2008 Indiana Farmland Value & Cash Rent Continue Sharp Upward Climb

August 1, 2008

PAER-2008-11

Craig L. Dobbins, Professor and Kim Cook, Research Associate

State‑wide Farmland Values

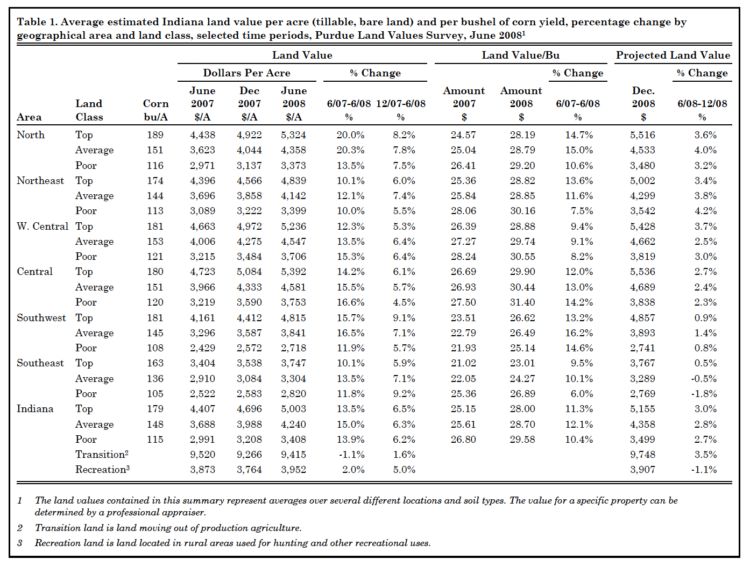

With the sharp increase in grain prices, it probably is no surprise that the 2008 Purdue Farmland Value and Cash Rent Survey found farmland value and cash rent moving higher. On a state‑wide basis, the average value of bare Indiana cropland ranged from $3,408 per acre for poor quality land to $5,003 per acre for top quality land (Table 1). Average quality Indiana cropland had an estimated average value of $4,240 per acre. For the 12‑month period ending in June 2008, this was an increase of 13.9%, 15.0%, and 13.5%, respectively for poor, average, and top quality land. These double‑digit increases are less than those reported last year, but still signal a strong farmland market. Since June 2006, Indiana farmland values have increased by about one‑third (32.7%, 34.1% & 35.8% for poor, average, and top quality farmland).

The value of farmland is influenced by many factors. One often cited reason for differences in the value of farmland is soil productivity. To assess the productivity of the various land qualities, survey respondents were asked to provide an estimate of the long‑term corn yield for poor, average, and top quality land. These estimates are averaged to provide a measure of the productivity for each land type. For the state, the average of the reported yields was 115, 148, and 179 bushels per acre, respectively for poor, average, and top quality land. State‑wide, the value per bushel of corn for different land qualities ranged from $28.00 to $29.58 per bushel. On a per bushel basis, the most expensive land is the poor quality land with a value of $29.58 per bushel. Top quality land was the least expensive at $28.00 per bushel.

The average value of transitional land, farmland moving out of agriculture, declined slightly this year. The average value of transitional land in June 2008 was $9,415 per acre. This was a decline of 1.1% when compared to the average value in 2007. Given all the news about slow growth in the general economy and difficulties in the housing industry, some softening of this market would be expected. However, the value of transitional land is strongly influenced by what the land is transitioning into and its location. In June 2008, transitional land values ranged from $2,500 to $55,000 per acre. Because of the wide variation in values of transitional land, the median value* may give a more meaningful picture than the arithmetic average.

* The median is the middle observation in data that have been arranged in ascending or descending numerical order.

Table 1. Average estimated Indiana land value per acre (tillable, bare land) and per bushel of corn yield, percentage change by geographical area and land class, selected time periods, Purdue Land Values Survey, June 20081

The median value of transitional land increased from $7,500 per acre in June 2007 to $8,000 in June 2008.

