invest each year. The “keep and repair” strategy is often used by farms that have one or more individuals that are mechanically inclined. The “trade often” strategy is often used by farms with severe timeliness constraints. For example, if a large farm produces primarily corn, most of their crop needs to be planted and harvested in a narrow window. This farm may thus choose to trade often so that machines are not down during the critical periods. Many farms trade when income is high. When income is high, the farm has the cash flow to purchase machinery and also reduces income taxes. Finally, some farms invest in machinery in most years. This strategy spreads out the cash flow requirements as well as the loan payments.

Concluding Comments

As farms continue to adopt technology that is labor saving but capital intensive, it becomes increasingly important to evaluate machinery efficiency. Two machinery management benchmarks to do this are machinery investment per acre and cost per acre. Farm managers should calculate these benchmarks each year and then monitor them over time. Understanding your machinery economics has great value in potentially lowering costs, increasing output and throughput, and in making decisions such as whether to own, lease, or custom hire machinery.

For additional information on machinery benchmarks see:

Edwards, W.M. “Estimating Machinery Costs.” Ag Decision Maker. PM-710, Iowa State University, November 2009.

Farm Financial Standards Council. Financial Guidelines for Agricultural Producers, 2008.

Kay, R.D., W.M. Edwards, and P.A. Duffy. Farm Management, Sixth Edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

Langemeier, M. and G. Ibendahl. “Crop Machinery Benchmarks.” Journal of the American Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers. 77(2014).

Lazarus, W.F. “Machinery Cost Estimates.” University of Minnesota, May 2012.