Key Factors Influencing Opportunities for Indiana Agriculture: The Long View

July 18, 2008

PAER-2008-4

Sally Thompson, Professor and Department Head; Allan Gray, Professor and Mike Boehlje, Distinguished Professor

The broad sweeping changes taking place in the global agricultural marketplace will clearly affect the potential opportunities for growth of the Indiana agricultural sector. Here, we identify five major factors that we believe will be key contributors to the shape of the future

of agriculture:

- The Intersection of Agriculture, Food, and Energy Policy

- The Global and Local Influence of Demand and Supply for Agricultural Products

- The Resurgence of Risk in Agriculture

- The Increasing Strain on Natural Resources

- The Role of Biotechnology in Redefining Agriculture

The Intersection of Agriculture, Food, and Energy Policy

While national policy has always been an important factor for agriculture, recent policy decisions regarding energy, agriculture, and food at the national level have had a profound impact on the agricultural industry. Because much of today’s volatile shift in agricultural markets is due to policy influence, we must recognize the influence that further policy decisions will have on the agricultural industry in Indiana and elsewhere.

Current energy policy, described in more detail in “Energy and Bio-fuels,” has been a major influence in the unprecedented rise in commodity prices particularly for corn, soybeans, and wheat. The Renewable Fuel Standard calling for 36 billion gallons of renewable fuels by 2022 suggests increased energy-based crop demand. This would suggest continued strong demand for corn, in the near term, and for cropland in general for some time to come. This may be good news for crop farmers for the future.

However, the pressure placed on supplies of feed grains to meet the growing biofuels demand, the export demand, and livestock demand is creating stress. Livestock producers, particularly pork and poultry, are under severe pressure, with feed costs increasing dramatically. We could see more consolidation in this industry in the near future. The issue at hand is not whether livestock can compete in the marketplace for feed grains, but rather that the current market conditions are not market driven, but policy driven. That is, national energy policy has resulted in the large increase in feed costs. Perhaps, over time, the price of poultry and pork products will rise, as consolidation reduces supplies, allowing the remaining producers to prosper. Of course, the rise in poultry and pork prices, along with other animal proteins, to offset the rising cost of feed will affect consumer prices for food.

Thus, this intersection of energy, agriculture, and food policy leads to several questions. Will Congress face increasing pressure from livestock producers and consumers in the future to change its course on energy policy? Will there be increasing pressure on agricultural policy to change course from assisting commodity crop producers, to more assistance for livestock producers? As the cost of food continues to rise, will there be increased pressure to focus agricultural/food policy more on food stamps and other assistance programs to offset this rising cost in lieu of commodity subsidies, crop insurance subsidies, and research in agriculture? Finally, what will be the impacts of second-generation biofuel technologies on resources other than corn, such as grasses or woods?

The Global and Local Influence of Demand and Supply for Agricultural Products

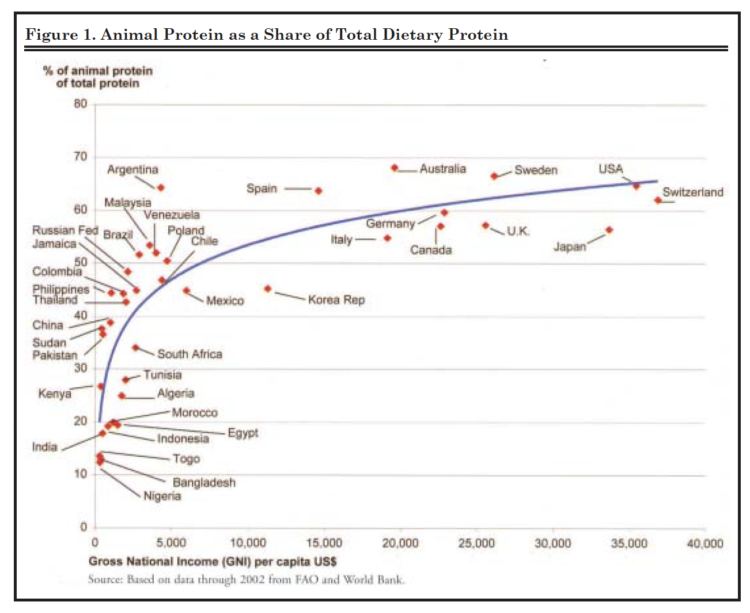

Dietary transition from vegetable to animal protein. Prior to the growth in the energy-driven demand for agricultural raw materials, the exciting longer-term opportunity for U.S. agriculture was the growing demand in the rest of the world for animal proteins. As consumers in China and Asia in general experience growing real incomes, they are beginning to change their diets from a primarily vegetable-based protein diet to an animal-based protein diet. Figure 1 depicts this dietary transition phenomenon. The graph clearly shows that as incomes increase, diets shift more towards animal protein. The current biofuels boom and the increasing costs of energy may or may not be slowing this dietary transition as real purchasing power declines. But, once the biofuels industry matures, will this dietary transition again be the major growth story for agriculture? Or will the demand for these products move to suppliers other than the U.S.?