The state‑wide average value of rural recreational land, land used for hunting and other recreational uses, is $3,952 per acre. As with transitional land, there is a wide range of values for rural recreational land. The June values reported for recreational land varied from $1,100 to $15,000 per acre. The median value for rural recreational land in June 2008 was unchanged from June 2007 at $3,500 per acre.

State‑wide Rents

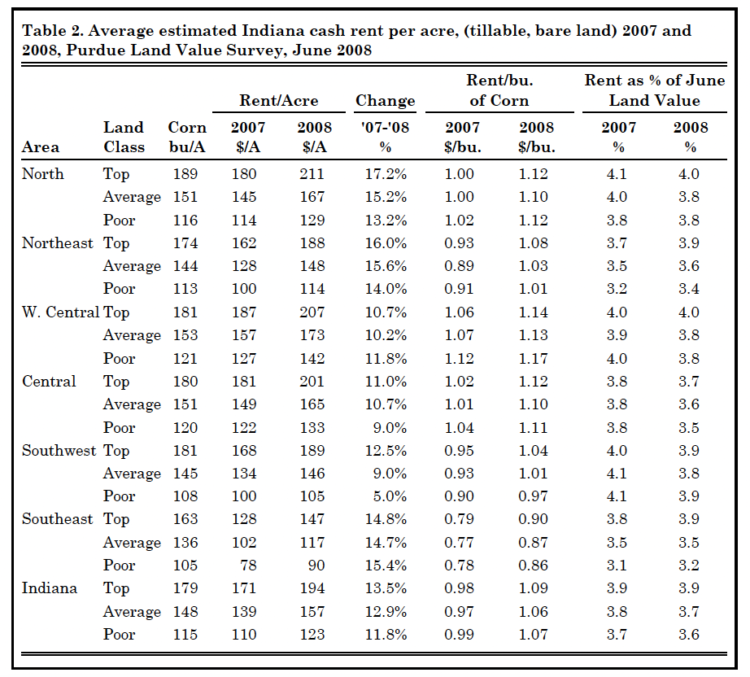

One important contributor to the value of farmland is the annual rent that can be obtained from ownership. State‑wide, cash rents increased $13 to $23 per acre (Table 2). The largest dollar increase in rent was for top quality land. The smallest dollar increase in rent was for poor quality land. The average estimated cash rent was $194 per acre on top quality land, $157 per acre on average quality land, and $123 per acre on poor quality land. This was an increase in rental rates of 11.8% for poor quality land, 12.9% for average quality land, and 13.5% for top quality land. State‑wide, rent per bushel of estimated corn yield increased to $1.06 to $1.09 per bushel.

Table 2. Average estimated Indiana cash rent per acre, (tillable, bare land) 2007 and

2008, Purdue Land Value Survey, June 2008

For top quality farmland, cash rent as a percentage of farmland value was 3.9%. For average and poor quality farmland, cash rent as a percentage of farmland value was 3.7% and 3.6%, respectively. These percentage values were either the same or only slightly less than those reported in 2007, indicating a possible pause in the downward trend in this percentage. Over the 34‑year history of the survey, rent as a percentage of farmland value has averaged about 6.0%.

