Lysine: A Case Study in International Price Fixing

March 13, 1999

PAER-1999-02

John M. Connor, Professor*

On October 14, 1996 in U.S. District Court in Chicago, Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) company pleaded guilty to price fixing in the world market for the amino acid lysine. In the plea agreement, ADM and three Asian lysine manufacturers admitted to three felonies: colluding on lysine prices, allocating the volume of lysine to be sold by each manufacturer, and participating in meetings to monitor compliance of cartel members (Department of Justice [DOJ 1996]). A corporate officer of ADM testified that his company did not dispute the facts contained in the plea agreement. In addition to precedent-setting fines paid by the companies, four officers of these companies pleaded guilty and paid hefty fines, while four more managers have been convicted and face probable fines and jail sentences for their leading roles in the conspiracy.

The lysine price-fixing episode was one of the largest, best documented, and most important prosecutions in modern times under the Sherman Act of 1890. The lysine cartel was striking in its comprehesive, multinational dimensions. Both the structural characteristics of the world lysine market and the corporate management cultures of the principal conspirators helped facilitate collusive selling behavior for about three years. Antitrust officials have learned how easy it was for four determined companies with sales spanning five continents to organize a highly profitable cartel that could easily have gone undetected. Man-agers of companies will see that the penalties for and chances of being caught fixing prices have escalated as a direct result of the lysine episode. Here I chronicle the operation of the 1992-1995 lysine conspiracy and identify a number of key legal, economic, and management issues raised by the episode.

The Market for Lysine

Lysine, an essential amino acid, stimulates growth and lean muscle development in hogs, poultry, and fish. Lysine has no substitutes, but soybean meal also contains lysine. In the 1960s, Asian biotechnology companies discovered a fermentation process that converts dextrose into lysine at a much lower cost than conventional extraction methods. (Documentation of these and other facts can be found in Connor (1998a) and other publications listed in “For More Information.”) By the 1980s, two Japanese manufacturers were importing large quantities of dextrose from U.S. wet corn millers and exporting high-priced lysine back to the USA. ADM became the largest U.S. manufacturer of lysine in February 1991 and quickly gained about half of the U.S. market. U.S. lysine consumption grew 10 percent per year in the 1990s. The U.S. market reached sales of $330 million in 1995; world sales totaled $600 million.

Archer Daniels Midland

ADM is a large and diversified company. In fiscal year 1995, ADM had consolidated net sales of $12.7 billion (ADM). During 1986-1995, ADM’s net sales had increased by 10.1 per-cent per year. ADM’s major divisions are oilseed and corn starch products. The corn products division produces corn sweeteners, corn starch, alcohols, and a host of biotechnology products. Within the corn products division, fructose and ethanol are mature or maturing industries with slow growth and narrowing margins; however, the other bioproducts from corn generate much higher margins. During 1989-1995, ADM invested $1.5 billion in its bioproducts division.

For a company of its size and diversity, ADM is managed by a remarkably small number of managers (Kilman and Ingersoll). Chair-man Dwayne Andreas and a few top officers reportedly made all major strategic decisions from 1970 to 1997. Until late 1996, the ADM board contained a large majority of current and former company officers, relatives and long standing close friends of Andreas, or officers of companies that supply goods and ser-vices to ADM.

Andreas has built a legendary network of powerful business and government contacts since the 1960s. He was close friends with and contributor to a wide array of farm-state Congressmen and Senators, especially Hubert Humphrey and Robert Dole. Since 1979, Andreas and ADM have contributed more than $4 mil-lion to candidates for national office or their parties. ADM has benefitted greatly from the U.S. sugar program and from federal ethanol subsidies and usage requirements (Bovard).

Economic Conditions Facilitating Price-Fixing

With one or two exceptions, the lysine market exhibits all the eco-nomic conditions that facilitate price fixing. First, market sales concentration was very high. The lysine cartel consisted of four manufacturers that produced 95 percent of the world’s feed-grade lysine. During 1994, ADM alone supplied 48 to 54 percent of the U.S. market. Second, lysine is a perfectly homogeneous product. Third, technical barriers to entry are high. Plants are highly specialized in pro-duction (implying large sunk costs of investment), and their sizes are large relative to market demand. Patents and technological secrecy impede entry. Fourth, market power is difficult to exercise when accurate price reporting mechanisms exist, such as auctions in public exchanges. Domes-tic lysine prices are almost completely hidden from public view. Fifth, lysine purchases were large and infrequent. Animal-feed manufacturers purchased lysine by the ton. Large and lumpy orders are easier for a cartel to monitor for compliance than frequent, small transactions.

