Financial Vulnerability in the Current Downturn: A Stress Test of Midwestern Corn-Soybean Farms

June 15, 2017

PAER-2017-05

Authors: Michael Boehlje, Distinguished Professor of Agricultural Economics and Michael Langemeier, Professor of Agricultural Economics

The agricultural sector is facing uncertainty from many directions. These include global supply and demand uncertainties, evolving biofuels policies, trade uncertainties, exchange rates, interest rates, and geopolitical conflicts, among others. Any of these could make farms vulnerable to financial erosion, or even financial failure.

Given these increasingly complex and worrisome uncertainties, the admonition of Nassim Nicholas Taleb of Black Swan fame should be remembered. “Black swans” which are highly unlikely but critically significant events cannot be predicted, so the focus should be on positioning a business to maintain resiliency and reduce vulnerability should the bad event arise. In that spirit, this article will focus on the implications of the current and future uncertain market and financial conditions on the resiliency and vulnerability of Midwestern farms.

The Financial Situation

The U.S. farming sector exhibited very strong financial performance during the 2007-2013 period in terms of cash flow, high incomes, debt servicing, and equity accumulation. However, that strong performance has been accompanied by increased volatility. This increased volatility is a result of wide fluctuations in crop and livestock product prices, input costs and to volatile production due to both more variable yields in crops and losses from disease such as avian influenza and PED in hogs. That has created more operational and financial risk for farm businesses. Even though the variability of prices as a percentage of the average price has not changed much compared to the past, higher costs and the fixed nature of some of these costs has increased the variability of both operating margins and net income on both an absolute and relative basis dramatically.

The amount of financial leverage (debt relative to equity capital) in the industry generally declined from 1990 to 2013, with debt-to-equity falling to a low near 13% in 2013. This suggest that debt servicing risk for the sector is less than it was, for example, in the l 980’s. However, after 2013, farm debt has once again been rising relative to equity reaching 16% in 2017 (USDA). While debt levels are still modest sector wide, industry averages do not accurately reflect the true financial risk for individual farms. Larger scale farmers who have been growing rapidly have leverage positions more than double the industry average (Hoppe and Banker, 2010). Also, “shadow bank” financing in the form of loans and leases from captive finance companies (for example Deere Financial Services) and merchant and dealer credit from input suppliers is not well documented and is likely to be under-reported in the widely referenced USDA data.

Low interest rates are another factor that may be masking the dangers of debt servicing capacity. Interest rates on debt have been abnormally low. Rising rates will increase the debt servicing requirements for farmers who have not converted from variable to fixed rate loans. In addition, operating credit lines have increased for many producers, and interest rates on these loans are reset at renewal, and t h u s will increase when market rates rise.

Debt servicing ability can also be impact by high cash rents. Some farmers have signed longer term (3 year), high fixed rate cash rent leases to obtain control of land rather than purchase that land. These arrangements result in fixed cash flow commitments irrespective of productivity and prices much like a principal and interest payment on a mortgage. Farmers are also facing more strategic risks than they have in the past such as disruptions in market access and in supplier relationships including the possible loss of a lender, loss of landlords, regulatory and policy changes, food safety disruptions, and reputation risk, etc.

U.S. agriculture is notorious for its boom and bust cycles. Strong global food demand and robust biofuels markets strained global production capacity during the 2007-13 period. The prospects of tight global supplies spurred booming farm incomes. Historically low interest rates quickly capitalized these high incomes into record high farmland values. But as with past booms, the prospects of a permanent “golden era” in agriculture quickly faded. High farm incomes stimulated world production and the promise of global demand growth rates weakened resulting in low agricultural commodity prices and incomes. These leaner farm incomes were unable to support the record-high farmland prices. As a result, many farmers that thought they were seizing the emerging opportunities may be left empty- handed as market and financial conditions have changed.

Consequently, farmers, lenders, policy makers, and the academic world are asking many “what if” questions: What if commodity prices continue to be depressed? What if seed prices don’t go down more; or cash rents don’t adjust? What if land values decline further? With all the “what if” questions in mind, farmers and economists are concerned about the incidence and intensity of financial stress the farming sector might encounter in the future

Stress Test: How Many Farms Are Vulnerable?

To obtain some insight into these questions, the financial performance of various Midwest grain farms with different size, ownership status, and capital structures were examined under the shocks of volatile crop prices, yields, fertilizer prices, farmland value, and cash rents (Boehlje and Li, 2013). Monte Carlo methods were used to generate simulated crop prices and yields, fertilizer prices, farmland value and cash rents. The farms were of three sizes 550, 1200, and 2500 acres. They had three different ownership levels of 15%, 50%, and 85% with the remainder cash rented. Finally, they had two capital structures as measured by their debt-to-asset ratios of 25% and 50%.