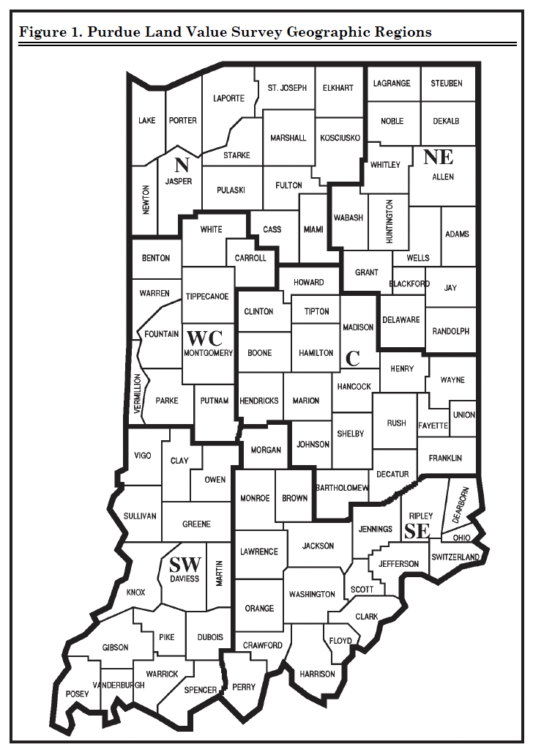

Area Land Values

Survey responses were organized into six geographic regions (Figure 1). As in the past years, there are geographic differences in land value changes. This year, the North region reported the strongest percentage increase in farmland values. Bare farmland in this area was estimated to have increased 13.5% to 20.3% (Table 1). The increase in value for the West Central, Central, and Southwest region was also strong with increases ranging from 11.9% to 16.6%. The increases in value for the Northeast and Southeast were more modest, ranging from 10% to 13.5%.

The highest value per acre for top, average, and poor quality farmland is in Central Indiana. However, the dollar value of top, average and poor quality farmland is very similar in the Central, West Central and North regions. The lowest farmland values continue to be in the Southeast.

Land value per bushel of estimated long‑term corn yield (land value divided by bushels) is the highest in the North, Central and West Central regions, ranging from $28.19 to $31.40 per bushel. This is followed by the Northeast and Southwest, ranging from $25.14 to $30.16 per bushel. The Southeast had the lowest land values per bushel, ranging from $23.01 to $26.89 per bushel. The most expensive farmland per bushel of corn yield in all regions except the Southwest was poor quality land.

Figure 1. Purdue Land Value Survey Geographic Regions

Area Cash Rents

There were strong increases in cash rents in all areas of the state. The strongest percentage increases were in the North, Northeast and Southeast, with increases between 13.2% and 17.2% (Table 2). There were only three percentage increases in cash rent that were not in double digits. These were for poor quality land in central Indiana at 9.0%, and average and poor quality land in Southwest Indiana at 9.0% and 5.0%, respectively.

For the first time, cash rents for top quality land in the North, West Central, and Central regions have all broken the $200 per acre mark. Another first is the highest cash

rent has shifted from the West Central region to the North region. The highest cash rents are found in the North, West Central, and Central regions of the state. This is followed by cash rents in the Northeast and the Southwest. Cash rents are the lowest in the Southeast.

Differences in productivity have a strong influence on per acre rents. To adjust for productivity differences, cash rent per acre was divided by the estimated corn yield. Rent per bushel of corn yield for the North, West Central, and Central regions are similar, ranging from $1.10 to $1.17 per bushel. In the Northeast and Southwest regions, cash rent per bushel ranged from $0.97 to $1.08. Per bushel cash rent in the Southeast ranged from $0.86 to $0.90 per bushel.

