Deciding to Switch to Narrow-Row Corn

June 12, 1999

PAER-1999-10

Alan Hallman, Graduate Assistant and J. Lowenberg-DeBoer, Professor

Deciding to switch to narrow-row spacing in corn is not just about increasing yield. It is about balancing costs and benefits of switching to narrow-rows. Whether switching increases profits depends on location, current agronomic practices for both corn and soybeans, changes needed to harvest narrow-row corn, the resale value of narrow-row equipment, and other factors. The purpose of this study was to estimate the potential profitability of switching to either 20-inch or 15-inch row corn. This article focuses on expected profits from narrow-row corn, but it is important to note that narrow-row corn may increase technology risk.

Many factors influence the profitability of narrow-row corn. Yield response to narrow-row spacings varies regionally. Most studies show a greater yield response in the northern Corn Belt. Root worm in first year corn is a growing problem in parts of the eastern Corn Belt. The cost of corn root worm insecticide per acre increases sharply with narrow-rows, doubling as rows go from 30-inch to 15-inch row width. Some farmers now have separate planters for corn and soybeans. Costs can be reduced if both corn and soybeans can be planted with the same planter. This can have implications for the time of planting and the number of acres farmed.

If a narrow-row combine breaks down, it may be difficult to find a neighbor or custom operator to complete the harvest, and if narrow-row corn is not widely adopted, the narrow-row corn head may not have much resale value. (Lowenberg-DeBoer and Hallman (1998) provide fuller discussion of risks related to narrow-row corn).

Yield Data

The study used partial budgets to estimate the expected annual profits from switching to narrow-row corn. The focus is on long-term costs and benefits. The short-term transition costs of making the change are not included. A complete summary of the data and methods is available in Lowenberg-DeBoer and Hallman (1998).

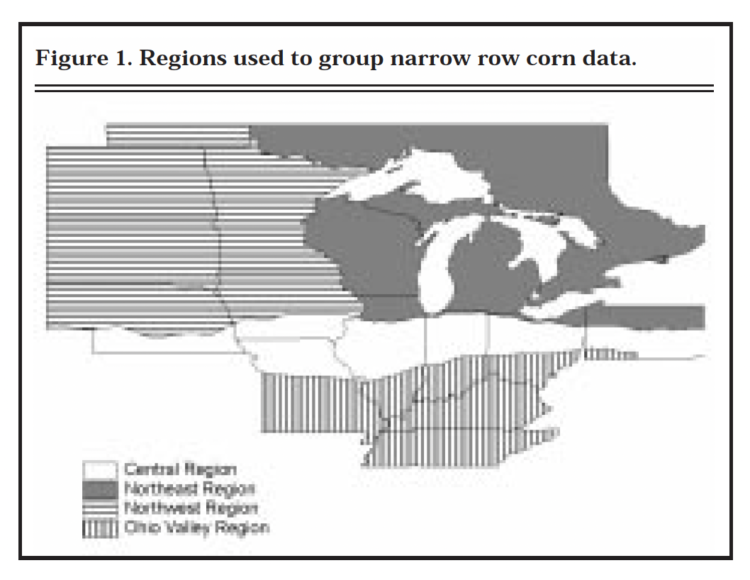

A key question is corn response to narrower rows. Much data is available from university and industry studies. In an effort to summarize this data, publicly available data was pooled from across North America. This data came from scientific publications and the INTERNET. The data was grouped into the regions illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Regions used to group narrow row corn data

Studies tested a wide variety of row spacings, and it was not clear that small changes in row spacing (e.g., 22 to 20 inch or 20 to 15 inch) had much impact, so data was grouped into 30-inch and narrow-row categories. The 30-inch category includes row widths from 29.9 to

31.5 inches. The narrow-row category includes row widths from 25.6 to 10 inches, with an average of 18.1 inches. There are 140 data points, each with a 30-inch and narrow-row component. Similar results to those using the public data set were obtained by using a data set from Pioneer Hybrid, containing 1322 data points, but a smaller geographical reach.

