Gains For Agriculture In the GATT Agreement

January 18, 1995

PAER-1995-01

Philip L. Paarlberg, Associate Professor

After more than seven years of negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) an agreement was reached and approved by both houses of Congress. This article examines what was accomplished in the process of negotiating the agreement and what benefits it offers the United States.

Contents of the Agreement

The original U.S. proposal suggested that all production and trade distorting subsidies in agriculture be ended by the turn of the century for all GATT members. Nations wanting to support their agricultural sectors could do so with transfer payments not tied to agricultural output. The U.S. proposal was based on the belief that free trade achieves the greatest economic efficiency, and thus maximizes the benefits from trade. Since U.S. farmers are efficient low-cost producers, they could compete in a global environment and gain from agricultural trade liberalization.

While some nations, such as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, and Canada, shared the objectives of the United States, many countries did not. Opposition to the United States’ position came from the European Union (EU). The EU sought a GATT agreement that would leave countries free to set their domestic policies without considering the impacts on other nations. The EU also wanted to limit the degree to which import barriers would be reduced, and to set minimum export market shares and prices. Given such diver-gent objectives, it is not surprising that negotiators took years to find common ground.

In the final text both sides compromised. The cuts in agricultural subsidies of around 20 percent from the 1986-1988 base period are far less than the complete phase-out requested by the United States. The same is true for market access. The United States wanted a full liberalization, but in the end import barriers are converted to tariff equivalents and cut 36 percent with minimum access guarantees in some cases. Elimination of export subsidies was a major objective of the United States. While export subsidies are not ended, they are sharply reduced. Using a 1986-1990 base period, export subsidy expenditures are to be lowered by 36 percent and the volume of subsidized exports by 21 percent.

The European Union compromised as well. Domestic programs were included in the treaty and are reduced. The Euro-pean Union agreed to convert import barriers to tariff equivalents which are to be cut. Export subsidies are offered by the EU on a wide range of farm goods and these must be scaled down. The original EU view of a managed world farm trade with specific minimum export shares and prices is not included. Nor can the EU adjust its tariff structures to escape its previous GATT commitment to import oilseeds and meals duty-free.

Benefits to the United States and Indiana

The GATT agreement and its process of negotiation are important to agriculture. One reason is that the expansion of world trade which has occurred since World War II and which contributed to world prosperity is furthered by the agreement. A failure to achieve an understanding in the present round of negotiations would have led to increased protection and trade wars. This would have harmed all nations and been especially harmful to export sectors like U.S. agriculture. The decline in U.S. agricultural exports in the early 1980s contributed to the financial stress experienced by U.S. agriculture at that time. The GATT agreement helps keep protectionist pressures at bay.

Another benefit from this agreement is that agriculture has been included. Previous rounds of GATT negotiations have generally excluded agriculture while greatly liberalizing non-agricultural trade. Agricultural commodities are now among the goods most restricted by trade barriers and manipulated by export subsidies.

Furthermore, the agreement recognizes the linkage between domestic farm policies and trade. Trade policies in agriculture flow from the type and level of farm sup-port policies so that the costs of domestic farm programs are partly paid by foreign nations. In the cur-rent agreement, domestic farm policies are included in an effort to reduce the international costs of farm programs. While the cuts in subsidies are not large, a precedent is set.

In a sense the negotiations have already accomplished much as many nations have already undertaken farm policy reforms consistent with the agreement. In May 1992, the European Union adopted a farm pol-icy reform in which the type and magnitude of changes reflected the influence of the GATT negotiations. Without the GATT round the EU would have adopted a much different set of farm policy changes. In 1985 and 1990, U.S. farm legislation moved in a direction consistent with the GATT negotiations. Given the changes introduced, the United States already meets most of the cuts required by the agreement. The Japanese began opening their market for agricultural goods and the GATT negotiations played a contributing role. In the late 1980s the Japanese began to liberalize imports of beef, orange juice, and many other agricultural goods. They have announced the beginning of liberalization for rice imports. South Korea also has said that it will begin to liberalize rice imports due to the GATT agreement.

The GATT negotiation process created pressure for reform and the final agreement affected the timing as politicians cited the GATT agreement as the cause of reform.

While the negotiations promoted policy reform, ratification of the final agreement is also important. Previous policy reforms can be undone. Ratification preserves the policy changes, since policy reversals would violate international commitments and be subject to trade sanctions. Ratification brings gains to U.S. and Indiana farmers.

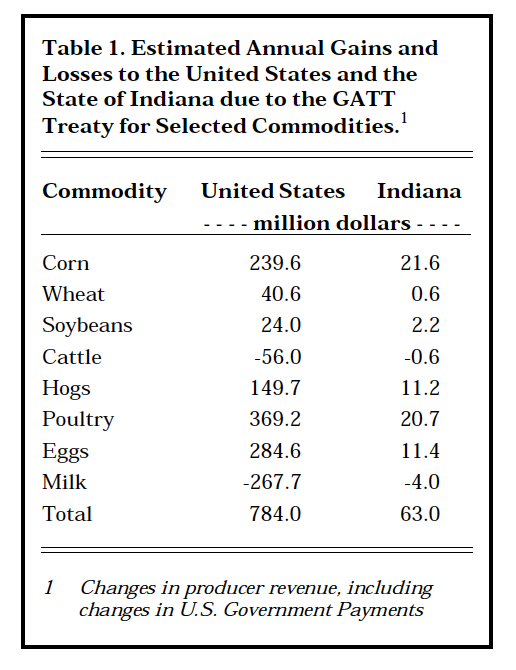

My estimate of the gains for farmers in the United States are $784 million per year. The largest gains are in poultry ($369 million); eggs ($285 million); corn ($240 million); and hogs ($150 million). While not as large in magnitude, gains are also positive for wheat and soybeans, (Table 1).

Table 1. Estimated Annual Gains and Losses to the United States and the State of Indiana due to the GATT Treaty for Selected Commodities

My estimated gains to Indiana agriculture, after full implementation, are about $63 million per year (Table 1). These gains occur for most commodities produced in the state. For corn producers, revenue and government payments should rise almost $22 million, while soybeans earn $2.2 million more. Hog, poultry, and egg producers should see significant increases in producer revenues. Some losses might be experienced by cattle and milk producers as import restrictions are eased. The loss for cattle producers would be very small. A somewhat larger loss could result for milk producers (-1.3 per-cent) as Section 22 import restrictions for dairy products are relaxed. Whether that occurs depends on whether the Commodity Credit Corporation buys the additional imports as it has that authority. It should be noted that these estimates exclude the value of policy reforms already made which reflected an anticipated GATT agreement so that the gains are larger than those generated from the final agreement alone.

Conclusion

The GATT agreement required over seven years of negotiations to reach its final form. It is not the com-prehensive liberalization of world trade originally sought by the United States. Yet world agricultural trade has become more liberalized and the agreement offers additional benefits. It provides a barrier against further increases in protectionism in world trade and will help expand world incomes. Agriculture is included in the agreement and domestic farm policies must be made subject to GATT rules. Governments will be less able to protect inefficient producers. Future rounds will not have to fight to put these two items on the agenda for further liberalization.

In addition, the GATT process has affected many of the farm policy reforms which have occurred since the round was launched in 1986 and these reforms have improved the trade outlook in agriculture. A ratified agreement locks these reforms in place. The agreement will also provide gains from reforms which still must be implemented to be consistent with the final agreement. For U.S. farmers these gains are estimated to be$784 million annually, and around$63 million for Indiana farmers.