Price-Fixing: Chronology & Mechanics

By the late 1980s, Ajinomoto, Kyowa, and one South Korean company, Sewon, were exporting about$30 million of lysine per year to the United States and charging $1.00-$2.00 per pound, much less than U.S. organic chemical companies were charging for extracted lysine. Then, ADM discovered why Asian biotechnology companies were buying so much dextrose from the United States—it is a raw material for lysine made by fermentation. In 1989, ADM committed an initial

$150 million to build the world’s largest lysine factory in Decatur, Illinois and hired 32-year-old biochemist Mark Whitacre to direct the new lysine division. Production began in February 1991, and a “tremendous price war” erupted (Whitacre). The U.S. price dropped from $1.30 in 1990 (or $1.20 in January 1991) to a record low of $0.64 in July 1992. ADM’s cost of production is, reportedly, between $0.65 to $0.70 per pound when the plant is operating as designed. At selling prices near $0.60, ADM was losing millions of dollars per month in its lysine operations. Asian producers were suffering even greater losses per ton.

About this time, the lysine division was placed under ADM V.P. Terrance Wilson. In April 1992, Wil-son and his subordinate Mark Whitacre met with Ajinomoto and Kyowa Hakko in Japan, where they proposed the formation of an “amino acids trade association.” By this time ADM controlled one-third of the world market. In June 1992, the first of many meetings of the “lysine association” took place in Mexico City. The three companies (and later the South Korean company, Sewon) discussed raising prices, allocating production, and setting sales shares across several regions of the world.

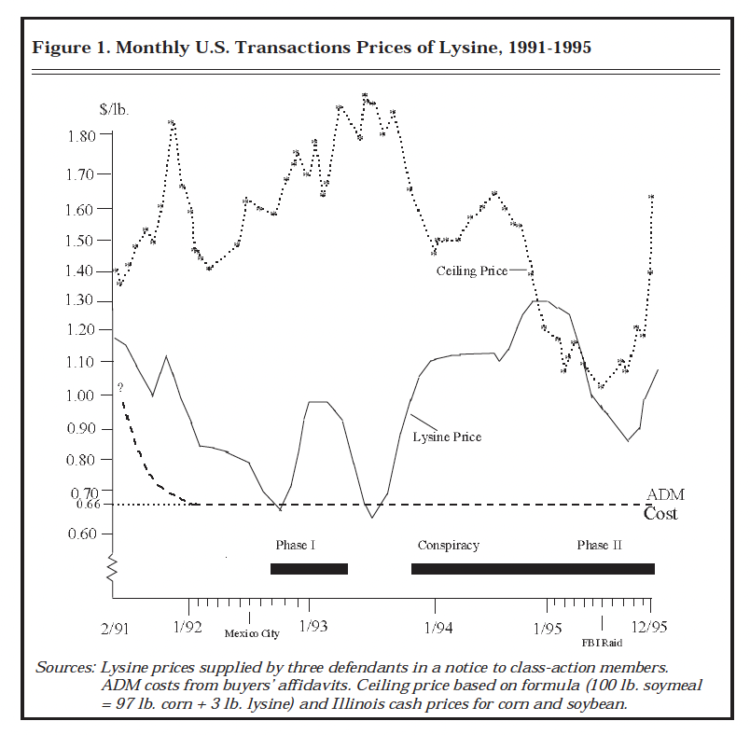

The conspirators apparently were successful in raising the U.S. price of lysine to $0.98 for three months (November 1992 to January 1993). From October 1993 to August 1994, prices held at a steady $1.08 to $1.13 and then rose again to about $1.20 for another six months (Figure 1). Industry output growth was constrained to half its historical rate. A year after the conspiracy ended in late 1995, U.S. lysine exports doubled.

Whitacre was recruited by the FBI as a secret informant (a “mole”) in November 1992. Up until June 1995, he provided hundreds of audio tapes of many price-fixing meetings concerning lysine, citric acid, and fructose. The FBI secretly made additional video tapes of the “lysine association” meetings. A federal grand jury was formed in Chicago in early June of 1995 and obtained subpoenas for all information on price fixing by ADM and its co-conspirators.