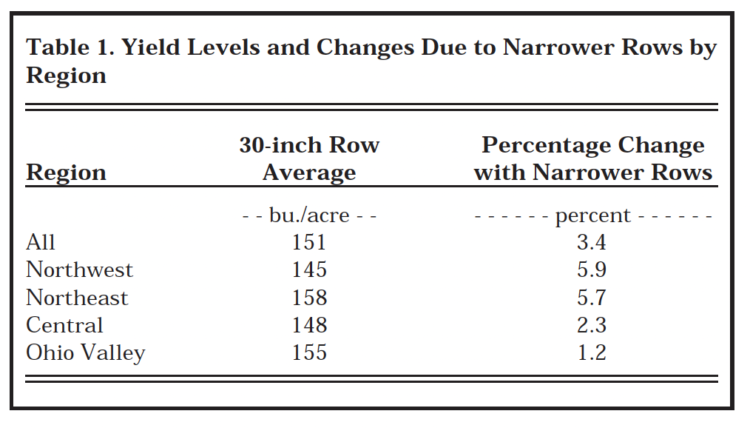

The average percentage change in yield when going to narrower rows is around 6% in the northern Corn Belt, but only 1% to 2% in the Central or Ohio Valley Regions (Table 1). This is consistent with average yield differences identified by other researchers. It should be noted that the publicly available data may overestimate the yield response to narrow-rows because of reporting bias. The scientific review process tends to encourage the reporting of trials with significant (i.e., larger) differences and discourage reports in which no significant differences were found.

Machinery Costs

Equipment costs vary by size of equipment and acreage covered. To make the analysis concrete, the focus was on the type of equipment used on larger commercial farms, moving from 16 30-inch rows to 24 20-inch rows or 32 15-inch rows for planting 900 acres of corn. Machinery costs would probably be somewhat higher for smaller equipment on smaller farms. The 20-inch row comparisons assume that the producer has a planter used only for corn. Average price of new equipment from three major manufacturers was used to estimate 20-inch and 30-inch row costs.

* This method estimates the annual payment that would be needed to exactly pay for the equipment assuming compound interest. The annual payment estimate combines depreciation and opportunity cost of capital.

The 15-inch row comparisons assume the farmer currently plants corn in 30-inch rows and soybeans in 15-inch rows with the same planter equipped with “row splitters.” When planting corn in 30-inch rows, only every second planter unit is used. For 15-inch row corn the producer simply uses all the planter units for corn, just as is done for soybeans. The equipment required in this case is a 15-inch row cornhead, narrow tires and frame extensions for the combine. The cost of a 16-row 15-inch cornhead was obtained from Clark Machine, Howard, South Dakota.

Table 1. Yield Levels and Changes Due to Narrower Rows by Region

A sinking fund* approach was used to annualize equipment costs. Original cost was estimated at 85% of manufactures’ list price. A 10% interest rate was used. The planter and corn head were given a useful life of 10 years, and narrow tires and frame extension five years. Esti.mated resale value and repair costs were based on the number of years and hours of use. Insurance and taxes were also included. It was assumed that the current combine could support a somewhat heavier narrow-row corn head.

For the case of the corn only planter used on 900 acres, the switch from 30-inch row to 20-inch row requires an investment of about $25,000. Annual equipment costs increase about $6.54/a if the cornhead can be sold at the end of 10 years.

For the-15 inch row case, no additional planter investment is required, but the cornhead costs about $17,000 more than a 30-inch head of the same width. The additional investment required is about $20,000, and annual equipment costs increase about $5.97/a. The increase in corn head and planter costs for the 20-inch case is greater than the increase in the costs of the corn head in the 15-inch case.

Resale value of the cornhead has only a small impact on annualized costs. If the narrow-row corn head is used 10 years and junked instead of being sold or traded in for the average resale value, the costs of switch.ing to narrower rows increases by only $0.85/a.

Other Costs

Corn root worm insecticide is applied per linear foot of row. As row width narrows the number of feet of row per acre increases. Following insecticide label rates, the analysis assumed that insecticide use increases in proportion to the increase in row length per acre. For example, for 20-inch rows, the row length and insecticide increase by 50%. Insecticide label rates sometimes include a per acre limit on the amount of insecticide to apply. It may be necessary to change insecticides because for some products the amount required in narrow-rows exceeds per acre limits. At average 1998 prices, the increased insecticide cost would be $7.97/a for 20-inch rows and $15.94/a for 15-inch rows.

