Hog Production Booms In North Carolina: Why There? Why Now?

August 16, 1993

PAER-1993-14

Chris Hurt, Extension Economist, Purdue University and Kelly Zering, Extension Economist, North Carolina State University

North Carolina is in a hog production boom that has taken them from the status of a minor producer a few years ago to one of prominence among the states. And the boom is not over! To many in the corn and hog belt, it is a mystery why a state so far removed from corn production would think they can raise hogs profitably. Not many years ago, midwest hog producers scoffed at their fellow North Carolina peers; now many of them would stand in awe of the

“North Carolina production system.”

We have undertaken a six-month study of the North Carolina pork industry in an attempt to understand the reasons why the expansion is occurring there, and why it is occurring now. The reasons are many, and they are related to a unique set of people and circumstance that have come together in North Carolina. However, the implications are bigger than just North Carolina, because if their pork industry model is successful, it may provide a glimpse of the future for the national industry.

Now a Competitive Force

In production efficiency, North Carolina producers, as a group, have moved to the head of the class in many categories. They lead the nation in such measures as: pigs per litter; pigs per sow per year; productivity per animal in the breeding herd; and feed efficiency to name a few (Hogs and Pigs). They also lead the nation in the restructuring of the hog industry from small operations to much larger commercial size units that are specialized in hog production. In addition, they lead the nation in the movement toward more tightly coordinated arrangements between production and processing.

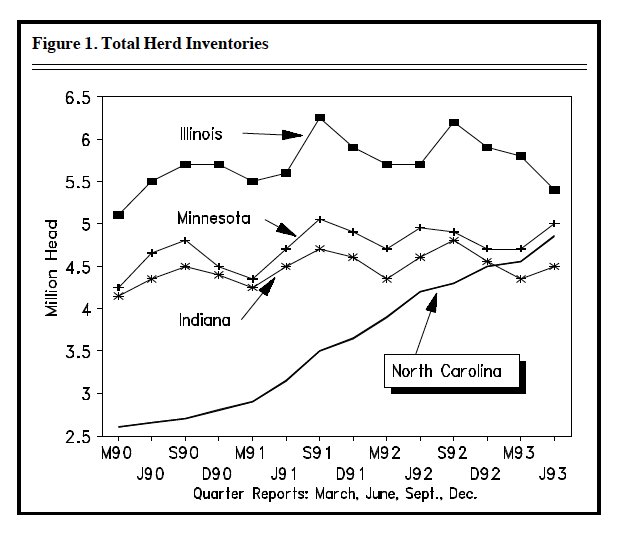

Figure 1. Total Herd Inventories

How big is the boom? In the past three years, North Carolina producers have added about 240,000 animals to the breeding herd. These added animals represent about 3.2 percent of the U.S. breeding herd and equal or exceed the total breeding herd inventories of three of the ten top production states: Ohio, 240,000; Kansas, 185,000; and Georgia, 150,000. The 240,000-head expansion in North Carolina’s breeding herd from June 1991 to June 1993 exceeds the expansion of the breeding herds in Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Indiana, and Nebraska combined. The latter five states have 56 percent of the nation’s breeding herd (Hogs and Pigs).

North Carolina has moved from seventh, in 1991, to fourth in total inventory. Along the way they have passed Missouri and, just this year, Nebraska and Indiana, as shown in Figure 1. We are projecting that North Carolina’s hog inventory will pass Minnesota in the September 1993 survey and will pass Illinois by the end of 1994, becoming second only to Iowa.

What Drives the Boom?

There are usually many reasons for a dramatic increase in production, but we believe the following are the key reasons. These are described in what we feel is their order of importance.

New Packing Capacity: The story starts with new packing capacity. North Carolina traditionally has shipped a large number of hogs to other states for processing. The primary receiving state was Virginia, and the packer there was Smithfield Foods, located just outside Norfolk. Smithfield Foods is growth oriented and has historically had high returns, having generated annual returns on equity in excess of 25 per-cent in the 1988-1992 period, (Standard OTC Stock Reports). Since the mid-1980’s, they have been trying to stimulate additional pork production in Virginia. Their hope was to generate 100,000 sows of added production in company-owned or controlled production. They were successful in reaching a portion of this total, but environmental regulation and citizen concern in Virginia during the late 1980’s caused them to abandon these goals.

Smithfield had already been buying many hogs from North Carolina, and they increasingly looked to these producers to increase production. They developed close working relationships with several of the larg-est hog producers, who also some of the largest hog farms in the world. Several of these hog farms were also interested in developing closer linkages with a packer. These relationships led to Smithfield’s decision to build a new processing plant closer to the production concentration in the southern coastal area of North Carolina.

