Farm Bill Options and Consequences

March 13, 2002

PAER-2002-2

Allan Gray, Assistant Professor and Otto Doering, Professor

Why is U.S. agriculture singled out for special treatment in the form of large income transfers and subsidies? Some reasons are that agriculture is at the mercy of weather and that food is a strategic good. In addition, much of the land for the U.S. is owned and managed by farmers, who are responsible for its stewardship, and this land is essentially a national resource. At the time of the great depression, when the federal government first became actively involved in agriculture, there was still a large rural population, and incomes in rural areas were 60% less than incomes in urban areas. The first farm bills were designed to relieve the extreme distress in rural areas. By its own assessment, the Roosevelt Administration’s early farm bills improved the health of commercial agriculture, but did not solve the problems of the more disadvantaged in agriculture or solve the problems of land degradation and unwise use of resources.

What did the ’94 Republican Congress intend with the reforms in the 1996 Farm Act? The 1996 Freedom to Farm Bill was to make U.S. agriculture more market oriented and wean farmers away from government support. The mechanism for this was declining fixed payments to farmers, based on participation and payments from previous programs. Farmers would not have their acreage restricted or have to plant certain crops to qualify for payments (thus, “Freedom to Farm”). The payments would decline slowly and be a transition away from the large payments historically given to farmers in years of low prices. If prices got extremely low, there would be “loan deficiency payments” for farmers to give income support and effectively bring up the price to a price floor for those bushels or pounds of a commodity the farmer produced.

However, Congress substantially lost its “free market” nerve. When the ’96 Farm Act was passed, commodity prices were high, and farmers got their fixed transition payments in spite of the high prices. When prices fell in the late 1990’s to extremely low levels and farm income plunged, Congress made emergency payments to farmers to maintain farm income. Prices are still low today. The question is, what do we do now for a new farm bill since “Freedom to Farm” is set to expire in 2002?

Where We Stand Now

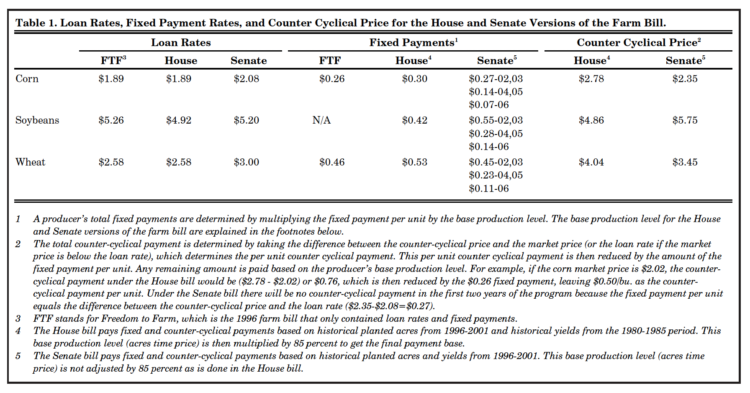

The House of Representatives passed a farm bill in October; the Senate passed their version of the farm bill in mid-February. The House and Senate bills are very similar for the commodity programs. Both versions of the farm bill continue the transition payments, maintain loan deficiency payments, and add a counter-cyclical payment or target price to further protect farmers when prices fall. Table 1 summarizes the key payment levels for corn, soybeans, and wheat.

Table 1. Loan Rates, Fixed Payment Rates, and Counter Cyclical Price for the House and Senate Versions of the Farm Bill.

The important differences between the two bills are that loan rates (used to determine loan deficiency payment levels) are higher under the Senate version, while counter-cyclical payment levels are higher under the House version of the farm bill. In addition, the Senate bill would allow producers to update their historical yield and planted acres based on the last five-years production, while the House would only allow acres to be updated, leaving yields at 1985 levels.

A long list of commodities would be included in a loan and loan deficiency program. Besides corn, sorghum, barley, oats, wheat, soybeans, minor oilseeds, upland cotton, and rice, also added, are wool, mohair, honey, dry peas, lentils and chickpeas. There would also be a special program for sugar, and peanuts would get cash payments to buyout quotas as peanuts begin being treated the same as other commodity crops. There would be a program for dairy, and regional compacts are still the contentious issue for this commodity. In addition, the House and Senate bills add substantial funds to existing conservation programs, helping bolster support from environmental groups.

As the House and Senate begin Conference Committee meetings, several differences must be resolved. Among the most contentious issues are the amounts of spending in the early versus later years of each bill, a more restrictive payment limit in the Senate version of the bill, and a ban on packers owning livestock that is also in the Senate version of the bill.

