Making Farm Credit Decisions

August 17, 1994

PAER-1994-09

Michael Boehlje, Professor and J. H. Atkinson, Professor

Many farmers and other business managers value the advantages of a long term relationship with lenders who supply their operating and intermediate term credit. These advantages come mainly from the lender’s increasing knowledge of the borrower and the business, and may include quicker action on loan applications, larger or more flexible lines of credit, and additional financial services. Because of these advantages, borrowers are not inclined to go “rate shopping” very often for a small reduction in the short term interest rate.

However, this may not be true for farm mortgage loans. Small differences in rates or other loan features can cause big differences in costs over the life of a long-term loan. Furthermore, there may not be much contact between the borrower and lender after the loan is made unless the same lender is used for all types of credit. Thus, farm mort-gage borrowers are more likely to do some “rate shopping”.

Loan Terms and Rates Vary

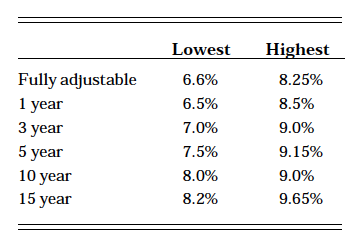

Differences do exist among various farm real estate lenders according to a recent straw poll of 30 lenders in Indiana. Information was obtained on rates as of May 1, 1994 for fully adjustable loans and those with fixed rates of 1, 3, 5, 10 and 15 years (note: none of the commercial banks reported 15 year fixed rates). Life insurance companies tended to have the lowest rates and banks the highest. Farm Credit Services reported on their highest quality loans and had the lowest rate for the fully adjustable loan but the highest for 10 and 15 year fixed rates. Following are the highest and lowest rates as of May 1 (rates probably have gone up around a percentage point since then).

Table 1.

But interest rates don’t tell the whole story! All the insurance company lenders had a minimum size loan, ranging from $75,000 to $1 mil-lion. None of the other lenders had minimums. All the insurance companies had a loan closing charge (these are charges in addition to abstract, appraisal and other service based fees), usually around 1% of the loan. About half of the other lenders had a fee or charge. Some lenders refer to these charges as “points” with each point being 1/100 of a percent. Some lenders offer a rate without points or a fee and will lower the rate if the borrower pays points. This is actually an interest pre-payment or interest buy down. Computer programs are available which will calculate the annual percentage rate including points. As a rule of thumb, borrowers should consider buying down their rate if they have the cash to do so and if they can recover the initial fee (or points) during the first few (3-5) years of the loan or prior to the interest reset period or early loan payoff. Finally, only two lenders offered the entire range of payment options.

Selecting Fixed vs Adjustable Rates

Farmers who are negotiating new loans face the tough decision of choosing a rate which is subject to change or which is fixed for a stated number of years. Farm real estate loans often are amortized over a longer period of time than the number of years during which the rate is fixed. For example, the term of a loan may be 20 years. If a 3 year fixed rate is chosen, the rate is subject to change at the end of each 3 year period. The borrower may or may not be able to select a different fixed rate period after the initial decision.

Three-fourths of the lenders surveyed placed “caps” on their adjustable loans. Here’s an example reported by a bank: on a one year fixed rate loan, the maximum annual adjustment is 1 percent and the maximum over the life of the loan is 5 percent. In some cases, the rate terms might be chosen as much to obtain the periodic reset and life-time caps associated with the rate as for the rate itself. For example, assume the current rate on adjustable rate mortgages is 7.0 with annual reset caps of 1.0 percent and a lifetime cap of 5.0 percent above the initial rate. With a positively sloped yield curve, if the one year fixed rate is above 8.0 percent and rates are generally rising, the adjust-able rate with a 1.0 percent annual reset cap would likely be lower than the new one year or longer term fixed rate a year from now. So the adjustable rate might be chosen in part to buy the annual reset cap. In a similar fashion, the 5.0 percent life-time cap will have more value as a maximum upper limit on rates if it is tied to a lower initial rate.

How Long to Fix Rates?

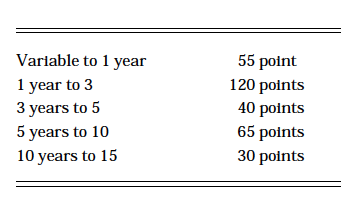

In choosing a period over which to fix rates, farmers have to answer two questions. First, are rates going up or down; that is, where are rates likely to be at the end of the fixed rate period? For example, a Farm Credit Services borrower on a variable rate can change to a fixed rate at any time. Suppose the difference from one term to another is as follows:

Table 2.

