Indiana’s 2008 Property Tax Reforms Part 2

August 18, 2008

PAER-2008-13

Larry DeBoer, Professor

During the 2008 short session the General Assembly passed and the Governor signed the most sweeping reform of property taxes and local government finance in at least 35 years. This article is part 2 (part 1 appeared in the May PAER) of a description of these reforms, as well as a look at some of the potential consequences.

The new “circuit breaker” is a simple idea with complicated consequences. It limits tax bills to a fixed percentage of assessed value before deductions. By 2010, if a house is assessed at $120,000, its tax bill cannot exceed $1,200—a 1% circuit breaker limit. Other residential property and farmland have a 2% limit, and all other property has a 3% limit. The state will not pay for these credits, so what taxpayers don’t pay, local governments don’t receive. Circuit breakers also imply that local budgets are interdependent. When one government changes its tax rate, the revenues of other governments are affected.

The circuit breaker interacts with other new features of HEA1001. Bigger capital projects will now be subject to voter referendums. With circuit breakers, the referendum decisions of one government could affect revenues of other governments. Most property assessments now will be done by counties, not townships. The circuit breakers mean that all governments have an interest in assessing quality.

Homeowner property taxes will fall. The sales tax rate has already increased. Will households pay more or less overall? And, since taxes paid by landlords and businesses will change too, will these taxes be passed along to tenants and customers? The last section of this article addresses these questions.

Property tax stability.

The circuit breakers have consequences which will be new to Indiana local governments (and taxpayers). The property tax has been the most stable revenue source for local governments. This was partly due to the ability of local governments to adjust the tax rate to deliver a particular tax levy, whatever happened to assessed value. If assessed value dropped (or grew more slowly) due to recession, tax rates could increase to compensate. Revenues would continue to grow.

With the circuit breakers, property tax revenues may be more vulnerable to recession. Suppose that property values decline during a recession. Trending will reflect this in lower assessed values after a couple of years. Tax rates could rise to compensate. But lower assessed values mean lower circuit breaker tax bill limits. With the compensating tax rate increases, more property owners would be eligible for more circuit breaker credits. Local governments would lose more revenue from the circuit breakers. A decline in assessed value will produce a decline in property tax revenue in jurisdictions with significant circuit breaker credits. Local governments may have to cut their budgets in years following recessions, because property tax revenues will respond to recessions.

From the taxpayer’s point of view, this is an advantage, not a problem. The property tax achieved stability by ignoring fluctuations in property values. If property values fell, the rate would rise, regardless of the recession’s effect on the taxpayer’s ability to pay. Now, the circuit breaker will put an upper limit on the tax bill, and that limit will tighten if property values fall.

Local income taxes.

In 2007 the General Assembly created three new local income taxes. HEA 1001 left these taxes mostly unchanged. One of the taxes allows a freeze of the property tax levy for non‑school operating funds. The annual increases in these revenues are funded by an income tax rate. The upper limit on this tax is one percent. A second tax can be adopted to replace existing property taxes. The relief can be distributed as property tax credits to all property owners, just to homeowners, or just to homeowners and rental housing owners. The maximum income tax rate is one percent. A third local income tax can be used to add revenues for public safety, at a rate up to 0.25%. One of the other taxes must be adopted before the public safety tax can be adopted. (This is a change. Before, both had to be adopted.) Fourteen counties adopted versions of these taxes in 2007, effective for 2008.

These income taxes cannot be used to directly fund circuit breaker revenue losses. However, adopting these taxes can reduce losses from circuit breakers. Consider again the $120,000 homeowner at the $3 rate, with a circuit breaker credit of $173. Suppose the county adopts a local income tax, and decides to provide a property tax credit to all taxpayers. This might work out to a 20% credit. Taxpayers would see a 20% credit on their tax bills. The new local income tax would replace the lost property tax revenue from this credit for local governments.

This 20% credit would reduce the pre‑circuit breaker tax bill of the homeowner by $275, from $1,373 to $1,098. The new tax bill is less than the $1,200 circuit breaker limit, so the homeowner would not receive the circuit breaker credit. The homeowner’s post‑circuit breaker tax bill drops from $1,200 to $1,098, which is $102. The local governments gain $275 in new income tax revenue, but lose only $102 in property tax revenue. The net of $173 is new revenue for local governments.

There may be a strategic decision here for local governments. The three methods of distributing tax relief—to all property owners, to homeowners only, or to homeowners and rental housing owners only—will produce different combinations of tax relief and revenue gains. For example, suppose most of the local governments’ circuit breaker losses are from credits to rental housing owners. Distributing tax relief to homeowners and rental housing owners will reduce rental housing property tax bills the most, and so eliminate more circuit breaker losses. This may be why HEA1001 requires local officials to hold a hearing to explain why a particular income tax relief distribution is chosen, if it’s not given entirely to homeowners.