Figure 1. Monthly U.S. Transactions Prices of Lysine, 1991-1995

More than 70 FBI agents raided ADM’s corporate offices in Decatur, Illinois on the night of June 28, 1995; many ADM officers were also inter-viewed in their homes that night. Seized documents show 1992-1995 “sales targets” and “actual sales” by all members of the lysine association. Documents were subpoenaed from many other firms as well. In the three following months, ADM’s stock price fell 24 percent ($2.4 billion of market value). At its October 1995 stockholders’ meeting, Chair-man Andreas disallowed discussion of the price-fixing charges. By February 1996, ADM had a total of at least 85 suits filed against it, 14 by lysine buyers and many others by stock-holders claiming mismanagement and failure to divulge material information.

In the spring of 1996, the Department of Justice’s criminal case was beginning to falter. No indictments had yet been filed. The DOJ was targeting (Executive V.P.) Michael Andreas and Terrance Wilson for criminal charges, but not a single ADM officer offered to corroborate the evidence. The Asian companies also refused to cooperate. Moreover, Whitacre’s credibility was tarnished by his own admission that while an FBI mole he defrauded ADM of $9 million.

In April 1996, ADM, Ajinomoto, and Kyowa offered to pay “civil dam-ages” of $45 million to the class of buyers of lysine during 1994-1995. Technically, the three companies were not admitting that they were guilty of price fixing. The class was represented by a Philadelphia law firm that made the lowest fixed-fee bid in an unusual auction held by a U.S. 7th District Court judge. The judge refused to consider bids based on conventional percentage contingency fees. Buyers had three months to decide whether to accept an assured part of the $45 million settlement immediately or to “opt-out” of the agreement and possibly win larger settlements in the future. Based on a damage estimate that was 10 to 12 times higher than the defendants’, 32 large companies did in fact opt out. The judge was criticized for rushing to judgement civil penalties that normally follow the completion of the criminal case. Law firms operating under fixed fees have incentives to settle quickly rather than to wrest bigger settlements through protracted negotiations.

In a shocking setback for ADM, in August 1996 the three other lysine co-defendants “copped a plea.” In return for lenience, the three Asian companies filed guilty pleas, and three of their executives admitted personal guilt and agreed to testify against ADM. Now isolated, ADM’s lawyers began to negotiate in earnest with the DOJ. On October 14, 1996, ADM also agreed to plead guilty to criminal price fixing, to pay a $70 million federal fine for its lysine activities, and to fully cooper-ate in helping the DOJ prosecute M. Andreas and T. Wilson. Numerous changes in ADM’s Board of Directors occurred soon after: M. Andreas was placed on “administrative leave”; T. Wilson resigned; and D. Andreas was relieved of his duties as CEO (though he keeps his title of Chairman).

The criminal fines and civil damages have cost the guilty parties at least $159 million in the case of lysine alone as of late 1997. Legal costs are around $76 million for lysine and other commodities, and shareholders’ suits were settled for$38 million by ADM. The total monetary costs for price fixing, mismanagement, and fraud for all three products (lysine, citric acid, and fructose) are $600 million and rising (Connor 1998a).

Price-Fixing Injuries

The courts have held that price fixing is per se illegal under the 1890 Sherman Act. That is, in a criminal case prosecutors need only prove that an agreement was “beyond a reasonable doubt” made to restrain prices or output; it is not necessary to prove that the agreement was in fact put into operation. A conspiracy to manipulate prices is illegal even if no economic harm can be identified. However, antitrust offenses typically do cause economic harm to many groups: rival firms, buyers, suppliers, employees, shareholders, and other stakeholders. Plaintiffs in a civil antitrust case bear a heavier evidentiary burden of proof than in a criminal case. The plaintiff must prove “with reasonable certainty” that the violation occurred (often using evidence from an earlier criminal proceeding to do so) and that it suffered a compensable harm as a result of the violation. In order to estimate damages, a plaintiff must determine the difference between the revenue actually earned during the period of unlawful conduct and what would have been earned absent unlawful conduct.