Dispersion of Responses

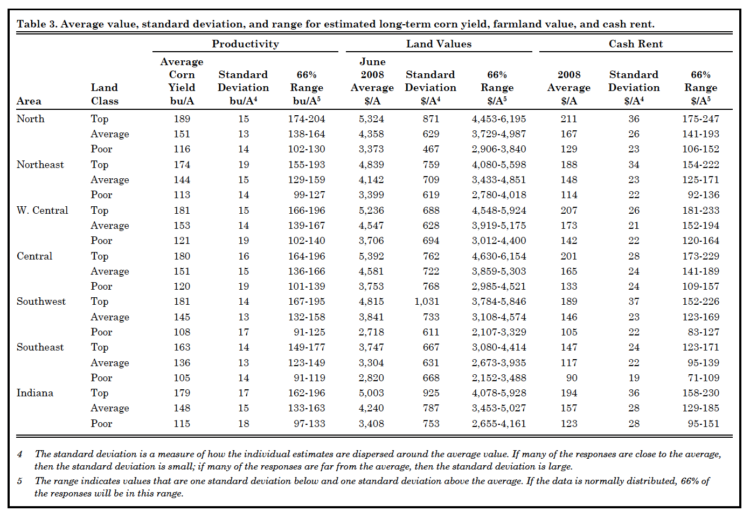

The data contained in Tables 1 and 2 provides information about the average of the responses received in the survey. Another important aspect of these responses is the dispersion of the responses around the average. One measure of dispersion is the standard deviation. Why is the dispersion of the responses important? It is possible to have the same average but have a difference in the range of data or dispersion. From a statistical perspective, there is more confidence in an average of a data sample if the dispersion around the sample average is small.

Information about the dispersion of responses for corn yields, June farmland values, and cash rent is provided in Table 3.

To illustrate the use of this information, note that the June value of top quality land in the Northeast and the Southwest is similar, $4,839 in the Northeast and $4,815 in the Southwest. The standard deviation for the average is $759 in the Northeast and $1,031 in the Southwest. The larger standard deviation indicates that while the average is about the same the range of

estimates was larger in the Southwest. The greater dispersion is also indicated by the range. The range in Table 3 indicates the value that is one standard deviation above and below the average. If it is assumed that the data is normally distributed, then 66% of the values would fall in this range. Assuming that estimates are normally distributed, 66% of the responses providing the Northeast average of $4,839 would be between $4,080 and $5,598. For the Southwest, 66% of the responses providing the average of $4,815 would be from a wider range of $3,784 to $5,846.

Table 3. Average value, standard deviation, and range for estimated long-term corn yield, farmland value, and cash rent.

Rural Home Sites

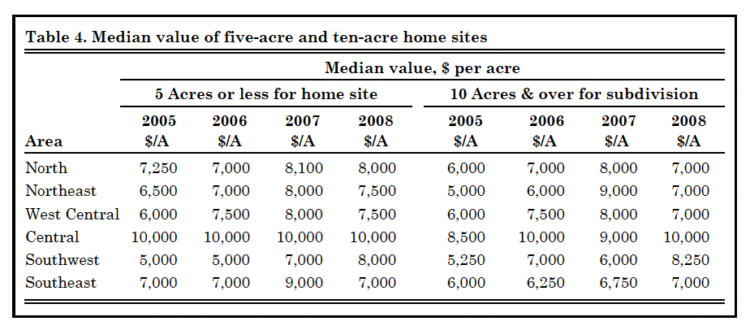

Respondents were asked to estimate the value of rural home sites with no accessible gas line or city utilities and located on a black top or well‑maintained gravel road. The median value for five‑acre home sites ranged from $7,000 to $10,000 per acre (Table 4). The median values in the North, Northeast, West Central, and Southeast regions declined. Estimated per acre median values of the larger tracts (10 acres) ranged from $7,000 to $10,000 per acre. The median values in the North, Northeast, and West Central regions declined. The decline in these values indicate that at least in some areas of the state the demand for rural home sites is not as strong as it once was and probably reflects the weaker residential housing market in general.

Table 4. Median value of five-acre and ten-acre home sites.

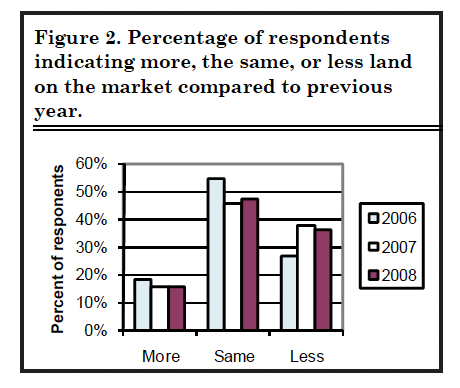

Figure 2. Percentage of respondents indicating more, the same, or less land on the market compared to previous year.