The data used to estimate these distributions come from historical observations for the period 1970 to 2010. The Monte Carlo technique randomly draws values from the historical distributions to populate a financial budgeting model which generates financial projections for a three-year period. This budgeting activity was conducted 1000 times which resulted in distributions of possible financial outcomes that are driven by the distributions of price, yield, farmland value, and cash rents as the drivers of the financial outcomes. Various financial measures and ratios generated by this model were used to evaluate the income, cash flow, debt servicing, and equity position of the various farm situations.

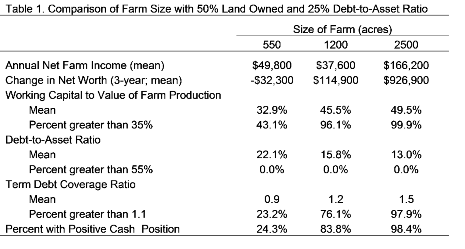

Given 50% land ownership and a 25% debt-to-asset ratio, the percentage of farms that have a positive cash balance after meeting all the financial obligations and family living expense increases with farm size (Table 1). Unfortunately, only 24% of the smaller farms (550 acres) have a positive cash position by the end of the three-year period. Larger farms have better profitability measured by net farm income and operating profit margin ratio, as well as lower volatility of these measures. At the end of the three-year projection period, larger farms have a higher average working capital to value of farm production (WC/VFP) ratio, and a higher percentage of farms with the WC/VFP ratio exceeding 35% was 99.9% for the 2500 acre farms compared to just 43.1% for the 550 acre farms. Repayment capacity, as measured by the term debt coverage ratio (net farm income divided by annual term debt principal and interest payments), is also higher for larger farms, with a mean value of 1.5 and 97.9% of the time they exceeded the underwriting standard of 1.1. The 550 acre farms had a mean value of 0.9 and only 23.2% of the time exceeded the1.1 standard.

These results suggest that smaller farms with one-half or more of their farmland rented and with modest leverage of 25% debt-to-asset ratio as is typical of young farmers, are highly vulnerable to price, cost, yield, and asset value shocks.

Large farms often have some advantages in terms of volume of production and in spreading fixed costs over large output. In this study, larger farms show superior financial performance and resiliency, but there are some important additional reasons why. In the model, family living expenses are assumed to be the same for both size farms, and thus the income available after these family expenses is much lower for smaller farms. Another model assumption was that no off-farm income was available to supplement any of the farming businesses. Thus the funds available for debt service on these smaller farms is much less, resulting in working capital, cash flow, and debt service problems. In reality, small farms often supplement family living expenses with off-farm income or have other farm enterprises such as livestock or specialty crops.

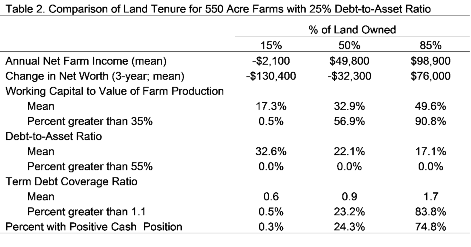

Different land ownership arrangements have a dramatic impact on the vulnerability of the smaller (550 acre) farming operations (Table 2). Those 550 acre farms with 85% of their land owned not only have substantially higher incomes than those who rent a higher proportion of their land, they are also able to accumulate additional equity over the three- year period ($76,000), reduce their leverage position to 17.1%, and have strong working capital and cash positions. In contrast, farms with only 15% of their land owned have negative net income ($2,100), lose equity ($130,400), increase their leverage position to 32.6%, and have a very weak term debt coverage ratio of 0.6 with almost no chance (0.5%) of being greater than 1.1. The farms that rent a large proportion of their land are very vulnerable to financial stress from price, cost, yield, or asset value shocks even with crop insurance and hedging strategies in place.

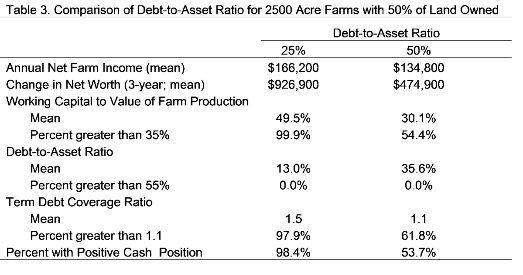

Table 3 compares financial characteristics of 2500 acre farms with 25% and 50% debt-to-asset ratios. Increasing the leverage from 25% to 50% reduced income only modestly from $166,200 with a 25% debt-to-asset ratio to $134,800 with a 50% debt-to-asset ratio. The change in income when more debt is used is the result of higher interest cost. In addition to lower income, the farm with a higher leverage position has lower net worth accumulation and cash flow. Even with a higher initial leverage position, these farms still have relatively strong working capital, debt servicing, and cash positions. Thus, larger farms, as characterized in this study, have only modest vulnerability to higher leverage positions and are more resilient to shocks in prices, costs, yields, and asset values.

