Farming in the 21st Century

November 18, 2007

PAER-2007-9

Michael Boehlje, Distinguished Professor and Bruce Erickson, Direct or Cropping Systems Management

Farming in the 21st Century is increasingly characterized by new business models and approaches to growth—changes which will require new management strategies for farmers. This discussion synopsizes the reasons for growth and consolidation of farming businesses and the management style these new farm businesses will require.

Farm Consolidation and Market Integration

Most U.S. crops are produced by family-based, relatively small-scale, and mostly independent firms. This had also been the case in previous years for U.S. livestock producers, but now that industry is dominated by larger firms more tightly aligned across the production and distribution chain. Poultry, dairy, and beef feedlot operations consolidated long ago, but pork has been more recent.

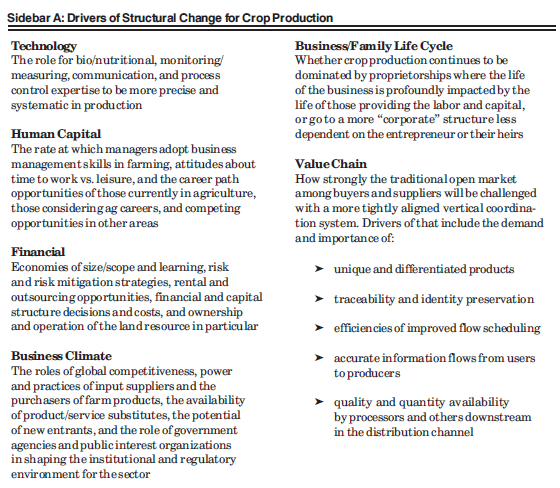

What about land-based agriculture—and particularly the commodity crops of corn, soybeans, wheat and cotton? Will they go through a similar transformation process, and as quickly as that experienced by the livestock industries? Other row crops such as potatoes and sugar beets have already experienced considerable consolidation and integration. To best predict, the fundamental drivers of consolidation and structural change must be identified and evaluated (see Sidebar A), and then compared to the general characteristics of today’s crop farming sector.

The convergence of four characteristics and management practices suggests a more rapid rate of growth in large crop farms than has occurred historically:

- Demographics and age of operators (not owners).

- Technology that modifies or releases timeliness constraints in crop production.

- New business models such as multi-site production that further alter production that further alters timeliness constraints in crop production.

- Increased use of the growth strategy of acquiring “businesses” rather than specific assets.

Age of Operators

Much discussion of structural change in agriculture has focused on the increasing age of farmers and the expectation that significantly larger amounts of farm property will be transferred to other owners as these farmers retire. But the transfer of ownership of farmland may not be nearly as important and immediate as the transfer of control/operation of that farm- land. Since almost 50 percent of U.S. farmland is rented (as high as 85 percent in some Midwest locales), changes in control and operation of farmland may not mimic changes in ownership.

In contrast to the past, it is not unusual today for a farm operator at retirement to control a substantially larger acreage than he or she owns. So in reality a larger proportion

of the total land becomes available to prospective operators than just that acreage owned

by the retiring farmer. Even though only two to three percent of farmland is transferred from the current to a new owner each year, the amount available for new operators each year is substantially more than that – maybe as much as 4-5% per year. Larger scale/more progressive growers, growers and especially growers who excel at relationship management

are probably better positioned to buy or rent this land.

Sidebar A: Drivers of Structural Change for Crop Production

New Technology

New technology has dramatically changed timeliness constraints that have been a significant limit on the growth potential for many grain operations. The ability to plant and harvest crops during the limited number of suitable field days in the spring and fall without encountering yield penalties is critical to overall efficiency and profitability. The development of guidance and auto-steer technology combined with larger planting and harvesting equipment (36 row planters and 12 row combines) has dramatically altered the timeliness constraint. For example, if planting 2000 acres in Illinois starting April 1 using a 24-row planter and working 12-hour days, there is about a 70% chance of finishing planting by May 1. If auto-guidance allows 16 hours per day and improves efficiency 5%, chances improve to 85%. With one 36-row planter and guidance, the chances of completion by May 1 exceed 90%.

