Deer and Elk Farming in Indiana: Economic Opportunity for Rural Communities

June 23, 2012

PAER-2012-06

Alicia English, Ph.D. Candidate; John Lee, Professor

Small-scale agricultural enterprises can have important economic impacts for families in rural communities. Indiana has been among the fastest growing states in the number of deer and elk farms. These farms are producing deer and elk mostly for hunting preserves, but also live animals for breeding stock, hides, semen, antlers, velvet, and processed meat products. This article provides estimates of the dollar and employment impacts from Indiana deer and elk farming and hunting preserve operations.

Indiana and National Farms

There are deer and elk farms in a number of Indiana locations, but the top 10 counties for deer and elk farming, ranked by the number of BOAH permits (Indiana Board of Animal Health) in 2011, were LaGrange, Marshall, Allen, Elkhart, Kosciusko, Miami, Noble, DeKalb, Adams, and Whitley counties. These counties are located in the North Central and Northeast portions of the state and tend to be rural, with the exceptions of Allen (Ft Wayne) and Elkhart counties. LaGrange County had 60 permitted farms.

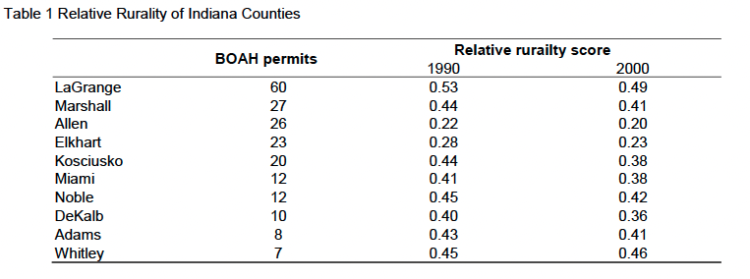

Using estimates from Waldorf (2007), the top 10 BOAH permit counties are given a relative rurality score that is shown in Table 1. The maximum rurality score on this scale in Indiana is 0.57. The top 10 counties by number of BOAH permits in 2011 have rurality indexes ranging from 0.20 to 0.49 for 2000. Thus, the majority of deer and elk farms are located in rural counties.

Table 1. Relative Rurality of Indiana Counties

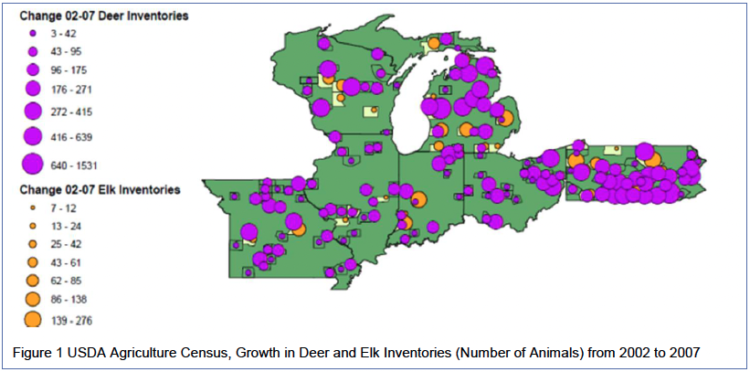

According to USDA Agricultural Census data, the states with the largest increases in cervid (deer and elk family) operations were Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Ohio. Lancaster, Pennsylvania had the largest gains, with a 1,531 deer inventory increase from a population of 491 in 2002 (USDA NASS 2011). Elk inventories in contrast had smaller inventory increases. States with the largest increases were Pennsylvania, Michigan and Indiana. In Indiana, opportunities for deer and elk farming and hunting operations have increased the number of licensed breeders by 19% since 2006, with a majority of the distribution in the northeastern counties of the state (Indiana State Government 2011).

What about the entire country? A 2007 cervid study conducted by Texas A&M University estimated there were 7,828 cervid operations nationally. This estimate included approximately 1,600 Amish operations that consider deer and elk breeding an opportunity to diversify and generate income on relatively small acreage (Anderson, Frosh and Outlaw, 2007).

What Is the Market?

Growth in neighboring states represents a potential opportunity and some challenges for Indiana deer and elk farmers. Their market relates to the selling of deer and elk products and breeding stock. This includes live animal for breeding and hunting, hides, semen, antlers, velvet, and processed meat products. Hunting preserves typically serve as the primary end market for many of these animals, especially those that are high valued trophy bucks.

A number of the hunting preserves Indiana farms sell to are in other states. For example, Pennsylvania has approximately 1000 deer and elk breeding farms and over 47 cervid hunting preserves. Indiana, in contrast, has 388 farms and only four hunting preserves. Indiana regulations will phase out these four gradually, and no new Indiana entrants are currently to be allowed. The deer and elk farm to preserve ratio is 21:1 in Pennsylvania, while the same ratio is 97:1 in Indiana.

Figure 1. USDA Agriculture Census, Growth in Deer and Elk Inventories (Number of Animals) from 2002 to 2007

Additional problems can arise when Hoosier breeders try to rely on out-of-state markets. Other states may choose to regulate imports of live animals, semen and other cervid products. A review of different state rules and regulations regarding the cervid farming industry reveals a wide variation in policies. Some states have banned the importation of live animals from other states in an attempt to support their own breeding industries. Still others have restricted importation based on possible health risks due to the fear of diseases spreading to their own herds. In addition, deer and elk breeding operations are always at risk for disease outbreaks from wild herds. Indiana DNR and BOAH, as an example, are monitoring wild Indiana deer herds for the spread of bovine tuberculosis from herds in Michigan and Minnesota.