Farmland Supply & Demand

To assess the supply of land on the market, respondents were asked to provide their opinion of the amount of farmland on the market now compared to a year earlier. The respondents indicated either more, the same, or less land was on the market than one year ago. Only 16% of the 2008 respondents indicated more land was on the market now compared to year‑ago levels (Figure 2). The remaining 84% of the respondents indicated the amount of land on the market at the current time was the same or less than a year ago. Compared to 2006 and 2007, there has been little change in the number of respondents indicating more land was on the market. For 2007 and 2008 several respondents shifted from indicating the same amount of land was on the market to indicating there was less.

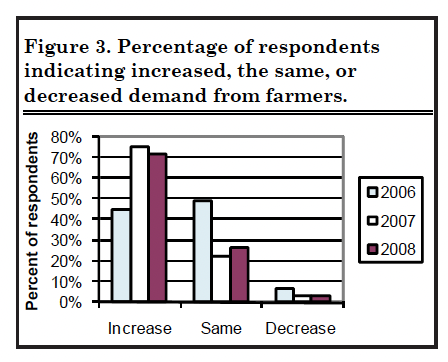

Respondents were also asked to provide their perception of changes in demand for farmland. One source of farmland demand is farmers seeking to expand the size of their businesses. Respondents were asked to indicate if the demand from farmers had increased, remained the same, or decreased when compared to a year earlier. The number of respondents indicating an increased demand from farmers increased significantly in 2007 and was nearly as high in this year’s survey (Figure 3). This year, 71.4% of the respondents indicated increased farmer demand. Only 2.6% indicated a decrease in demand from farmers. The remaining 26% of the respondents indicated that farmer demand remained the same.

Figure 3. Percentage of respondents indicating increased, the same, or decreased demand from farmers.

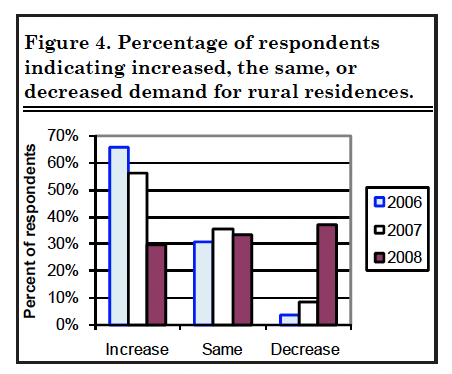

Figure 4. Percentage of respondents indicating increased, the same, or decreased demand from farmers.

Rural home sites are another use of farmland. This has been a strong source of demand for the past several years. Over the last year there has been a lot of discussion of the difficulties in the housing market. These difficulties appear to be influencing the demand for rural residences. This year, less than 30% of the respondents indicated that there was increased demand for rural residences (Figure 4). The number of respondents indicating a decrease in demand for rural residences was 37%. The remaining 33% of the respondents indicated no change.

Nonfarm investors are another group that contributes to the demand for farmland. Respondents were asked to indicate if they perceived an increase, the same, or a decrease in demand from individual investors as well as organized investment efforts such as pension

funds. This year there were more respondents indicating a decrease in demand from these two sources. However, the changes were modest.