More sophisticated monitoring and measuring technology that is part of precision farming also enables growth of operations. If crop production processes can only be monitored by people with unique skills, and hiring those skills or developing them in existing personnel is costly, the monitoring process limits the span of control to what one individual (or at least a few) can oversee personally. But if electronic systems can monitor the processes of plant growth (whether it be machinery operations, crop stage or development, or the level of infestation of insects or weeds), fewer human resources are needed for this task and generally larger scale is possible. Also, monitoring technology such as GPS or telemetry can allow more efficient management of employees through better work sequencing and scheduling, and reduce their workload through automating the capture and reporting of data. Electronic monitoring and control systems for crop production expand the span of control of a farmer/manager.

New Business Models

In addition to new technology and new operating procedures to relax timeliness constraints, farmers are also using management strategies and new business models to more fully utilize their machinery and equipment. One of those strategies is multi-site production. Krowers are increasingly producing in more than one locale, and in many cases are choosing those locales based on both weather patterns and transportation/logistics capacity and systems. They then move equipment from site to site, in essence allowing them to not just increase the utilization and lower the cost of machinery operations, but to again relax the timeliness constraint on size of operation without investing in additional machinery or equipment.

Another newer business model for many growers is the use of operating leases or machinery sharing to cost effectively acquire additional machinery services. Such arrangements have typically been individual agreements between growers and machinery owners (sometimes dealers, sometimes other growers), but increasingly these arrangement are developing through more formalized custom farming agreements or with such entities as Machinery Link that provide operating leases for combines, cotton strippers and power units similar to rental arrangements for automobiles, trucks and other equipment.

Precision farming combined with creative ways to schedule and sequence machinery use including 24 hour-per-day operations, moving equipment among sites and deployment based on weather patterns has the potential to increase machinery utilization and lower per acre machinery and equipment costs as well.

Growth Strategies

Finally, more and more of today’s expanding crop farmers are adopting the common business strategy of mergers and acquisitions compared to buying assets as in the past. Thus, farmers are buying businesses or acquiring the package of assets (including leased land) rather than purchasing individual parcels of land or pieces of equipment. And in fact, an increasingly common growth strategy for some growers is to approach a current operator with say 1000 to 1500 acres of farmland, who is near retirement, offer to buy the “farm business,” and retain the current operator and his/her machinery to complete the machine operations on that acreage. In essence, the acquiring farmer obtains control of not only the owned but also the rented acreage of the current operator, and also increases his capacity to farm this additional acreage by out- sourcing some of the machine and other operations to a skilled farmer who likely is uniquely qualified to farm that particular acreage. This strategy of acquiring businesses rather than acquiring assets usually involves obtaining control over a larger asset base, and thus accelerates the rate of growth and consolidation of large-scale operations.

The New Management Model

A consolidation and integration of row crop enterprises similar to that which occurred in the livestock sectors of agriculture dramatically alters the growth opportunities and strategies for farm businesses. Some of the most fundamental changes are in how crop producers view the availability and utilization of agricultural resources, growth strategies, and their role in the management scheme.

Shifts in How Resources are Utilized

The traditional farm business has sourced its labor, capital and management resources as a bundled package—all of these resources historically have been embodied in the family farmer.

In essence, the producer and his family members not only provided all of the money to finance the business (combined with modest amounts of debt), but did almost all of the work and made most of the decisions. But that bundled approach to providing resources for farming is changing to a new model where more of the labor is being hired, a broader capital base including outside investors and rented assets is being utilized, and in some cases even some management skills in the form of machinery maintenance managers or crop foremen are being hired.

Growth Not Always Incremental

Many farm businesses are growing at a rapid pace, and if the opportunities become available

a farming operation might grow dramatically in size with very few steps, for instance adding 900 acres to a 1500 acre base. These aggressive expansion strategies in many cases exceed the sustain- able growth rate of the business during the growth phase, and thus require the rebuilding of working capital and a reduction of the leverage position before

the next growth spurt can be absorbed financially.