Economic Impacts

The total economic impact of the deer and elk farming industry in Indiana is the sum of the direct, indirect, and induced effects. The direct effects are those related to the economic activity and employment in raising the animals. The indirect effects relate to the purchases of goods and services made by the deer and elk farms in the local economy. Examples include the purchases of equipment, feed, fencing, veterinary services, transportation, utilities, and insurance. These purchases result in the economic impact multiplying through the other sectors of the rural economy.

The induced effects result from the spending by other businesses and people in the state that support the deer and elk farming and hunting preserves. For example, catered meals to hunting lodges involves local businesses that start with the caterer purchasing food, hiring staff, and buying equipment and vehicles from other local businesses. Through these activities, economic activity is spread throughout the local and state economy.

In order to estimate the economic impact of the cervid industry in Indiana, two surveys were conducted by the Indiana Deer and Elk Farming Association in 2011. These asked members to provide estimates of the values of animal sales and purchases; herd inventory, operations and facilities costs; equipment and veterinary and feeding expenses; and hunter- and hunting-specific operational expenses. These values were used with the IMPLAN (Impact Analysis for Planning) model developed by the USDA Forest Service. The multiplier coefficients for Indiana came from The Economic Impact of the Indiana Livestock Industries (Mayen and McNamara, 2007).

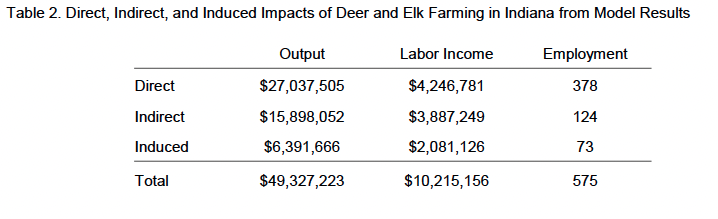

The total economic impact of deer and elk farming in Indiana is estimated to be $49.3 million in 2010. This includes the value of sales at $27.0 million (Table 2). The industry generates over $22.3 million in indirect and induced effects for the economy of Indiana. Total labor income resulting from deer and elk farming exceeds $10 million dollars annually.

Table 2. Direct, Indirect, and Induced Impacts of Deer and Elk Farming in Indiana from Model Results

Total employment from Indiana’s deer and elk farming is estimated at 575 people. It should be noted that this input/output model result may understate the real employment impact for Hoosiers. This is because many deer and elk farmers rely on part-time hourly employees or on family members to provide labor. In fact, survey results for the state’s industry revealed 497 full time employees and over 2,600 part time hourly workers statewide. Survey results suggest labor income exceeds $16.2 million dollars annually. In addition, total wages paid by hunting preserve operations for cooks, guides, and labor results in approximately an additional $200,000 in seasonal income.

Summary

Indiana is among the fastest growing states in deer and elk farming operations. These enterprises are predominately owned and operated by small acreage rural land owners. Many of these deer and elk farmers engage in this activity as a means to improve household income and employment in economically limited rural areas.

This study estimated the Indiana industry to have an economic impact of $49 million in 2010, and survey results indicate a labor income of over $16 million to families involved in the industry. While the total dollar impact is small compared with the traditional agricultural sectors of the state economy, the economic footprint of deer and elk farming can be important to individual families in rural Indiana counties.

Future growth in this industry is expected to be driven in large part by the market for deer and elk by hunting preserves. Currently more than 90% of Indiana animals purchased go to hunting preserves. There are headwinds for the industry, however, because the state of Indiana is phasing out in-state preserves, and shipments from Indiana to other states may be limited by those states due to restrictions regarding the transportation and health risks of out-of-state animals. This means that Indiana producers will need to build strong relationships with out-of-state preserve managers and strive to meet all regulatory rules of those states.

The complete report is available at: http://www.indianadeer.net/IDEFA_EconomicImpactAnalysis_final.PDF

For more information about this interesting industry, visit the Indiana Deer and Elk Farmers’ Association at http://www.indianadeer.net/ .

References

Anderson, D., B. Frosh, and J. Outlaw. 2007. Economic Impact of the United States Cervid Farming Industry. Texas A&M, College Station.

Census Bureau. 2011. State and County Quick Facts http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/18/18183. (November 1, 2011).

Indiana State Government. 2011. BOAH Premise IDs. http://www.in.gov/boah/2328.htm (October 31, 2011).

Users Guide to IMPLAN MIG, Inc. 2011 Version 3.0 Software. http://implan.com/V4/index.php?option=com_multicategories&view=categories&cid=222:referencemanualusersguidetoimplanversion30software&Itemid=10 (October 31, 2011).

Mayen, C. and K. McNamara. 2007. The Economic Impact of the Indiana Livestock Industries. Purdue Extension ID-354.

Census of Agriculture. USDA- NASS. 2011. 2002 and 2007. http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/ (November 1, 2011).

Waldorf, B. 2007. What Is Rural and What Is Urban in Indiana? Purdue Center for Regional development. PRCD-R-4.