Five potential groups may be harmed by price fixing (Page). The first and clearest case of damages involves direct purchasers, who pay an inflated price called the “over-charge.” Buyers who were over-charged have had legal standing to recover three times the overcharge since the first federal price-fixing case was decided in 1906. Lysine overcharge estimates ranged from$15 to $166 million. Second, a portion of the overcharge is passed on to the indirect buyers of products containing lysine. In the present case, hog and poultry farmers who buy prepared animal feeds containing lysine are harmed by both the higher price of animal feed and lost farm sales. Under many state antitrust statutes, indirect overcharges are recoverable in state courts, but since 1977 no standing is given to indirect buyers in federal courts. Several such lysine suits are ongoing.

A third group of buyers may be harmed. If a cartel does not contain all the producers in an industry, nonconspirators (“fringe” firms) may raise their prices toward the cartel’s price. Direct buyers from noncartel sellers are harmed, but under the law only the conspirators are liable to pay damages. Thus, noncartel sellers can enjoy excess profits during the conspiracy period. This type of injury did not apply to lysine because almost all sellers in the world belonged to the conspiracy.

Those forced to buy inferior substitutes or those who reduce their purchases in response to the higher price make up a fourth group harmed by price fixing. Although this kind of harm is well accepted as a social loss by economists and some legal theorists, the parties incurring these “deadweight” losses generally have been denied standing to sue by the courts. Finally, price fixing harms those suppliers of factors of production to the conspirators who lose sales or income due to output contraction. The courts do not usually allow standing for such parties, such as workers forced into unemployment, because the injuries are viewed as indirect or remote.

Normally a civil class-action suit is settled after the conclusion of the government’s case. The lysine story is more complicated because the civil class-action suit was settled a month prior to the criminal pleas. Settling the class-action suit early gave ADM two enormous advantages in its legal strategy. The criminal guilty pleas could not be entered as evidence in the class-action case, nor could the size of the criminal fines be used as a guide to settling civil damages.

Penalties for Price Fixing

Parties guilty of criminal price fixing are sanctioned by means of fines and imprisonment. The ADM affair signaled a significant escalation in price-fixing fines. A major change in price-fixing penalties came in 1975, when Congress upgraded antitrust crimes from misdemeanors to felonies. Under 1991 federal sentencing guidelines, any felony can be punished by fines equal to twice the harm suffered by victims. Up to 1975, the maximum monetary expo-sure of corporations was three times overcharges plus $1 million; since 1995, the exposure has risen to five times the overcharges, almost a 60-percent increase.

The first application of the “two-times” felony rule in 1995 resulted in a $15 million fine for one company. The second time this rule was invoked was in October 1996, when ADM was fined $70 million for the lysine conspiracy and $30 million for its leading role in the citric-acid conspiracy. However, the DOJ explicitly rewarded ADM with a discounted fine because the company had agreed to cooperate in prosecuting other companies as well as two of its own officers (M. Andreas and T. Wil-son)**. The Asian lysine producers received even larger discounts because they agreed to cooperate with prosecutors two months before ADM did. The size of the discount awarded to the lysine producers for their good behavior is not known, but could be as high as 50 percent. In addition, the DOJ agreed to forgo prosecuting ADM for its role in the potentially larger corn-sweeteners case. Thus, the $70 million lysine fine is at most a minimum indicator of the true overcharges incurred by buyers of lysine.

Given ADM’s share of the lysine market, one can infer that the total overcharge on direct buyers of lysine was at least $65 million, but it could have been as high as $140 million. Sales of lysine during the conspiracy were about $495 to $550 million, so the conspiracy raised U.S. lysine prices by 12 to 28 percent above the competitive price.

Implications for Producers

Lysine is one of 20 essential amino acids necessary for muscle and bone development in monogastric meat animals. Hogs and poultry cannot manufacture lysine on their own, so it must be ingested. Wheat and corn have traces of lysine, but soy meal is quite rich in lysine. When soybean prices are high and corn prices low to moderate, a corn-lysine mix is much cheaper than an equivalent amount of soy meal. During 1991-1995, a typical 97-lb.-corn-3 lb.-lysine mix was cheaper than 100 lb. of Midwest soy meal more than 90-percent of the time.