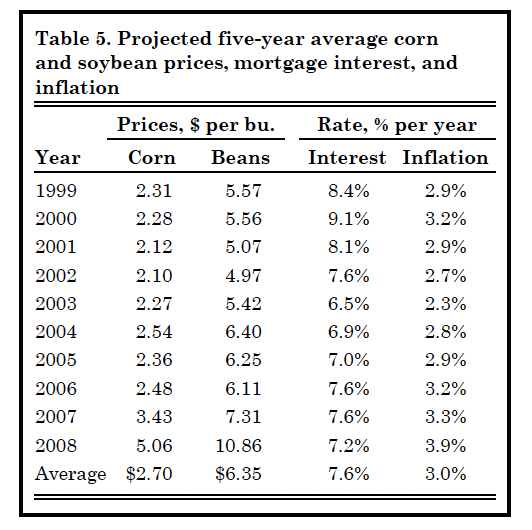

Expected Grain Prices, Interest Rates, & Inflation

Making a farmland purchase is a long term commitment. As a result, expectations regarding crop prices over the next few years can have a strong influence on farmland values. Given the record high prices for corn and soybeans, it is likely that these expectations have sharply changed. In order to gain insight into crop price expectations, respondents were asked to estimate the annual average on‑farm price of corn and soybeans for the period 2008 to 2012. This year saw another large increase in the expected five‑year average price of corn and soybeans. On average, survey participants expect corn prices to be $5.06 per bushel and soybean prices to be $10.86 per bushel, estimates that are well above the 10‑year average (Table 5).

Mortgage interest rates have important implications for real estate markets. While mortgage interest rates have increased from their lows of a few years ago, they continue to be modest.

Table 5. Projected five-year average corn and soybean prices, mortgage interest, and inflation

Figure 5. Influence of selected factors on Indiana farmland values.

Survey respondents don’t seem to be expecting much change in mortgage interest rates. The average estimate of 7.2% in 2008 is below the 10‑year average of 7.6%.

Inflation rate expectations continue to increase. On average, survey respondents estimate annual inflation over the next five years will be 3.9%. This is almost 1% above the average for the 10‑year period and is the highest expected inflation rate for the 1999 to 2008 period.

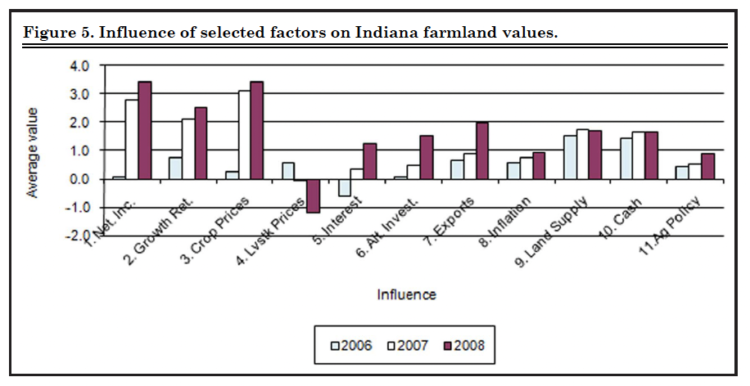

Market Influences

To obtain a more complete picture of the strength that various influences exert on farmland values, survey respondents were asked to assess the influence of 11 different items on farmland values. These items included:

- Current net farm income

- Expected growth in returns to land

- Crop price level and outlook

- Livestock price level and outlook

- Current & expected interest rates

- Returns on competing investments

- Outlook for U.S. agricultural export sales

- U.S. inflation/deflation rate

- Current inventory of land for sale

- Current cash liquidity of buyers

- Current U.S. agricultural policy

Respondents were asked to use a scale from ‑5 to +5 to indicate the effect of each item on farmland values. A negative influence would be given a value from ‑1 to ‑5, with a ‑5 representing the strongest negative influence. A positive influence was indicated by assigning a value between 1 and 5 to the item, with 5 representing the strongest. An average for each item was calculated.

In order to provide a perspective on the changes in these influences, data from 2006, 2007 and 2008 are presented in Figure 5. The horizontal axis of the chart indicates the item in the list above. For this three year period, most of the items have a positive influence. In 2006, the current and expected interest rate had a negative influence. In 2007, the livestock price level and outlook over the last three years. The only negative influence for the farmland market in 2008 is livestock price level and outlook.

Expected Future Land Values

The increase in crop prices has led to several other changes. As an industry, markets are sorting through how the increased margin from crop production will be shared among market participants. Expectations about corn and soybean prices, interest rates, and the other influences impacting the land market indicate that there will be future increases in farmland values. Increased farmland values are also reflected in the projected land values for December 2008 and the five year estimates provided by survey respondents.