What a plant it is! Processing began in the fall of 1992 at the largest capacity plant in the United States. If they are able to double-shift the plant successfully in 1994, it will process about 8 million head of hogs per year, or roughly 8.5 per-cent of the entire U.S. production. This number, if achieved, will exceed Indiana’s total production.

As a result of this massive increase in processing capacity, a number of North Carolina producers are in a rush to put hog production in place to “fill” this capacity.

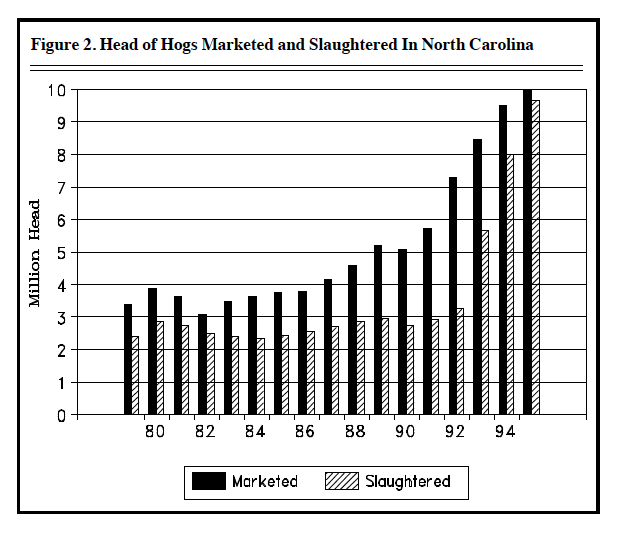

Figure 2 shows the number of hogs produced and slaughtered in North Carolina. The numbers for 1993 through 1995 are based on projections we have made from industry interviews. First, note the staggering increase in production which has already occurred. In 1986, the state marketed about 4 million head of hogs, and we are projecting a doubling of that number to about 8.5 million this year. Current expansion plans among key producers in the state, if realized, will thrust the production to around 10 million head by 1995.

Next, note the low number slaughtered in the state compared to production prior to 1993. The state had been shipping about 3 million head out of state for slaughter, but if the new plant is able to double-shift and run near capacity, state slaughter may also reach nearly 10 million head by 1995. These are truly enormous shifts in the market-slaughter balances of the state, and they have implications for a national redistribution of production and processing.

Contract Hog Production: The contract hog production system is well established in North Carolina. The state has a long history of using contract production in the poultry industry, so contract production in hogs was quickly accepted. The North Carolina hog production system is increasingly based upon three-site production. These three sites include the sow unit, which may be company owned or contracted; the nursery units, which are generally owned by local farmers and operated under contract; and the farmer-owned finishing units, which are also operated under contract.

Figure 2. Head of Hogs Marketed and Slaughtered In North Carolina

There are two important reasons contract production is helping to accommodate the rapid growth of the industry. The first involves the declining fortunes of tobacco. Tobacco has been the King of Agriculture in the state, literally since Europeans first settled there. Tobacco revenues allow many producers with small land bases to continue farming, but declining domestic tobacco use raises concerns for the future. Livestock contracts provide a way to stay on the farm and to enter a complex business with limited background or training. Thus, there is a waiting pool of farmers who are interested in contract nurseries or contract finishing units.

A second critical reason contract production contributes to rapid growth involves the financial leverage it provides to the owner of the hogs. Owning all of the buildings and equipment to raise hogs ties up large amounts of equity capital. How-ever, if a contractor owns only the farrowing unit and contract producers own the nurseries and finishing capacity, this reduces by about one-half the total investment in buildings and equipment for a farrow-to-finish operation. A contractor can build one farrow-to-finish unit or build two farrowing units with contract nurseries and finishing with the same equity capital investment in buildings and equipment. Thus, to grow rapidly, they choose the two farrowing units.

Scale and Systems Approach to Production: Hog producers in North Carolina think in big volumes when it comes to raising hogs. They had the first 1,000 sow farm back in 1969, and by 1974 one of the main hog producers had settled on a 1,250-sow farm size. Today, a number of large commercial farms have a mini-mum scale of 2,000 sows in their far-rowing units. State Veterinarian data shows that there are 211 farm locations with over 1,000 sows. The average number of sows on these farms is 1,536. A total of 184 farms are between 500 and 999 sows, with an average of 622 sows. These two size groups of 395 farms have 73.5 percent of all the sows in the state.

The large commercial operations have used a systems approach. This means that they have developed a standardized set of buildings, equipment, and hog management with the objective of minimizing costs. Once this system is established they can replicate it. Thus, scale and standardization allow rapid expansion.