These “stress test” results suggest that the financial vulnerability and resiliency of Midwest grain farms to price, cost, yield, and asset value shocks are dependent on their size, ownership tenure, and leverage positions. Farms with modest size (550 acres) and with a large proportion rented are very vulnerable irrespective of their leverage positions. These same modest size farms are more financially resilient if they own a higher proportion of their land. Large farms with modest leverage (25% debt-to-asset ratio) that combine rental and ownership of the land they operate have relatively strong financial performance and limited vulnerability to price, cost, yield, and asset value shocks. In addition, these farms can increase their leverage from 25% to 50% (in this study) with only modest deterioration in their financial performance and a slight increase in their vulnerability.

Just because the entire agriculture sector is still in an overall strong position with debt-to-asset ratio of 14% (USDA, 2017) this study shows that some common farm types are vulnerable to price, cost, yield, and asset value shocks and that cash flow and debt servicing problems are going to continue and may grow depending on the direction of the agriculture economy.

Eroding Financial Position: The Lender Responds

What insights does this “stress test” analysis provide concerning the current downturn? How might future events evolve that would create a 1970’s-80’s boom-bust cycle?

U.S. farm debt accumulation has not accelerated in the last decade as it did during the 1970s. But the distribution of debt among farmers is important. Recent analysis of the financial condition of farmers indicates that those who are younger (less than 35 years of age) have significantly higher debt loads and debt-to-asset ratios than the industry average (Briggeman 2011; Ellinger 2011). As indicated earlier, larger and rapidly growing farmers are more highly leveraged than the industry average. The real risk is that these farmers are currently losing money and consequently burning up working capital or borrowing to cover operating losses, which reduces their financial resiliency.

Similar to past farm booms, low interest rates fostered the capitalization of rising farm incomes into record high farmland values. Accommodative monetary policy by the Federal Reserve pushed nominal interest rates to historic lows. The surge in U.S. farmland prices outpaced the rise in cash rents. In fact, the average price-to-cash rent multiple, which is similar to a price-to•earnings ratio on a stock, surged to a record high of over 30 in various Corn Belt states (Langemeier et al., 2016).

The potential for higher interest rates also present a future risk. Higher interest rates have two distinct impacts on U.S. agriculture (Henderson and Briggeman, 2011). Rising interest rates place upward pressure on the dollar, which trims U.S. agricultural exports, farm profits, and farmland prices. In addition, higher interest rates also boost the capitalization rate, which weighs further on farmland prices. The impacts are compounded on highly leveraged farms as higher interest rates reduce incomes and raise debt service burdens, as the 1920s and 1980s demonstrated.

When land values were rising, farmers were aggressive land buyers not only to acquire the income from that land, but also to capture the wealth effect of anticipated higher land values. That wealth effect did not just show up in land purchases but also in purchases of more machinery and facilities because of their stronger financial positions. These purchases were often made by larger growth-oriented farmers who had higher leverage positions.

Even if they had sufficient cash to make sizeable down payments, these transactions have changed the structure of the balance sheet by reducing current assets while increasing non-current assets, and adding to current liabilities by the amount of the annual principal and interest debt servicing requirement. Thus, the liquidity position of the business as defined by working capital or the current asset/current liability ratio was reduced, making these firms more vulnerable to income shocks.

At the same time, farmers who are expanding rapidly have also been aggressive bidders in the land rental market. High and fixed cash rental arrangements have become increasingly common and some of these agreements are for multiple years (2-3 years) at relatively high fixed rates. These high multi-year cash rents result in increased future fixed cash costs much like mortgage obligations on land debt. These “pseudo-debt” financial obligations are typically not reported on the balance sheet, but they are similar to capital lease obligations which increase the leverage and typically reduce the working capital/liquidity position of the business.

During the boom, strong cash positions and concerns about high tax liabilities resulted in significant purchases of depreciable machinery and equipment, which moved assets from the current to non- current category without restructuring the liabilities, thus creating an additional imbalance in the balance sheet. Low crop prices and weak operating margins have more recently caused larger operating lines, which increases leverage and further reduces liquidity.