On a state‑wide basis, Table 1 indicates that for the six‑month period from June to December 2008, survey respondents expect farmland values to increase 2.7% to 3.0%. Generally survey respondents in the North, Northeast, and West Central regions expect increases larger than the state‑wide average. Respondents in the Central, Southwest, and Southeast regions are expecting increases smaller than the state average. Respondents in the Southeast expect to see a slight decline in land values for average and poor quality farmland. If these expectations are used to project an annual increase in land values, they indicate a much lower rate of increase than has occurred during the past two years.

Respondents were also asked to project farmland values five years from now. Seventy‑two percent of the respondents expect farmland values to be higher, 16% percent expect farmland values to be the same as in 2008, and 12% expect farmland values to be lower. For those expecting land values to increase, the average expected increase for the five year period was 14%. This would translate into an average annual increase of 2.66%. For those expecting land values to decline over the next five years, the average decline was also 14%. Combining all responses provided an expected total increase in farmland value for the next five years of 8.6%. These projections indicate that survey respondents expect the increase in farmland values to slow significantly.

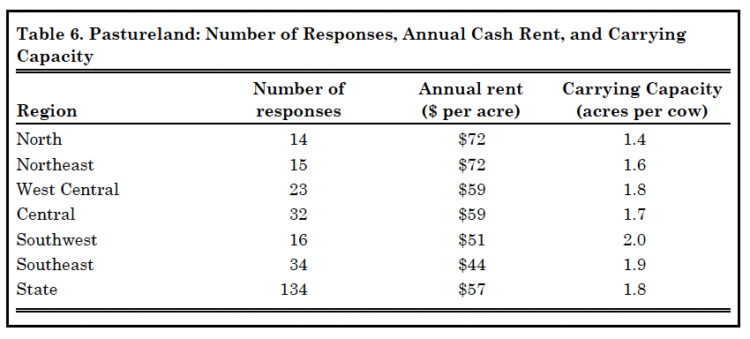

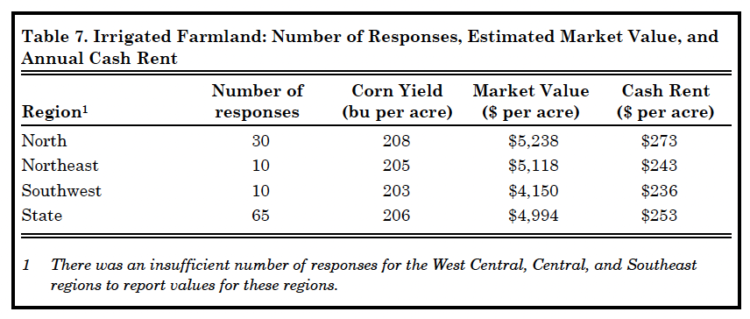

Pasture Rent, Irrigated Farmland, & Grain Storage Rent

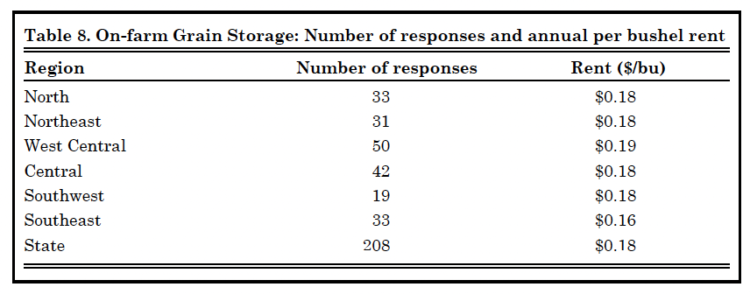

The information on pasture rent, rental of irrigated farm land, and rental of on-farm grain storage was updated in this survey. The 2008 averages for pasture rent, the value and cash rent of irrigated farmland, and the rental of on-farm grain storage are presented in Tables 6, 7 and 8, respectively.

