Land As An Investment

June 17, 1993

PAER-1993-8

- H. Atkinson, Professor*

Why Buy Land?

In early summer after a shower, the aroma and beauty of a field of corn or beans evoke n many farm people both a sense of nostalgia and expectations of a bountiful harvest. There’s something special about owning this land.

But, aside from personal satisfaction, why do people buy land? Farmers, of course, need land to farm. A high priority is placed by many farm families on land owned as a base of operation — home, storage facilities, and at least some acreage to farm or use for livestock. Even a small base of operation provides permanence and a sense of belonging to the community — factors which may be important in leasing additional land. Farmers may also purchase additional acreage in order to more fully employ their main assets of labor, management and equity capital; however, with a given amount of equity and credit, several acres can be leased for every one that is purchased. This can provide consider-ably more acres to farm and money to spend for family living compared to buying, but the security of tenure is not as strong on leased land.

Land purchase is also a means of investing equity capital for both farmers and non-farmers. Expected returns to investment in land include the annual operating return to land and increases (or decreases) in land values over time.

The non-operator landowner receives an annual return in the form of cash rent or a share of the crops. State-wide rent as a percent of average cropland value was 7.1 percent in 1992 according to the Purdue Land Values and Cash Rent Survey. After paying taxes, insurance and miscellaneous land ownership costs, the net return in 1992 would have been under 6 percent.

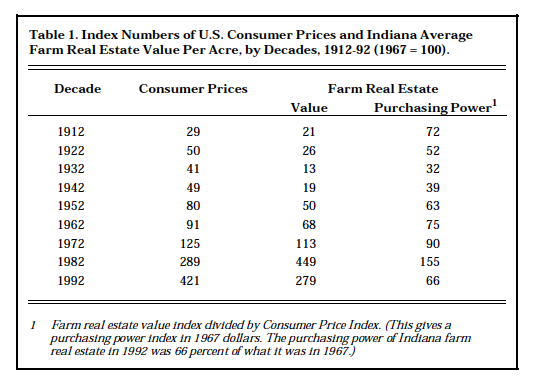

Table 1. Index Number of U.S. Consumer Prices and Indiana Average Farm Real Estate Value Per Acre, by Decades, 1912-92, (1967 = 100)

The Purdue study last year found that cash rent for average quality cropland averaged from 6.6 percent to 7.6 percent across 6 regions of the state.

Many land buyers, both farmers and non-farm investors, accept low annual rates of return because they expect land values to increase over time, at least keeping up with the rate of inflation. And there is some probability that land values will go up faster than inflation, thus resulting in real increases in values. When the expectation of increasing land values (present to some extent in most purchases) becomes the primary concern, the buyer might be termed a speculator, especially if one uses substantial credit for the purchase.

Will Land Values Beat Inflation?

According to USDA estimates, Indiana land values increased by about 13 times from 1912 to 1992, while the 1992 inflation index was nearly 15 times the 1912 figure. Indiana land values didn’t quite hold their own in purchasing power or real value over this 80-year period. But wide differences occurred within this 80-year period in the relationship between land values and inflation (Table 1). Consumer prices rose the first decade of the period, and so did land values but at a slower rate. Then prices fell into the late 20s and 30s, land prices much more than consumer prices, compounding the financial woes of Indiana agriculture during the great depression.

But from that point until 1982 the decade-by-decade increase in land values exceeded increases in the consumer price index. Indiana land prices declined about 38 per-cent from 1982 to 1992, the first decade-to-decade decline in 60 years. Consumer prices rose by 46 percent during that decade so the purchasing power of land dropped by about 57 percent (Table 1). The widely held view that land moves up with inflation was not true during this period! The current purchasing power of Indiana farm land as measured by the Consumer Price index is about the same as in the mid-fifties.

Can Land Pay For Itself?

No, not if reasonable rates are paid for labor, non-land capital, and other inputs. Land is like a bond on which an annual payment is received, and the initial investment is recovered at maturity or upon sale of the bond. In central Indiana, $1500 per acre land might yield a net cash rent of $90, each dollar of which would service a loan of $10.67 if amortized for 25 years at 8 percent interest. The $90 would service a total loan of $960, thus requiring a down payment of $540 per acre or 36 percent for the land to carry itself.