Environmental and Regulatory Factors: Regulations are still relatively unobtrusive in North Carolina. Water quality laws prohibit dis-charge into open streams or in any way impacting the quality of water. New registration requirements will require those farms with 250 or more hogs to register with the state by the end of 1993 and to have a qualifying waste disposal plan in place by the close of 1997 (Barker, EBAE 164-93).

Citizens action groups have targeted the hog production industry as a potential violator of environmental standards. New legislation has been introduced in the state legislature to greatly restrict the North Carolina hog production system. However, to date, the industry has been able to retard these attempts and to divert these groups toward supporting research to understand the impacts of large scale hog concentration and to improve technology and management practices.

From a midwest perspective (where it can be difficult to get permits to build one new 1,000 sow unit), it is clear that North Carolina’s environmental and regulatory constraints are less restrictive to rapid expansion.

Manure Disposal Systems and Nitrogen Loading: Much of the state’s swine waste disposal system is based upon buildings with flush-under-slat design. Waste is flushed from buildings to a single stage lagoon, and effluent from the lagoon is used to irrigate crops around the buildings. The crop of choice is coastal bermuda grass, which has a voracious appetite for nitrogen—the nutrient basis for establishing loading rates (Barker, EBAE 103-90).

The warm climate provides for decomposition of about 75 percent of the nitrogen in the lagoons (Safley and Westerman). Since coastal bermuda grass uses such large amounts of nitrogen, relatively small acreage may be required for irrigation. Depending on soils and grass yield, this may be in the range of 80 acres per 1,000 sows farrow-to-finish. The bermuda grass is grazed with brood cows or stocker cattle, or alternatively is baled if a cash hay market is available. Interestingly, the cattle industry is being spurred as a by-product of the hog industry. This cattle-following-the-hogs is an interesting reversal of the old hogs-follow-the-cattle management of diversified farms of years ago.

Expansion is facilitated by the fact that it takes relatively small land bases for high concentrations of animals, and in general, there remains a relatively large amount of marginal land.

Supportive Financial Lenders: The contract production system in the state has been successful in hogs partially because the mega-farms who write many of the contracts have made sure that the banks and families involved are financially successful. We heard farmers and bankers alike say that, “We have never had a failure on a hog contract from one of the major players.” In part due to the faith in the mega-farms which write contracts, lenders are willing to make loans at competitive interest rates for contract nurseries and contract finishing buildings. This has been an important factor in supplying the needed debt capital to local farmers who are contract producers and in allowing rapid expansion.

Favorable Costs of Production: Surprisingly to most in the corn-hog belt, North Carolina producers believe they can be low-cost producers of pork. While their feed grain deficit is a disadvantage, they have some other costs advantages in sharply lower building costs, lower labor costs, lower waste disposal costs, perhaps lower interest rates, and lower transportation costs on finished pork products to east coast markets.

Summary and Conclusions

The North Carolina pork industry is in a boom of surprising magnitude. Production is expected to rise from about 4 million head in 1987 to near 10 million head by 1995. If realized, the state will likely be the second largest hog state, trailing only Iowa.

Why North Carolina, and why now? The reasons are unique to the people and circumstances which have developed there. The most important driving force is the addition of the country’s largest pork processing plant, which is working closely with producers to supply their kill. A system of contract pro-duction is in place, the regulatory environment is accepting, a system of large-scale production can be quickly replicated, and there is a pool of farmers and bankers anxious to become part of a growth industry in the region.

In summary, North Carolina is where it could — and is — happening. But the North Carolina model has not gone unnoticed, as similar production and coordinated processing systems have been initiated in such states as Arkansas, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah.

Success, however, is not guaran-teed by size or expansion. The highly coordinated North Carolina system of production and processing will face a major financial test in 1994 as increased production there, and by specialized firms elsewhere, drive pork profit margins down. If they are not successful, we midwesterners will breathe a sigh of relief, but if they are, much of the national industry can be expected to follow their lead, which could accelerate the cur-rent rate of structural change in the industry.

References

Barker, James C. “Water Quality Nondischarge Regulations for Livestock Farms In North Carolina.” EBAE 164-93. North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service, North Carolina State University, January 1993.

Barker, James C. “Lagoon Design and Management For Livestock Waste Treatment and Storage.” EBAE 103-90. North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service, North Carolina State University, January 1990.

Hogs and Pigs reports, various issues. National Agricultural Statistics Service, USDA, Washington, D.C.

Safley, L.M. and P.W. Westerman. “Performance of a Low Temperature Lagoon Digester.” Bioresourse Technology: 41(1992), pp. 176-175.

Standard OTC Stock Reports, Vol 59, No. 40, Standard and Poors Corporation, 25 Broadway, New York, New York.