Experts say that a growing pig needs on average about 22 grams of lysine per day for optimal growth. According to Pete Merna of the Illinois Pork Producers’ Association, a typical Corn Belt pork producer that utilizes 100 tons of feed per year would have to buy, directly or indirectly, about 3 tons of lysine. During the height of the lysine conspiracy in 1994, that lysine would have cost farmers or feed manufacturers $7,200, which was almost double ADM’s cost of making lysine. Most farmers had no choice but to pass on the $3,600 in extra costs to the packers***. When lysine prices shot up in mid-1992 and again in mid-1993, producers not under contract would briefly incur profit reductions. In a few months, the higher feed costs would cause the typical producer to reduce feed use and delay hog marketings. The delay would cause prices offered to rise enough to cover the higher feed costs. Producers under contract to packers pass cost increases through immediately. In addition, because of a small rise in retail pork prices, the quantity demanded decreased. Some pork producers were forced to cut back on production when lysine prices were artificially inflated. By my rough estimate, farm revenues from hog sales declined by $15 to $20 million during the conspiracy.

But the greatest injury was to producers and feed companies that were overcharged some $65 to $140 million for the lysine they bought during the conspiracy. By a curious twist in federal antitrust law, only direct buyers of lysine can sue for the treble damages due to them. Michigan and 15 other states allow indirect buyers to sue for price-fixing damages under state antitrust laws. To put it in a nutshell, if a pork producer mixes his own feed or lives in Michigan, he is entitled to get triple damages ($11,000 in our example) from the lysine makers. But if the producer buys pre-mix and lives in Indiana, he has no right to sue.

Final Observations

The lessons for public policy and managers of multinational agribusiness firms are profound. A statement of U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno on the day ADM pleaded guilty said in part “This $100 million criminal fine should send a message to the entire world” (DOJ). Measured by the widespread attention of the world’s business press and by the sharp reaction of ADM’s stock prices, she is certainly right. The lysine settlements demonstrate that the cost of discovered price fixing has suddenly gone up. Moreover, the chances of being caught are now higher than ever (Bingaman). Dozens of investigations of international price fixing have since been launched by federal authorities, and a new era of multilateral coordination among the world’s antitrust agencies has begun (Connor 1998b).

The antitrust agencies have rea-son to monitor wet-corn millers closely for price fixing. Lysine and citric acid are but two of a long list of synthetic organic chemicals now being made by ADM and other wet-corn milling companies. The rapid growth of specialty chemicals made from corn starch is partly the result of entry of wet-corn millers into the traditional synthetic organic chemicals industry, which had sales of nearly $100 billion in 1995. These products include food ingredients (such as sorbitol), feed ingredients (tryptophan), and medicinals (ascorbic acid). For most specialty organic chemicals, only one to three domestic producers are active. For example, in 1994 ADM was one of at most three U.S. manufacturers of lactic acid, sodium lactate, and sodium gluconate. As wet-corn millers continue to move into these specialty chemical markets with their high sales concentration, the opportunities for price fixing will increase.

The lysine conspiracy resulted in far-reaching changes in ADM’s governance structure and leader-ship. Three of ADM’s officers were convicted on criminal charges, and more are under indictment. The ADM board of directors has been transformed. Up to 1995, the great majority of the 17 board members were insiders by anyone’s definition. In 1996, eight insiders on the board resigned, but not all their replacements pleased the stockholders. A resolution by institutional shareholders of ADM that would have imposed stricter guidelines in selecting out-side directors nearly passed at ADM’s 1996 annual meeting. In April 1997, Dwayne Andreas relinquished his title of CEO to his nephew G. Allen Andreas.

Antitrust prosecutors tend to tar-get companies like ADM that lead their industry. Targeting high-profile companies is a wise use of con-strained administrative resources because it increases the deterrence effect. Moreover, the DOJ imposed sanctions on ADM that have markedly changed the rules of the price-fixing gambit. Since 1996, price fixers have faced public penalties and private damages that are five times their illegal profits, far higher than their previous exposure. If the “two-times” rule for fines is fully applied, then patient private plaintiffs will have a clearer guide to the treble damages they may seek.