Farmers who buy land to operate may have an annual flow of funds which could be used to supplement earnings solely attributable to land. When estimating the return to land, expenses usually include a charge for operator labor. If family living expenses are being covered by other farming operations or off-farm income, the charge for operator labor could be used for debt service. In the above example this could increase by a third the debt that could be serviced.

In calculating the return to land under owner operation, interest expense on non-land capital is included. If no credit is being used, then this interest charge would be available for debt service, and total debt that could be serviced by all available funds might equal the purchase price. But this doesn’t mean the land is paying for itself; it is being subsidized by labor and equity capital. Furthermore, private institutional lenders usually would not make a 100 percent loan without additional security.

Who Should Own Farm Land?

Land purchase is a risky business for farm operators, especially if substantial credit is used. But it is almost axiomatic that where there is risk of substantial loss, there also is the chance of substantial gain. For example, Indiana land purchased in 1962 would have gained 20 percent in purchasing power or real value by 1972, based on changes in the Consumer Price Index and USDA land value estimates. But with a purchase in 1982, a decline of 57 per-cent occurred by 1992. A 1972 purchase held for a decade would have gained 72 percent, but holding another decade would have resulted in a loss greater than the previous decade’s gain in purchasing power!

One might argue that the farmer who buys land to farm should not be overly concerned with ups and downs in land values. There is truth in this statement if several assumptions are made: 1) Land is financed so that there is little chance of having to liquidate when farm incomes fall and land prices are low, 2) No consideration is given to results which could have been achieved in an alternative investment, and 3) The effect on credit availability due to decreased net worth from lower land values is unimportant. These assumptions tend to fit the older farmer who has accumulated sufficient cash to buy land with little or no credit, has no plans for expansion which would require credit use, and who values the security and other satisfactions which come from owning land.

What are the Alternatives?

What alternatives are available to the younger farmer struggling to pull together the resources necessary for a full-time farming operation? Here are some possibilities.

- Get into livestock production. Each dollar invested in hog, poultry, or dairy production creates more productive employment opportunity than if invested in land. Also consider existing buildings on small acreage which can sometimes be bought for a fraction of new construction costs.

- Use the same or less capital needed to buy one acre, but invest in additional equipment and operating expense to farm several acres of cash or share rented land. The cost per acre of using larger equipment on large acreage may be similar to the cost of smaller machinery on a small acreage, but the operator can cover more acres and would thus expect to earn more for his labor.

- Invest in bigger equipment, and do custom farming in addition to farming rented or owned land. Before buying equipment, line up land owners who want their land custom farmed, and reach agreement on what operations are to be performed and for what price. An incentive payment of a per-centage of the yield or gross sales over a base amount can increase returns to both operator and landowner.

- If you have special skills, consider investing in the equipment and facilities necessary to offer services to neighboring farmers and others. Examples are a well-equipped shop, trucks for custom hauling, equipment for land clearing, terracing, etc., and equipment for spraying or spreading of herbicides, fertilizer, and lime.

For the younger farmers, renting may be the means to future ownership. In parts of the corn belt, nearly half of the farm land is not owned by people who farm it; however, much of this land is in the hands of farm-based folks — retired farmers and their offspring (even grandchildren)— folks who still appreciate the aroma following a summer rain that arises from a field of corn which is as “clean as a whistle,” and who know that there’s something special about owning land.

* Purdue Professor Mike Boehlje made helpful comments which are appreciated.

The settlement of much of our agricultural land was based on the philosophy that those who till the soil should own it and that we should be a nation of family farmers — farmers who are their own bosses and who receive the fruits of their labor. Out of this philosophy has come such institutions as the land grant colleges with their functions of teaching, research and extension; the Farmers Home Administration; and the Soil Conservation Service and other USDA agencies designed to help farmers produce food, fiber, and forest products more efficiently. As a result of this philosophy our agricultural production plant has become the envy of much of the world.