Global Warming, A Perspective for Indiana Agriculture

September 12, 1998

PAER-1998-13

Otto Doering, Professor

There has been a lot of hot air generated about global climate change, but very few specifics about what impact it may actually have on us in the future. We really need to consider two distinctly different kinds of impacts. First, there is the direct impact of climate change — the actual change in temperature and other climate factors that may be of direct concern to agriculture. Second, there are the impacts of those things we do in reaction to climate change— things like the carbon reductions planned under the Kyoto accord. For most of the U.S. economy, trying to reduce carbon emissions will have initial greater impact than the actual climate changes that might begin to occur.

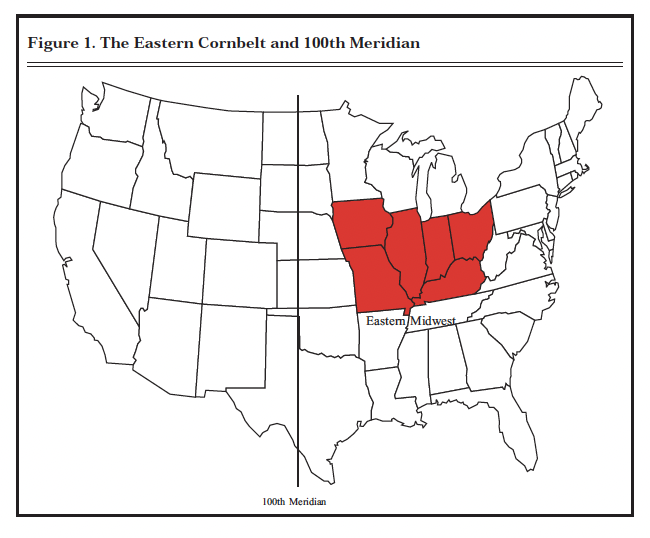

U.S. agriculture is in a different position from most of the rest of the economy. Temperature and rainfall are critical, and we are not just talking about amounts, but also about distribution and frequency. If we look at a map of the central U.S., the breadbasket of America, there are two critical gradients (Figure 1). Temperature gets cooler from the warmer South to the cooler North, and rainfall tends to decrease from the Eastern Cornbelt as we move from Ohio and Indiana through Iowa into western Nebraska and Kansas. When we hit the 20-inch rainfall line at about the 100th meridian, the crop mix changes, and we see more in the way of dryland crops. Global climate change has the potential of changing the location of the 20-inch rainfall line and/or changing the character of temperature and incidence of rainfall so that cropping patterns will shift at this critical margin.

Looking at the temperature gradient, if we go from south to north in the Cornbelt, temperature decreases, and we make choices about what we grow based upon this. Farmers in southern Wisconsin may be a little short of degree-days for top yields and are likely to be using short sea-son hybrids. As we go south there are more degree-days, longer season varieties prevail, and we are able to get into rotations like wheat/soybean double cropping. We also have different pest concerns to the north as compared to what we face to the south. The key question for us now is how climate change might upset the current pattern of agricultural activity on the land.

Overall, the areas that will likely have to change the most are the areas that are now fringe areas of climate, like the Western Cornbelt that is at the rainfall limit. The central Cornbelt, where so many conditions are so favorable to the corn/soybean monoculture, will be less likely to have to change cropping systems due to some deterioration of those excellent conditions.

For the last four years a group from Purdue, Indiana University, and the University of Illinois has been looking at what the impacts of climate change might be on Upper Midwest agriculture.

We have been particularly concerned about how farmers might adapt to climate change and maintain the profitability of their enterprises. If climate change were to involve just shifts in the gradient— a bit warmer or a bit dryer or wetter everywhere — then adaptation would be relatively straightforward. However, the climatologists have also talked about some climate changes that would be more unsettling.

- The warming in the Northern Cornbelt might be greater than the warming in the Southern Cornbelt.

- Warming will not be equally divided between summer and winter. Winter will warm more.

- Most important, there may be greater weather variability. July rainfall might be up 20%. But, more important, it might occur in two storms!

- Finally, the increased variability might result in “seasonal fuzzi-ness” — a less distinct boundary between seasons or more chance of late frosts in the spring and early ones in the fall, countering what might be a two-week increase in the growing season in the Cornbelt.

Figure 1. The Eastern Cornbelt and 100th Meridian

What such a future calls for is not a “Chicken Little The Sky Is Falling” approach. What is called for is thoughtful contingency planning for both the private and the public sec-tors. Chicken Little behavior does not make real world sense, contingency planning and risk management do.

A critical aspect of the contingency planning is time frame. The current wisdom from climatologists looks out 50 to 100 years for significant climate change. Within this time frame it looks as though genetics, pest control, management, and other strategies can bring about successful adaptation for agriculture. As pests move north and are controlled less by winters that are proportion-ally warmer, the industry believes that it can deal. If the time frame is shortened, to 10 or 20 years, the story would be different.

The time frame also has some-thing to say about who prepares for the contingency. The private sector needs payback on investment in a relatively short period and may be unwilling to risk investment today when the payback is in 50 years. On the other hand, if a change trend looks more certain and clear eco-nomic benefit can be derived from a new product or service, the private sector is likely to take the lead.

There is such a high public value in the stability of the food supply and the cost of disruption is so high, that there is an imperative for the public to invest as well, even on a contingency basis. Thus, we should expect the public sector, the Land Grant Universities, and the Agricultural Research Service to begin to think about coping with climate change well before it becomes attractive for the private sector to do so.

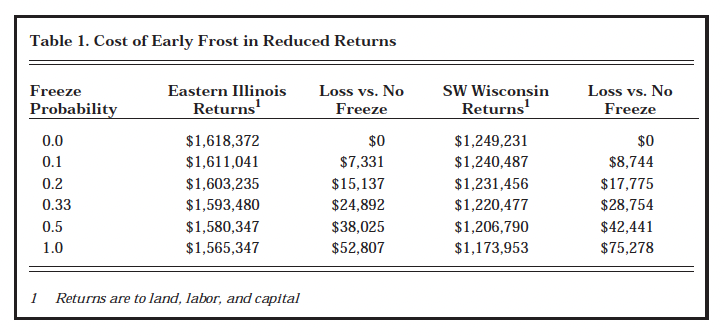

As an example of the kind of adaptation that may be necessary, consider the impact of variability that leads to seasonal fuzziness, in this case early frost. Table 1 illustrates the cost of different probabilities of early frost to a large corn/soybean operation in Eastern Illinois and another in Southwest Wisconsin. Note the drop in total returns may not look terribly large. However, the decline in actual profit would be a much greater proportion. A 0.20 probability of early frost carries with it approximately $25,000 of loss in Eastern Illinois and more in Wisconsin. This may actually be a third or a quarter of a farmer’s net income. The value of this loss is such that the private sector will ultimately have a real incentive to develop frost tolerant varieties, but a long-range effort is still required to make this genetic trait possible. As the probability of something like seasonal fuzziness changes, so changes the economics of successful adaptation.

Table 1. Cost of Early Frost in Reduced Returns

The conclusion is that there is a need to have concern about global climate change, but no need to panic. The kinds of costs like 50% decline in farm income that some people are talking about from government intervention are absurd. The concern may be best expressed in terms of contingency planning and good strategic management. Agriculture’s concern is probably best focused on climate variability and adaptation to the kinds of changes this might bring. There will be important roles for both the public and the private sector, and producers in their own best interests should encourage both private and public institutions to stay ahead of the curve on this issue.