Globalization of the food system. In the long run, food production can increase significantly in the rest of the world because, in contrast to most of history, global access to both production technology and financial capital has profoundly changed the constraints and unshackled productive capacity and capability in much of the rest of the world. In the U.S., most of the land and water needed for agricultural production is being fully utilized, and allocation of additional land and water resources to agricultural production is highly unlikely. In essence, the “plant” in terms of crop production is operating close to full capacity. This is clearly not the case in much of South America (Brazil, Uruguay, Bolivia, and Argentina) as well as in parts of Eastern Europe, where adoption of new technology and market-driven business models have the potential to dramatically increase agricultural output. U.S. animal production is not constrained by the same land and water resources as crop production, but expansion in the animal industries faces equally limiting constraints with respect to location and siting of livestock facilities and the regulatory permitting process. Most food companies are globally sourcing and selling, and, although transportation and logistics costs are rising, they are unlikely to reverse the trend of increasingly global rather than local production of food products.

In essence, the U.S. will face increasing global competition in a business climate where agricultural production can be expanded more cost effectively in other countries than it can in the U.S. In the longer term, agricultural output is likely to grow more rapidly in the Americas in the Southern hemisphere compared to the Northern hemisphere, and in Europe in the East, including countries of the former Soviet Union, compared to the West.

Figure 1. Animal Protein as a Share of Total Dietary Protein

Demand for local, organic, and sustainably produced foods. While there is a continuing trend towards increased globalization in the food system, there is also an opposing trend towards local sourcing of food and use of less industrial methods for food production occurring at the same time in the United States and throughout the developed world, particularly in Western Europe. This trend is reflected in the rapid growth of organically produced foods and regional food labeling and marketing, along with the development of markets for food grown under “sustainable” social systems or at “fair-trade” values. This trend is also connected to public concern with sustainability in energy use. Issues such as the greenhouse gas emissions and the “carbon footprint” of food production and distribution—including “food miles,” or how far food travels before consumed, and other environmental impacts of industrial food production are attracting increasing attention.

Besides environmental and sustainability concerns contributing to this trend, perceived taste, freshness, and health benefits are also driving the growth in consumer demand for organic or sustainably produced food products. The growth in demand for organic or sustainably produced food offers an opportunity to Indiana producers who may prefer or are more suited to smaller or specialized production practices, as well as to those producers who are committed to the values that underlie this trend.

Growth in exports and the declining value of the dollar. Most analysts expected that the increased use of corn for ethanol production would come at the expense of exports, but in fact that has not been the case. Exports of corn as well as soybeans and wheat have in fact grown dramatically in the past 2 years. The fundamental reasons for that growth are the continued strong economies and purchasing power of China, India, and much of Asia—as well as the declining value of the dollar. The dollar has declined not only relative to currency values for those countries buying our grain products, but it has also declined relative to the currencies of competing exporters of those products. The value of the dollar currently is below the record low levels of the mid-1990s, resulting in prices of agricultural products in importing countries being only modestly higher than 2-3 years ago, when we experienced a much stronger dollar but almost 50 percent lower commodity prices. The growth in personal income and food demand in Asia and foreign exchange rates and currency values will likely determine whether or not the foreign demand for U.S. agricultural products will continue to be strong.

Note however, that the declining value of the dollar is a two-edged sword relative to the agricultural industry. Although a lower currency value increases our competitive ness in selling agricultural products in global markets, it also increases the cost of imports. In addition, an increasingly larger proportion of agricultural inputs are being imported rather than produced domestically. In contrast to 3-5 years ago, when the vast majority of our fertilizer was produced domestically, almost two-thirds of our nitrogen is now imported, and P&K are also increasingly sourced from outside the U.S. borders. The same is true of chemicals for pest control. A significant explanation for the dramatic increase in the cost of production for corn, soybeans, and wheat in the Midwest (a 50 to 60 percent increase in production costs) is the increased dependency on imported raw materials and the higher cost due to increased transportation costs as well as the lower value of the dollar.