This increasingly misaligned balance sheet with a higher portion of current vs. non-current liabilities increases the vulnerability of the business to income shocks from lower prices, lower yields, or high costs. Such shocks decrease margins and cash flows as well as inventory positions, and could quickly result in a working capital position below lender underwriting standards. A typical lender response in this situation is to suggest liquidating inventories and using the proceeds to reduce operating debt. However, for farmers who file Schedule F tax returns, this could trigger significant tax obligations since the tax basis on raised grain and livestock for Schedule F tax-filers is zero. Thus, the full proceeds at sale are taxed as ordinary income which reduces the liquidity position even further.

An alternative lender response is to restructure the debt and move some of the current obligations to non-current using the appreciated value of farmland as security. This approach results in leveraging the capital gain in farmland – the leverage effect of capital gains. During the boom, lenders often resisted increasing loan to value ratios on farmland purchases but are now encouraged to monetize capital gains in land by extending additional credit based on the higher land values. Higher land values and the resulting increased equity positions would appear to provide adequate security and secondary repayment capacity to support the larger debt load, but what if land values continue to decline? Clearly, the debt per dollar of revenue generated from the land will be higher if price declines and what if lower incomes are permanent rather than temporary. The business is now very vulnerable to further income shocks or asset value deterioration – the working capital position has been destroyed and credit reserves have been fully used. Permanently lower incomes and/or higher interest rates will not only create debt servicing problems, but also reduce the discounted cash flow and thus weaken the demand for farmland.

Summary: More Farm Adjustments to Come

U.S. net farm income is projected to drop for the fourth consecutive year in 2017 (USDA). More importantly total sector income in 2017 is expected to be only one-half of the record 2013 level. Farmland values in Indiana declined by 11.7% between 2014 and 2016, with the 2017 results to be published in the August 2017 Purdue Agricultural Economics Report, (Dobbins and Cook, 2016). Surveys from the Federal Reserve Banks indicate that land values in the Corn Belt continue to show generally softer values, and debt servicing challenges are increasing.

“Stress-test” results reported here suggest that the financial vulnerability and resiliency of Midwest grain farms to price, cost, yield, and asset value shocks are dependent on their size, ownership tenure and leverage positions. Farms with modest size (550 acres) and with a large proportion of their land rented are very vulnerable irrespective of their leverage positions unless they have significant income from off-farm sources or livestock or specialty crop enterprises. These same modest size farms are more financially resilient if they own a higher proportion of their acreage and therefore rent a small portion. Larger size farms (2500 acres) with modest leverage (25% debt-to-asset ratio) that combine rental and ownership of the land they operate have relatively strong financial performance and limited vulnerability to price, cost, yield, and asset value shocks.

Our results suggest that the statement that farmers are resilient to price, cost, yield, and asset value shocks because of the current low use of debt in the industry (currently a 14% debt-to-asset ratio for the farming sector) does not adequately recognize the financial vulnerability of many typical family farms to those shocks. Not nearly as many farm families are expected to have to sell assets or face bankruptcy compared to the 1980s bust, but many will still face cash flow and debt servicing problems and will need to make major adjustments to reduce their costs or extend their loan repayment terms.

References

Boehlje, M. and S. Li. “Financial Vulnerability of Midwest Grain Farms: Implications of Price, Yield and Cost Shocks.” Staff Paper #13-1, Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University, July 2013.

Briggeman, B.C. “The Importance of Off-Farm Income in Servicing Farm Debt.”

Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, First Quarter 2011, pp. 83-102.

Dobbins, C. and K. Cook. “Indiana Farmland Values and Cash Rents Continue Downward Adjustments.” Center for Commercial Agriculture, Purdue University, August 2016.

Ellinger, P. “Weathering Unexpected Downturns in Agriculture.” Proceedings of the 2011 Agricultural Symposium, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, July 2011.

Henderson, J. and B.C. Briggeman. “What are the Risks in Today’s Farmland Market?” The Main Street Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Issue 1, 2011.

Hoppe, R.A. and D.E. Banker. “Structure and Finances of U.S. Farms: Family Farm Report, 2010 Edition.” USDA-ERS, EIB-66, July 2010.

Langemeier, M.R., T. Baker, and M. Boehlje. “Trends in Land Prices, Cash Rents, and Price to Rent Ratios for Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana.” Center for Commercial Agriculture, Purdue University, August 2016.

USDA-ERS. “Highlights from the February 2017 Farm Income Forecast.” www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-sector-income-finances/highlights-from-the- farm-income-forecast.