The House and Senate versions are budgeted at $170 billion over 10 years. However, the Senate bill is a five-year bill, which spends nearly $9 billion more in the first five years than the House bill. Many, including the administration, have expressed concern that the Senate farm bill spends too much money in the front years, and risks support levels in years 6 through 10 if commodity prices do not improve. However, Senate democrats argue that more help is needed in the early years given the depressed economic conditions of agriculture.

Late in the Senate debate on the new farm bill, an amendment was passed that reduced the payment limits for an individual producer to a total of $75,000 in fixed transition payments and counter-cyclative in southern states where higher value crops such as cotton and rice are grown. The House version of the farm bill contains traditional payment-limit language that has limits that are at least twice those in the Senate bill; if not more (depending on the structure of the farming operation). The public perception and political ramifications make payment limits an extremely contentious issue that lines up southern lawmakers against northern lawmakers irrespective of party lines. Important compromises will have to be made on this issue in the Conference Committee.

In another late amendment to the Senate farm bill, Senator Johnson from South Dakota introduced language that would make it illegal for packers to own livestock (except poultry) more than 14 days before slaughter. There are numerous sides to this issue, and the results could have major restructuring implications for the livestock industry. The Conference Committee will likely have compromises that deal with the ban on packers and the payment limits, but some restrictions with regard to both issues are likely to be in the next farm bill. (In a related article, the consequences of the ban on packer ownership of livestock are examined in more detail.)

What Are the Consequences of the Proposed Farm Bills?

Compliance with Trade Agreements: The House and Senate versions of the farm bill increase the level of government support for agriculture. Much of the increased support comes in the form of either counter-cyclical payments or increased loan rates. Either form of additional support jeopardizes the U.S. position in trade negotiations. The updating of bases is also contrary to the 1994 Uruguay Round agreement. The U.S. currently has a spending limit on “trade distorting” government support of just over $19 billion annually. Given the current economic conditions, spending limits may be breached, substantially degrading U.S. negotiating power in the WTO. Regardless of legality and whether spending limits are breached, either type of program is in opposition to the position the administration has taken in WTO negotiations. The negotiations have focused on reducing trade-distorting payments for all countries. Congress appears to be heading in a direction opposite of the way U.S. negotiations in WTO would like to see things move.

Production Incentives: The House and Senate versions of the farm bill both have mechanisms that trigger more support for producers when prices are low. The counter-cyclical and loan deficiency payments provided under both farm bills isolate the producer from the market signals contained in low prices. Low prices reflect the market’s opinion that stocks and production of a commodity are large. Therefore, the natural economic response would be to cut back on production, because the market does not “want” the commodity.

However, the price support mechanisms provided by the House and Senate versions of the farm bill send a different signal to producers. Rather than having producers respond to the market signals by curbing production (or more likely, by having the less efficiency producers go out of business or having some less productive land not farmed), the price supports and income subsidies signal to producers to keep producing the commodity despite low prices, which increases stock levels further reducing the price.

This strategy might make sense if the U.S. were trying to “outlast” its foreign competitors in a marketplace price war. However, the plan (which was started with the 1996 farm bill) has been very expensive to the U.S. taxpayer and has had little if any visible impact on competitors’ production levels or any expansion in long-term market share position in the trade of commodity products.

Distribution of Benefits: The House and Senate versions of the farm bill transfer large amounts of money to traditional program crops. The payments come in the form of direct payments not tied to production, price supports for current production levels, and income supports based on historical production levels. These various payments all contribute to supporting farm incomes and asset values for traditional program crops at substantially higher levels than without these payments. Nontraditional crops, like vegetables, fruit, and livestock, have not received support in the past (aside from some small emergency payments made to pork and apple producers). These nontraditional crops will not receive support under the new farm bill either. The administration would prefer to have a farm bill that was more inclusive of other agricultural products.

Land Value and Rents: The House and Senate versions of the farm bill would maintain or increase current land values and farmland rents. Land values are determined based on the income stream received from the land. As such, the income support provided in the House and Senate versions of the farm bill will likely be bid into land values and land rents in traditional program crop producing regions of the country. This can be a double-edged sword. For those producers who own the majority of their land and retired farmers who are renting their land, this increased land value support can be a big boon to their balance sheets and/or cash flow streams. However, tenant farms are likely to be in a worse position as rising rents squeeze out any margins gained by increased government support.