The Resurgence of Risk in Agriculture

The business climate and financial outlook for crop agriculture are favorable for the next 1 to 2 years. However, the greatest risk to this sector is the rising cost structure of the industry. In this year alone, production costs for corn (fertilizer, seed, chemicals, etc.) have increased 58 percent. In addition, land values and particularly land rents are expected to increase from 10 percent to 25 percent this year. Thus, while crop prices are very high, the rapid increase in costs of production and land is quickly eroding the increased margins that many producers experienced in 2007. While prices appear to be strong enough in the near term to offset the higher costs of production, the issue is the impact that continued rises in costs of production will have on the producer’s margin risk.

Of course, the increased risk to the livestock industry is challenging as well, with feed costs not only rising rapidly, but the increased volatility in those prices making it much more difficult to budget and plan for feed costs. In addition, livestock producers continue to face increased risks associated with environmental regulations and community discord associated with the externalities of livestock production.

In summary, increased market risk coupled with the increasing risks associated with 1) the overall U.S. economy, 2) relationships with the local community, neighbors, suppliers, and buyers, and 3) the environment has placed new emphasis on the ability of producers to manage risk. In this uncertain environment, there is both increased opportunities to succeed and increased opportunity to fail. How these risks are managed by both producers and the industry as a whole will shape much of the future of agriculture in Indiana and beyond.

The Increasing Strain on Natural Resources

The intersection of increased global food demand and policy are placing unprecedented strain on our natural resources. Most notably, the debate over the use of land for energy crops, food crops, or conservation activities such as the CRP is beginning to heat up. There are a number of concerns over the potential overuse and/or degradation of land resources due to intense farming practices ushered in by higher prices. In addition, pressure even in rural communities is increasing to consider whether rural land is best used for residential and/or recreational uses rather than agricultural uses. Specifically, intense scrutiny is being placed on location of livestock facilities vis-à-vis their potential rural neighbors and other competing uses for the land. Finally, as the demand for alternative uses of the land increases, the value of the land continues to increase as well, making it difficult for young and beginning farmers to enter

farming while helping bolster the balance sheets of those who currently own the farmland.

Land is not the only resource being placed under pressure. Water is a critical resource for direct human consumption, crop production, livestock production, and even biofuel production. While the issue of water is not as intense in Indiana as it is in the western U.S., it will continue to be an increasingly important factor even in Indiana. The other critical resource is clean air. More research is necessary to understand better the externalities from agricultural activities that affect air quality and to design alternatives for managing these externalities.

Ultimately, the policy issues associated with these resource constraints are likely to be: 1) the mix of management, technology, and/or regulation that can/should be used to determine the use of land, water, and air resources; 2) whether those management, technology, and/or regulatory responses are acceptable solutions to the public, and 3) the extent to which the management, technology, and/or regulatory responses are burdensome to the industry’s long-term financial health.

The Role of Biotechnology in Redefining Agriculture

The application of biology through biotechnology has the potential to redefine the role of agriculture for two fundamental reasons. First, biology and biotechnology replace and/or complement chemistry and the mechanical sciences as the fundamental science base for new technological and productivity advances. Many of the technological advances that increased productivity and contributed to growth and overall economic development in the past 50 years have had their science base in the physical and mechanical sciences. These advances will

continue to be important in the future, but more of the science base for future technological advance, productivity growth and economic development is likely to come from the biological sciences. This places agriculture in the mainstream of productivity growth, and economic development in the developed as well as the less developed economies.

The second profound implication of biology and biotechnology in redefining agriculture is that it dramatically expands agriculture’s role as a raw material supplier for a broader set of industries. The agriculture of the past 100 years has been a raw material supplier for the food and nutrition industry and, to a limited degree, the fiber and textile industry. But biotechnology and the advances in biology and biochemistry expand dramatically the potential uses for agricultural products. In fact, some are suggesting that in the future agriculture will be a significant supplier of raw materials for: (1) food and nutrition products, (2) bioenergy and industrial products, including synthetic fibers, plastics, wall coverings, and other products that

have historically been derived from the petrochemical industry, and (3) health and pharmaceutical products. This significant broadening of the economic sectors that will use agricultural products as raw materials increases agriculture’s importance in the overall economy.

The main policy questions surrounding this factor for Indiana are: (1) how quickly will biological breakthroughs come to fruition that dramatically affect crop yields (particularly for corn) in ways that reshape the current tight supply situation? (2) what opportunities, outside of biofuels, provide Indiana agriculture with the best options for diversifying its agricultural economy and capturing more value-added within the state? and (3) where should limited resources be invested to advance these potential opportunities and provide an environment for incubating and growing these opportunities within the state?

Conclusions

The overarching factors highlighted above will significantly affect the long term future of Indiana agriculture. Decision makers in Indiana’s agricultural sector who understand and track these factors are more likely to make better decisions regarding future investments and policy choices. Each agricultural sector in Indiana will also face other important factors specific to those sectors. Sector-specific factors are discussed in the following papers.