Environmental Awareness and Attitudes: Large-Scale Farmers and the General Public*

July 13, 2000

PAER-2000-11

George F. Patrick, Professor

Do farmers and the general public have the same knowledge and views on environmental issues? This article compares a national survey of the general public with a group of

large-scale farmers from the eastern Cornbelt. There are substantial differences between producers and the general public in environmental knowledge and views on environ-mental issues. The large-scale farmers were much more knowledgeable about the environment than the general public. However, while farmers feel environmental policy has “gone too far,” the general public feels pol-icy has “not gone far enough.” These results suggest that agriculture will continue to face formidable challenges in the environmental policy area.

In 1997, the National Environ-mental Education and Training Foundation (NEETF), together with Roper Starch Worldwide, conducted a national telephone survey of 1501 randomly selected individuals 18 years of age or older. A number of questions were asked about attitudes toward environmental rules and regulations, compensation for loss of value from land use restrictions, and views of the environmental future. A 12-item multiple-choice test of environmental knowledge was also given. A subset of the same questions was given in a written questionnaire to participants in the 1997 Top Farmer Crop Workshop (TFCW) held at Purdue University (Appendix A). Although the TFCW participants are not a representative sample of all farmers, they have characteristics of the farmers who produce the bulk of the nation’s food and fiber. The 41 male respondents are large-scale farmers, growing nearly 1950 acres of crops in 1997 (primarily corn and soybeans) on owned, cash- rented, share-leased and custom-farmed land. All had gross farm incomes of more than $100,000. These producers averaged 40.6 years of age and had completed more than 3 years of education beyond high school. Less than 10 percent of respondents received more than 25 percent of their gross income from livestock.

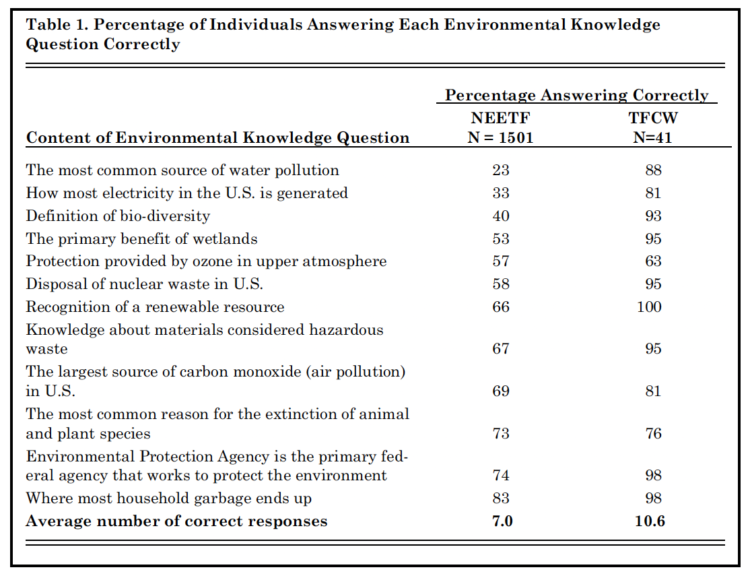

The TFCW participants correctly answered an average of 10.6 questions on the 12-item test of environ-mental knowledge, with over 56 percent responding correctly to 11 or more of the questions. In contrast, only 11 percent of the NEETF sample responded correctly to 11 or more questions. The general public aver-aged 7.0 correct responses, and the average increases to 7.8 if only men are considered. If only college graduates and those with post graduate education are considered, respondents with educational levels similar to those of the TFCW participants, the number of correct responses increased to 7.9 and 9.1, respectively. Although the TFCW participants demonstrated a much higher level of environmental knowledge, less than 5 percent thought that they knew a lot about environmental issues and problems, as compared to 16 percent of the men in the NEETF study.

Table 1 compares the percentage of the NEETF sample and the TFCW participants who answered each of the 12 environmental knowledge questions correctly. TFCW participants had much higher percentages of correct responses on questions related to sources of water pollution, how electricity is generated, the definition of bio-diversity, and primary benefits of wetlands. The percentages of correct responses for the two groups were similar for the protection offered by ozone in the upper atmosphere and the primary reason for the extinction of animal and plant species.