Will the circuit breaker limits cause more counties to adopt local income taxes? If so, Indiana’s tax base will shift even further away from property taxes. Widespread adoption would also change the calculation of tax changes for households. Households in adopting counties would pay higher income taxes. Those households without circuit breaker credits could see larger additional property tax reductions, and could pay less overall. Those households who have circuit breaker credits would see smaller additional property tax reductions, and could pay more overall. The effect on taxpayers depends as well on how the tax relief is distributed. If relief goes to all taxpayers, most homeowners would see higher taxes overall. If it goes just to homeowners, most would see lower taxes overall.

Capital Projects Referenda.

Most states use referenda for capital projects; until now, Indiana has not. In most states, local governments must put their large capital projects to a vote of their citizens. If the voters approve, the money is borrowed, the project is built, and the taxpayers commit to repay the principle and interest. If the voters do not approve, the project does not move forward.

HEA1001 creates a new referendum process for Indiana to partially replace the state’s unique petition‑remonstrance process. Larger projects will be eligible for referenda: high schools costing more than $20 million, elementary schools, middle schools and junior high schools costing more than $10 million, and all other school or non‑school projects costing more than $12 million. In smaller jurisdictions lower thresholds may apply. These larger projects are subject to referenda if 100 or more voters or property owners sign a petition requesting one. Smaller projects are still subject to the petition‑remonstrance process.

Projects passed by referenda are not subject to the circuit breaker limits. The added debt service tax rate will be fully paid by all taxpayers. This exemption was created because voters whose property is already taxed at the circuit breaker maximum would not have to pay extra taxes if a project was subject to the circuit breakers. The project would be free to these voters, who would likely vote in favor. Taxpayers under their circuit breaker limits would pay the whole added tax. The referendum process could promote more capital spending in such jurisdictions. With capital projects outside the circuit breaker limits, voter approval implies a willingness to pay for the project. Smaller projects subject to petition‑remonstrance are inside the circuit breaker limits.

It seems likely that the referendum process will reduce the number of capital projects built by Indiana local governments. During the past twelve years there have been only 94 remonstrance challenges to capital projects. In about half the opponents won; in half the proponents won. We have no count, but there must have been hundreds of capital projects that moved forward without a remonstrance challenge. In Illinois, where most capital projects are subject to referenda, about 65% of 730 bond referenda passed during this period. Since so few projects are challenged by remonstrance, the approval rate for projects is likely much greater in Indiana than it is in Illinois. If Indiana voters are like those in Illinois, the referendum process will produce more rejected projects.

This creates a choice for those who favor and those who oppose capital projects. A smaller project is more certain to move forward, under the petition‑remonstrance process. It may not provide all the benefits that proponents want, but it raises the tax rate less. It is subject to the circuit breaker limits, so it could reduce revenues to other funds, and for overlapping governments. A larger project is less certain to pass, under the referendum process. It may provide more benefits, while raising the tax rate more. It is not subject to the circuit breaker limits, so it will not reduce other revenues. Which will proponents and opponents prefer? Take the more certain lower spending, lower tax project? Or risk the project with higher spending and higher taxes if it passes, and no added spending or taxes if it is defeated?

Assessment Reform.

Most states base their assessment administration with counties. Until now, Indiana has based assessment administration with townships and counties. HEA1001 transfers the assessing duties of the township‑trustees to the county assessor. It eliminates the office of elected township assessors in townships with fewer than 15,000 real property parcels, and transfers their duties to the county assessor. Elected township assessors in bigger townships will face a referendum in November 2008 to decide whether their positions will continue. In addition, certification requirements for assessors and their staffs will increase.

Studies have found that assessment quality is improved by full‑time assessors using modern assessment tools. Most Indiana townships are too small to occupy a full‑time assessor, so most township‑trustee assessors are part‑time. Moving assessment duties to the counties will put that function in the hands of a full time assessor, so consolidating to counties may promote quality indirectly. Research has not found strong evidence that county‑level assessment itself promotes quality, however. Most elected township assessors are full‑time, because only larger townships qualify for such a post. Consolidation to counties may not improve assessment quality in those townships.

There is evidence of economies of scale in assessing. Larger units can assess property more cheaply per parcel than smaller units. However, it seems unlikely that Indiana’s consolidation to counties will result in much cost savings. Trustee‑assessors are part‑time officials who receive little pay. County assessors will have to hire additional certified staff in order to take on their duties. Consolidation may improve quality, but it is unlikely to save much money.