Table 6. Pastureland: Number of Responses, Annual Cash Rent, and Carrying Capacity

Table 7. Irrigated Farmland: Number of Responses, Estimated Market Value, and Annual Cash Rent

Table 8. On-farm Grain Storage: Number of responses and annual per bushel rent

Final Comment

The 2008 Purdue Farmland Value and Cash Rent Survey indicates both Indiana farmland values and cash rents made a significant increase over the past year. There is a limited supply of land for sale or rent. There is a bright outlook regarding grain prices. The liquidity of buyers appears strong. If borrowed funds are needed, favorable interest rates are anticipated by survey respondents. In addition, most respondents expect farmland values to continue to increase.

While there are several positive factors contributing to a strong demand for land from farmers and investors. There are a few items that could create some unease in the farmland market.

- Increasing production costs. Fuel prices have increased substantially since last year and seem to continue to rise. Input suppliers are signaling that there will be substantial increases in seed, fertilizer, and chemical prices associated with the 2009 crop. These rising input prices are eroding the increased margin provided by higher grain prices.

- A decline in crop prices. We have seen how quickly prices can rise. It is important to remember that they can also decline rapidly. While futures prices indicate grain prices are likely to remain strong for the next few years, it is important to recognize that prices do not need to return to their pre‑boom level to create a cost‑price squeeze. Higher input prices and higher cash rent have significantly increased the cost of crop production. The government program that depends on target prices of $2.63 per bushel for corn and $5.80 per bushel for soybeans no longer provides enough revenue to cover purchased inputs and cash rent.

- Tight supplies of corn and soybeans will continue to mean more volatile commodity prices and thus volatile margins. The use of fixed cash rent leases has shielded the nonfarming farmland owner from the income variability associated with a farmland investment, but there is an effort on the part of some landowners and tenants to shift to flexible cash rent. It is unclear how the increased margin variability and change to a flexible cash rent lease may cause land market participants to adjust their risk premiums.

These items are not likely to stop farmland values and cash rents from continuing their strong march upward in the year ahead. If you participate in the farmland market in this new environment, it may be helpful to prepare a list of what could go right and what could go wrong, estimate the consequences associated with each outcome, ask yourself the likelihood of each outcome occurring, and evaluate the financial impacts.

Purdue Land Value and Cash Rent Survey

The Purdue Land Value and Cash Rent Survey is conducted each June. The survey was made possible through the cooperation of numerous professionals that are knowledgeable of Indiana’s farmland market. These professionals include farm managers, appraisers, land brokers, agricultural loan officers, Purdue Extension educators, farmers, and persons representing the Farm Credit System, the Farm Service Agency (FSA) county offices, and insurance companies. Their daily work requires that they stay well informed about land values and cash rents in Indiana.

These professionals are asked to provide an estimate of the market value for bare poor, average, and top quality farmland in December 2007, June 2008, and the expected value for December 2008. They are also asked to provide an estimate of the current cash rent for each land quality. To assess the productivity of the land, respondents provide an estimate of long-term corn yields. Respondents are also asked to provide a market value estimate for land transitioning out of agriculture.

Responses from 327 professionals are contained in this year’s survey representing all but one Indiana county. There were 47 responses from the North region, 54 responses from the Northeast region, 77 responses from the W. Central region, 76 responses from the Central region, 36 responses from the Southwest region, and 37 responses from the Southeast region. Figure 1 illustrates the counties in each region.

Appraisers accounted for 18% of the responses, farm loan professionals represented 62% of the responses, farm managers or farm operators provided 11% of the responses, and other professionals provided 9% of the responses.

The data reported here provide general guidelines regarding farmland values and cash rent. To obtain a more precise value for an individual tract, contact a professional in your area that has a good understanding of the local situation.

We express appreciation to Marsha Slopsema of the Department of Agricultural Economics for her help in conducting the survey.