Table 1. Percentage of Individuals Answering Each Environmental Knowledge Question Correctly

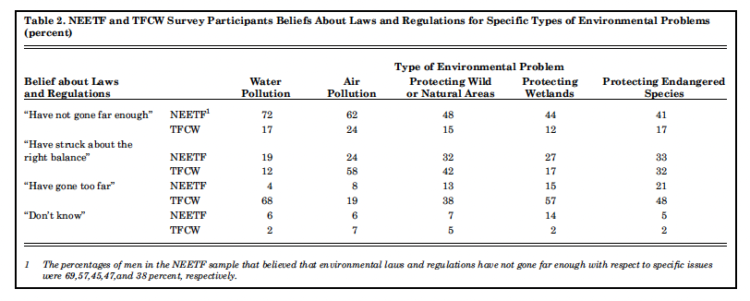

Table 2. NEETF and TFCW Survey Participants Beliefs About Laws and Regulations for Specific Types of Environmental Problems (percent)

Appendix A: Environmental Knowledge Quiz

When attitudinal responses about environmental beliefs are compared, there are also differences. About 47 percent of the NEETF respondents believed that environmental laws and regulations in general had not gone far enough, while 16 percent believed they had gone too far, and 26 percent believed that about the right balance had been struck. For the TFCW participants, less than 5 percent believed environmental laws and regulations had not gone far enough, 46 percent believed they have gone too far, and 39 percent believed it was about the right balance. Some 10 percent of each group “did not know.”

Table 2 compares the beliefs of the two groups with respect to laws and regulations in five specific environmental problem areas. There are very sharp contrasts in the beliefs of the groups. For example, 72 percent of the NEETF respondents believed that laws and regulations had not gone far enough in the water pollution area, while 68 percent of the TFCW participants believed that these laws and regulations had gone too far. About 57 percent of the TFCW participants believed that laws and regulations had gone too far in protecting wetlands, and 48 percent had similar beliefs with respect to endangered species. More than 40 percent of the NEETF respondents believed that laws and regulations had not gone far enough in any of the five environmental problem areas. Beliefs of the two groups were the closest on air pollution.

On the issue of whether compensation should be paid for the lost value of land because of use restrictions related to protecting endangered species or wetlands, less than 5 percent of the TFCW participants as compared with 30 percent of the NEETF study participants thought that compensation should not be required. Some 61 percent of the NEETF participants thought compensation should be paid. Almost 71 percent of the TFCW participants thought compensation should be paid, and nearly a quarter thought it should depend on how much value was lost due to restrictions. With a choice between environmental protection and economic development, some 74 percent of the college graduates in the NEETF study felt that environmental protection and eco-nomic development “could go hand in hand,” while 26 percent felt “a choice must be made.” Only 8 percent of the TFCW participants felt “a choice must be made.” Although 60 percent of the TFCW participants felt environmental protection and economic development “could go hand in hand,” nearly 30 percent selected the response that the choice “would depend.” In the NEETF study, the “would depend” response was not included, and only 4 percent of all respondents volunteered it.

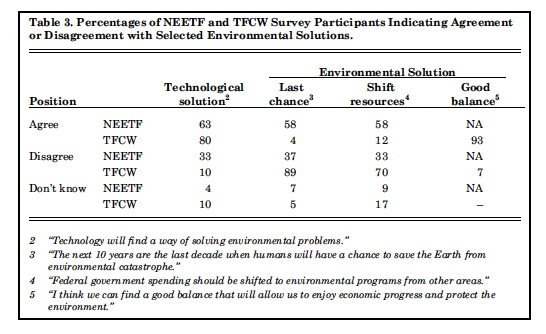

Table 3. Percentage of NEETF and TFCW Survey Participants Indicating Agreement or Disagreement with Selected Environmental Soultions

Differences of opinion between the NEETF and TFCW samples with respect to future solutions of environmental problems were less pronounced. As indicated in Table 3, 63 percent of the NEETF sample and 80 percent of the TFCW sample agreed or strongly agree with the belief that “technology will find a way of solving environmental problems.” On the issue of whether “federal government spending should be shifted to environmental programs from other areas,” 33 and 70 percent of the NEETF and TFCW respondents, respectively, disagreed with the statement. On the other hand, only 4 percent of TFCW respondents as compared with 58 percent of NEETF respondents believed that “the next 10 years are the last decade when humans will have the chance to save the Earth from environmental catastrophe.”

Summary

The NEETF study considered the relationships between level of environmental knowledge and environ-mental beliefs in some detail. Individuals with higher levels of education were generally more knowledgeable about environmental issues. Individuals with a high level of knowledge about environmental issues had beliefs about environmental laws and regulations that were somewhat closer to the beliefs of the TFCW respondents than individuals with a low level of environmental knowledge. Similar relationships also existed with respect to beliefs about environmental solutions.

Although agricultural producers may often feel they bear the brunt of environmental protection, they should be supportive of environmental education programs for the general public. Such educational programs can result in a more informed public. Greater environ-mental knowledge is associated with beliefs that economic development need not be sacrificed in order for the environment to be protected. How-ever, agricultural producers must be aware that if a difficult choice between the environmental protection and economic development must be made, most Americans favor environmental protection.

* Appreciation is expressed to Lynn M. Musser, a former Purdue faculty member, who worked with the National Environ-mental Education and Training Foundation (NEETF) in conducting the national survey. She provided the questions used in the survey and analysis of the NEETF results