The circuit breakers may interact with assessment practice to improve quality in a different way. Without the circuit breakers, under-assessment of property could be made up with higher tax rates. With the circuit breakers, the combination of lower assessed values and higher tax rates is likely to increase circuit breaker credits. Underassessment costs local governments revenue, so local officials have a reason to oppose underassessment. Taxpayers, as always, oppose over-assessment. The squeeze from above and below may encourage greater assessment accuracy.

Household tax changes.

Property taxes will fall. Sales taxes have increased. Will taxpayers pay more or less overall?

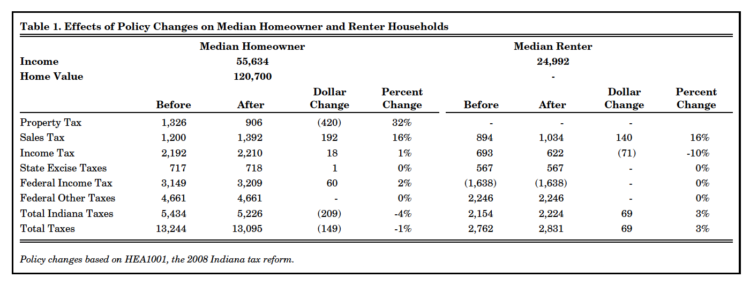

Table 1 runs the numbers for the median Indiana homeowner and the median Indiana renter. The medians come from the U.S. Bureau of Census’ American Community Survey. Data are for 2006. The median home in Indiana is valued at $120,700, and the median household income of a homeowner is $55,634. The median household income for a renter is $24,992. Each household is assumed to have three people, two adults and one child. Spending on sales taxable products was estimated by income and household size using the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey.

Taxes are calculated based on Indiana’s current system and on the changes when the new system is fully phased in as of 2010. The state average property tax reduction for a homeowner who is not eligible for the circuit breaker is 32%, as shown in Table 1. That’s a property tax reduction of $420 at the state average rate. This amount reflects the decline in the tax rate due to the state takeover of property tax funds, the increase in the homestead deduction, and the elimination of property tax credits.

Table 1. Effects of Policy Changes on Median Homeowner and Renter Households

The homeowner pays an added $192 in sales taxes, a 16% increase due to the one point rise in the sales tax from 6% to 7%. The median homeowner household itemizes its income taxes, so Federal, state and county income taxes increase. The lower property tax bill means a smaller property tax deduction, a higher taxable income, and so higher income tax payments. Excise taxes rise slightly. With a higher after‑tax income the household spends more on tobacco, alcohol and gasoline, which are subject to excise taxes.

The household’s circuit breaker limit is 1% of $120,700, which is $1,207. The homeowner pays $906 in property taxes. The median homeowner at state average tax rates does not qualify for a circuit breaker credit.

Overall, the homeowner household saves $209 in Indiana taxes, and $149 in total taxes. For the median homeowner, the property tax reduction exceeds the increases in sales and income taxes.

The median renter household, of course, receives no direct property tax cut. The household pays $140 more in sales taxes, because of the sales tax rate increase. State income taxes decrease by $71, $22 because of the $500 increase in the cap on the renter’s deduction, and $49 because of the increase in the Indiana earned income credit from 6% to 9% of the Federal credit.

Overall, the renter pays $69 more in Indiana taxes and total taxes. For the median renter, sales tax increases exceed state and local income tax cuts.

Economic Incidence.

Taxes on businesses may be paid by business owners, reducing profits. Or, they may be passed forward to customers in higher prices, backwards to employees in lower wages and benefits, or backwards to other input suppliers in lower land, material or machinery prices. The above analysis of the effect of HEA1001 on households is “statutory incidence,” meaning the effect on tax payments by those who receive the tax bills. If business taxes change wages and prices, however, the “economic incidence” may show different household tax changes.

Owners of rental property are expected to see significant property tax reductions due to the circuit breakers (see part 1 of this article). This will make owning rental property in Indiana more profitable, and these added profits may attract new investors to rental housing. New apartments would be built, and owners would likely reduce rents to attract tenants to their new buildings. The increase in the supply of rental housing would reduce rents below what they would have been without the property tax cuts. In this way part of the property tax reduction for landlords would ultimately reduce rents for tenants.

Research on this topic shows that property taxes do influence rents. Evidence varies, of course, but one careful study by Carroll and Yinger found that each one dollar change in landlord property taxes changes rents by 15 cents. The Indiana Legislative Services Agency estimates that property taxes on rental housing will decline $173 million by 2010. If 15% of this cut is passed on in lower rents, rents will fall by $26 million. The gross rent paid by all Indiana renters is about $5.1 billion per year, according to the American Community Survey. The property tax cut would reduce rents by about 0.5%.

The median renter in Table 1 pays $6,615 per year in rent. The property tax cut would reduce this rent by 0.5%, or $33 a year. This would cut the renter’s tax increase by almost half, from $69 to $36.