Perhaps the most important les-son of the lysine conspiracy for anti-trust enforcers is the ease with which an international cartel was formed and executed. The two smaller lysine producers claimed that they were coerced into joining the cartel by leaders ADM and Ajinomoto, and leaked tapes of the price-fixing meetings corroborate the charge (Eichenwald). With just two or three top managers from each company attending meetings around the world every three months, the conspirators were able to arrive at complex allocations of production from at least six plants, exports from three countries, and sales to five continents that were, if not optimal, highly profitable. The cartel hung together in the face of gyrating and uncontrollable soybean and corn prices and a presumptive cultural chasm between ADM and its three co-conspirators. Were it not for a well placed whistle-blower, the lysine cartel might still be in full operation today.

Because it was an international conspiracy, overcharges as large as those in the United States were very likely incurred by buyers of lysine in other parts of the world. In

mid-1997, antitrust authorities in the European Union and Mexico opened duplicative investigations of lysine price fixing. The multinational character of the lysine conspiracy underscores the need for multinational legal approaches (Connor 1998b). Recent court decisions make it clear that U.S. authorities can seek redress from off-shore conspiracies that affect U.S. trade or domes-tic commerce. However, effective national prosecution is unlikely unless the target companies own significant assets in the affected nation’s territory. Bilateral antitrust protocols have been signed and for-mal annual meetings have recently begun among the U.S., Japanese, European Union, and other antitrust agencies, but so far cooperation is limited to gathering and sharing of information. It is difficult to envisage a legal structure that would permit multilateral prosecutions of international cartels.

For More Information

Bingaman, Anne K. The Clinton Administration: Trends in Criminal Antitrust Enforcement, Speech before the Corporate Counsel Institute, San Francisco, California, November 30, 1995 (http://www.usdoj.gov/atr/public/speeches/speech.n30).

Bovard, James. Archer Daniels Midland: A Case Study in Corporate Welfare, Policy Analysis No. 241. Washington, DC: The Cato Institute (September 1995).

Connor, John M. Archer Daniels Midland: Price Fixer to the World, Staff Paper SP 98-01. West Lafayette: Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University (January 1998a).

Connor, John M. The International Convergence of Antitrust Laws and Enforcement. Review of Antitrust Law and Economics (forthcoming 1998b).

DOJ. Archer Daniels Midland Co. to Plead Guilty and Pay $100 Million for Role in Two International Price-Fixing Conspiracies. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. (http://www. usdoj.gov/atr/public/press_releases/1996/508at. htm)

Eichenwald, Kurt. “The Tale of the Secret Tapes: Bizarre and Mundane Mix at Archer Daniels.” New York Times (November 16, 1997): 3-13 of Section 3.

Kahn, E.J. Supermarketer to the World: The Story of Dwayne Andreas, CEO of Archer Daniels Midland. New York: Warner Books (1991).

Kilman, Scott and Bruce Ingersoll. Risk A Verse. The Wall Street Journal (October 27, 1995): A1.

Page, William H. (editor). Proving Antitrust Damages: Legal and Economic Issues. Chicago, Ill.: Section of Antitrust Law, American Bar Association (1996).

Whitacre, Mark. My Life as a Corporate Mole for the FBI. Fortune (September 4, 1995): 52-68.

Kilman, Scott and Bruce Ingersoll. Risk A Verse. The Wall Street Journal (October 27, 1995): A1.

Page, William H. (editor). Proving Antitrust Damages: Legal and Economic Issues. Chicago, Ill.: Section of Antitrust Law, American Bar Association (1996).

Whitacre, Mark. My Life as a Corporate Mole for the FBI. Fortune (September 4, 1995): 52-68.

__________

* Dr. Connor assisted a few lysine buyers in estimating the overcharges they may have incurred as a result of the conspiracy. All statements of fact in this paper are based on publicly available materials, and all opinions expressed are Dr. Connor’s own and not necessarily those of any party or lawyer involved in the legal proceedings discussed in this paper. An earlier version of this article appeared in “Choices” magazine in 1998. The author thanks Jay Akridge, Mike Boehlje, Peter Barry, Lee Schrader, Chris Hurt, and anonymous reviewers of “Choices” for their constructive comments. Purdue Journal Paper No. 15439.

* These two were found guilty in District Court in Chicago in September 1998.

*** When lysine prices shot-up in mid-1992 and again in mid-1993, producers not under contract briefly incurred profit reductions. In a few months, the higher feed costs would cause supply to contract. Eventually prices of hogs would rise enough to cover the higher feed costs. Producers under contract to packers pass cost increases through immediately.