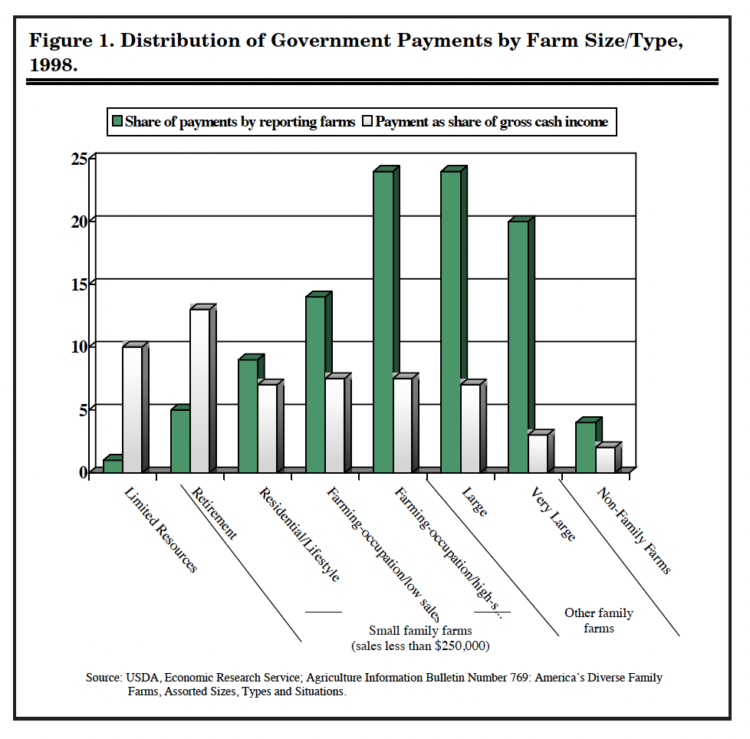

Farm Consolidation: The distribution of government payments to small versus large producers has been a hot topic lately. The general argument is that a relatively few, large farms receive the bulk of government payments under current farm programs. However, a recent publication by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service indicates that smaller producers, those with less than $250,000 in gross cash income, actually received as much or more government payments, as a percent of their gross income, as larger farmers did in 1998 (Figure 1).

The results of this study also suggest that government programs were more important in the financial performance of mid-size family farms. The House plan may maintain, or prolong at least, the current structure of production agriculture with respect to small, mid-size, and large producers by providing substantial income support and relatively more income support for mid-size family farm operations that may not have the economies of scale of large operations or are unable to find part-time off farm income. The Senate’s payment limit restriction would reinforce the results of the ERS report and reduce the support for the very largest farms, shifting more of the relative support to smaller and mid-size family farms.

Budget Costs: The House and Senate versions of the farm bill are budgeted at $170 billion over a 10-year period. However, these budget projections could be overly optimistic. Much of the budgeted cost is dependent on a baseline that forecasts considerable improvement in the economic situation for commodity production in later years. If this improved economic condition (i.e., higher prices) does not materialize, the actual cost of either the House or the Senate version could be extremely high. This is due to the counter-cyclical nature of the programs, where larger payments are made when farm economic conditions are “bad.” When economic conditions improve the payments under counter cyclical programs would decline.

Figure 1. Distribution of Government Payments by Farm Size/Type, 1998.

The basic assumption of the projected budget is that prices will be high enough in the later years (beyond year 4 of the farm bill) that counter-cyclical type payments would be almost non-existent. This is a particularly difficult assumption to make when considering that the payment mechanisms in both the House and Senate bills will encourage overproduction that will depress prices – unless an unforeseen weather event reduces production and stocks. Thus, it is likely that the actual cost of the farm bill could be much greater than $170 billion.

Concluding Thoughts

The House and Senate bills are essentially a continuation of current policies adding more support from old program mechanisms. Prior recipients, honey and wool, are added back in, and the peanut program is changed to more closely resemble other commodity programs. Little attention is paid to the foreign trade agreements, and substantial amounts are added to existing conservation programs. Both bills will maintain or enhance asset values, particularly land. The basic structure and impacts of these bills raise some basic questions.

How and to what extent does the public want to continue to support agriculture, and, within that, what groups in agriculture does the public want to support? The 1996 Farm Act made the income transfers to agriculture much more transparent than they were before. Information is readily available on both the government payment amount and the identity of the recipients. The House/Senate farm bill looks as though it will be extremely generous to agriculture. Will the public continue to believe that the need for the subsidies is real for those receiving them? Will other needs like social security and defense become more important so that such generous income transfers to agriculture lose public support?

Finally, what is it that agricultural really wants from a farm bill? Do farmers want to depend less on government and more on markets? Do farmers want higher market prices? DO farmers want free trade and competition? It seems clear that this farm bill will not deliver these things. This farm bill is designed to provide more government support for producers, insulating them from low market prices, removing the incentive to compete in world markets, and reducing the momentum for freer trade.