Part of the sales tax is a tax on business. Between 20% and 40% of Indiana’s sales tax is paid on business‑to‑business sales. These sales are made in the course of producing the products that businesses provide. The added sales tax makes these products less profitable, and that may cause businesses to produce less. If so, the decrease in the supply of products will raise prices for consumers. The business‑to‑business sales taxes may be passed on in higher prices to households.

How much added sales tax might Indiana consumers pay in these higher prices? Suppose that all of the tax is passed forward to consumers. Poterba finds this to be true for retail sales taxes. Suppose that by the time the taxes reach consumers in price increases, they are spread across all the products that consumers buy, so that the added tax is proportional to consumer spending. Suppose that 30% of Indiana sales taxes are on business‑to‑business sales, which splits the high and low estimates. And, suppose that half of all of business‑to‑business sales taxes are passed on to Indiana consumers. The rest would be exported to consumers elsewhere.

Indiana consumers spent about $170 billion on goods and services in 2006, estimated from the Gross Domestic Product accounts. The 6% sales tax raised $5.3 billion in that year. Thirty percent of this figure is $1.6 billion. That’s the estimate of business‑to‑business sales taxes. A one percent increase in this tax would generate about $270 million in added business‑to‑business tax revenue. If half this amount was passed on in higher prices to Indiana consumers, proportional to household spending, consumers would have paid about 0.08% of spending in extra sales taxes.

The median homeowner household spends $48,700. An added 0.08% is $39. The median renter

household spends $32,444. (This is more than the renter household’s income, implying that it is drawing upon savings or going into debt.) An added 0.08% is $26. For the homeowner, the added business‑to‑business sales tax is not enough to erase the overall tax reduction. For the renter, the added sales tax adds to the tax hike.

There’s a good deal of uncertainty in these estimates. If the business share of sales taxes is smaller, if businesses do not pass all of the sales tax to customers, or if we assume that Indiana businesses sell more to customers outside Indiana, the added tax figures will be smaller. If the business share of sales taxes is larger, if sales to consumers outside Indiana are less, or if we use the smaller estimate of Indiana consumer sales implied by the Consumer Expenditure Survey, the added tax figures will be larger.

Still, allowing for economic incidence does not appear to change the statutory incidence results: the median homeowner pays less as a result of HEA1001, and the median renter pays more.

Conclusion.

Indiana has passed a major property tax reform, HEA1001. Some of its provisions have already taken effect, such as the increase in the sale tax rate. Other provisions will take effect later this year, such as the new referendum requirement for capital projects. The state levy takeovers will be effective in 2009, and the full circuit breaker limits will take effect in 2010. Some of the

assessor certification requirements won’t kick in until the early part of next decade.

That means we will come to appreciate the full effects of HEA1001 only gradually. New, unexpected benefits and costs will arise. It may take many years to fully understand what we’ve done.

Sources

Bowman, John H. and John Mikesell. 1990. “Assessment Uniformity: The Standard and Its Attainment.” Property Tax Journal 9 (December): 219‑233.

Carroll, R.J. and Yinger, J. 1994. “Is the Property Tax a Benefit Tax? The Case of Rental Housing,” National Tax Journal 47 (June): 295–316.

DeBoer, Larry. 2007. “The Shares of Indiana Taxes Paid by Businesses and Individuals: An Update for 2006.” [www.agecon.purdue.edu/crd/Localgov/Topics/Materials/BsnsTaxShares_2006_1007.pdf]

DeBoer, Larry. 2008. “Property Tax Questions Answered by an Indiana Household Model.” (Expanded paper) Indiana Business Review website (February): 1‑13. [www.ibrc.indiana.edu/ibr/2008/spring/property‑tax‑policy‑questions‑answered.pdf]

Derrick, Frederick W. and Charles E. Scott. 1993. “Businesses and the Incidence of the Sales and Use Taxes.” Public Finance Quarterly 21 (April): 210‑226.

Indiana Legislative Services Agency. 2008. “Estimated Impact on Net Property Tax, HB1001 CC08 Update” (March 13).

Poterba, James M. 1996. “Retail Price Reactions to Changes in State and Local Sales Taxes.” National Tax Journal 49 (June): 165‑176.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statististics. 2008. Consumer Expenditure Survey. [http://stats.bls.gov/cex/home.htm]

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 2007. Quick Guide to the 2006 American Community Survey Products in American FactFinder. [http://factfinder.census.gov/home/saff/aff_acs2006_quickguide.pdf]

Walker, Mary Beth and David L. Sjoquist. 1999. “Economies of Scale in Property Assessment.” National Tax Journal 52 (June): 207‑220.

For more information, see the Indiana Local Government Information website, www.agecon.purdue.edu/crd/Localgov .