Corn and soybean prices were USDA 1988-1996 averages for a state in each region. Fertilizer costs for increased yield was charged at crop removal rates. Additional dry.ing and hauling were included. Plant population and seed costs were assumed to be the same for both 30-inch and narrower rows.

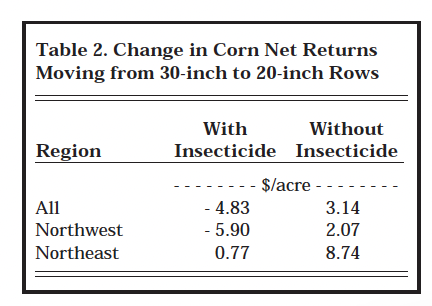

Table 2. Change in Corn Net Returns Moving from 30-inch to 20-inch Rows

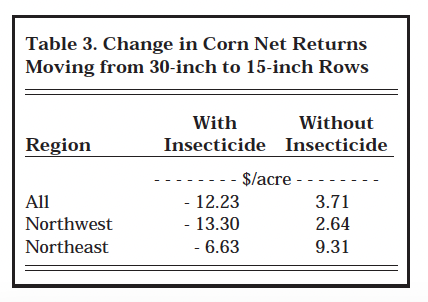

Table 3. Change in Corn Net Returns Moving from 30-inch to 15-inch Rows

Results for 20-inch Rows

For farmers that have a corn only planter and do not need insecticide on first-year corn, the switch to narrow-row is modestly profitable in the Northeastern and Northwestern regions (Table 2). In other areas the yield increase is not enough to pay for the added equipment costs.

When insecticide is required on first-year corn, narrow-row corn has only a slight positive return in the Northeastern region, probably not enough to compensate for the costs of making the transition and the added risk. Most of Indiana is in the Central and Ohio Valley regions where average yield benefits are not enough to make 20-inch row corn profitable.

Results with 15-inch rows

For farmers who already have a corn and soybean planter and do not need insecticide on first-year corn, the switch to narrow-row is profitable in the Northeastern and Northwestern regions (Table 3). It is about breakeven in the Central and Ohio Valley regions, which includes most of Indiana. Because of the doubling of insecticide cost in 15 inch rows, narrow-row corn is unprofitable for continuous corn or when root worm problems occur in first-year corn.

Conclusions

This study indicates that for farmers in the northern Corn Belt who do not need insecticide on first-year corn, narrower rows are a potentially profitable technology. Because of the increased insecticide cost with narrower rows, the technology is not currently profitable for those who use insecticide on first-year corn or grow continuous corn. Given publicly available data on yield, narrow-row corn does not appear to be profitable in the central and southern Corn Belt, including most of Indiana.

This analysis looked at costs for large-scale corn growers currently using 16 row 30-inch equipment. Narrow-row costs for smaller equipment would be slightly higher. Benefits to narrow-row corn for smaller operations are expected to be slightly less than those estimated, but the general conclusions would be the same.

The equipment scenarios used for this study focus on those which change only corn production practices, either by changing row width on a corn only planter or by using an existing soybean planter for corn. There are cases in which soybean row width might be affected by the planter choice. For example, a producer might decide to switch from a 30-inch row corn only planter and a 7.5-inch row soybean drill to a single 15-inch row planter for both crops. When soybean row width is widened, the potential reduction in soybean yield must be factored into the profit estimate.

One potentially important limitation of this study is that it did not include the possibility that more rapid canopy closure in narrow-rows would improve weed control and lower herbicide costs. This aspect may be particularly important with the new herbicide tolerant corn hybrids.

Growers who do not decide to move to narrow-rows now should regularly revisit that decision. Technological change may quickly alter the economics. For example, a genetically modified root worm resistant corn could eliminate the need for insecticide and make narrow-row corn profitable in northern Corn Belt areas with root worm problems in first-year corn.

References

“Cost, Average Returns and Riskiness of

Switching to Narrow row Corn,” Symposium on Exploring New Crop Management

Systems, American Society of Agronomy

Annual Meeting, Baltimore, October, 1998.