As noted earlier many expansion/growth opportunities will be in the form of mergers and acquisitions of existing businesses rather than simply adding a facility of increment to the land or livestock base of the current farming unit. These merger and acquisition types of growth opportunities present new challenges as well as opportunities compared to the more familiar stepwise growth. These challenges include:

- A larger resource commitment

- Shorter and often steeper learning curve to reach efficiency goals of the larger business

- Inherited problems/challenges of the acquired unit

- Resource redundancies from merging similar types of businesses

- Different work styles of cultures of the people involved in the previously independent business units

These situations are common in merger and acquisition activity outside of production agriculture, and producers can learn from the successes and failures of mergers and acquisitions in other industries.

A New Role for Farmers

Most farmers excel at technical skills—the ability to use tools, techniques, and specialized knowledge to efficiently carry out production. While technical skills will still be important, the new management model for farmers requires more human and conceptual skills. Human skills relate to the ability to function well in inter-personal relationships. Conceptual skills

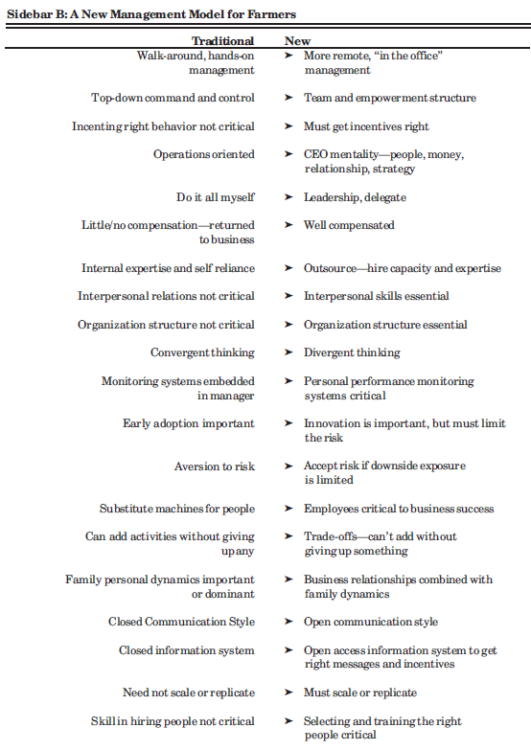

involve the ability to analyze and diagnose complex situations – drawing heavily on the analytical, creative, and intuitive talents. The new model is more of a general business manager rather than a plant or operations manager (see Sidebar B).

Sidebar B: A New Management Model for Farmers

Change Creates Opportunity

A desegregation or separation of resources, as well as the exits from agriculture, will result in unique and possibly unprecedented opportunities to rent land, provide custom farming

or other machine operating services, buy/operate/manage livestock facilities, pursue farming careers in foreman or other management positions, and to align and/or integrate in the value chain.

Managing the growing farm business requires a new skill set and a different style of management than most farmers have experienced during their farming careers. Developing this skill set will not be easy for many because of the abstract nature of the concepts and tasks involved. For those who are able to do so, growth will be more an opportunity and less a challenge.

A Final Comment

The rate of consolidation to larger size and scale crop farms is expected to accelerate in the next decade as new technology and management practices are adopted by grain farmers. And lenders and the capital markets will reinforce these trends as they fund those growers who adopt strategies such as multi-site operations, machinery sharing and other techniques to manage the operating risk and improve efficiency. Like livestock operations, grain farming in

the future will likely move to a more consolidated industry with large scale farms increasingly dominating the industry. To be successful in this new farming regime, farmers must transform their management focus from operations to strategy, from being a plant manager to a CEO.

For More Information

Dobbins, C., M. Boehlje, and A. Miller. Farmers as Plant Managers & Keneral Managers: Which Hat Do You Wear? ID-236, Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University. http:// www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/ID/ ID-236.html

Boehlje, M., C. Dobbins, and A Miller, 2000. Checking Your Farm Business Management Skills. Farm Business Management for the 21st Century. ID-23F, Purdue University Extension. http://www.ces. purdue.edu/extmedia/ID/ID-23F.pdf

Boehlje, M., C. Dobbins, and A Miller, 2001. Are Your Farm Business Management Skills Ready for the 21st Century? Self-Assessment Checklists to Help You Tell. Farm Business Management for the 21st Century, ID-244, Purdue University Extension. http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/ID/ID-244.pdf