With a variable rate of 7 percent, fixed rates for 1, 3, 5, 10 and 15 years would be 7.55 percent, 8.75 percent, 9.15 percent, 9.8 percent and 10.1 percent respectively. If borrowers assumed that the variable rate would rise to 8 percent over the next year, then perhaps they should “lock in” the 7.55 percent for a year. But then the 1 year rate might rise 1 percent to 8.55 percent. Should they at that time switch back to a variable rate? They are forced now to make an assumption about the level of rates at the end of the second or third years. Assume they believe that interest rates will drop during the 1996 presidential election year. With a 120 point spread between 1 and 3 years, they may rule out a fixed rate for 3 or more years, a decision which is further fortified by their assumption that a recession may develop in 3 or 4 years. The conclusion may be that there’s likely to be little difference between the 2 year cost of a variable and a 1 year fixed rate so they stay with the variable rate.

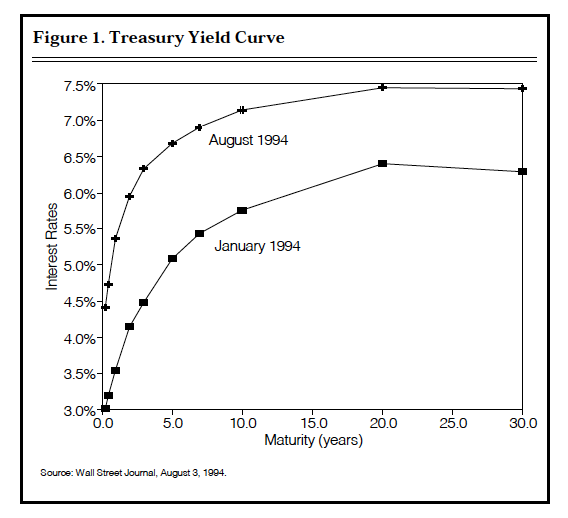

The second question that must be answered is what will happen to the spread in rates over different maturities; will the yield curve flatten or steepen? Figure 1 shows the changing shape in the yield curve (as well as the change in rates) on government bonds in mid-summer 1994 compared to six months earlier. Note that rates have increased, but more for maturities of 1 to 5 years than for 3 month or 30 year debt. Although Figure 1 indicates a recent “flattening” of the yield curve on government securities, this may not be true of a specific lending institution’s farm mortgage rates. For example in May, 1993, one lender in the survey had only a 50 point higher rate for a 3 year fixed rate compared to a variable rate. In May, 1994 the 3 year fixed rate was 175 points higher than the variable rate for that same lender. But to go from 3 year to 5 year fixed rates, the rate increase was reduced to 40 points from 70 points a year earlier. The remainder of this lender’s yield curve was fairly flat in both years. So this lending institution steepened its yield curve on the shorter maturities and flattened it on the longer maturities. The important message here is to check with individual lenders and try to get an idea of their perspective of expected changes in rates for different maturities rather than rely on yield curves as reflected by government bonds.

Figure 1. Treasury Yield Curve

How might this changing shape of the yield curve influence a decision? If the spread between, say, 1 and 3 year maturities is abnormally wide (i.e., a steep slope to the yield curve) and rates are expected to decline, one might want to choose a variable rate and then lock in rates on a longer term basis when the yield curve flattens. If rates are expect to rise, the decision is more complex — if short term rates are expected to rise while longer term remain constant, then stay with short term rates and ride the curve up (i.e. there is no advantage of locking in longer term rates now). If both short and long term rates are expected to rise, then the short run savings of staying short must be com-pared to the additional costs that are incurred in the longer run by not locking in rates over the maturity of the loan.

The current interest rate outlook is much like the last situation. both short and long term interest rates are generally expected to rise slowly and the yield curve may flatten further, increasing the complexity of selecting a fixed rate period. A simpler solution may be to choose a

“reasonable” rate in terms of cash flow and historical levels, then lock in that rate for the longest period possible.

Some Points to Remember

- Interest rates do vary among lenders

- Be sure to shop not just rates, but also for terms.

- Calculate the true cost of the loan including all add ons.

- The choice between fixed or variable rates and the length over which to fix a fixed rate depend upon the yield curve and interest rate expectations.

1994-95 Outlook Meetings

Purdue extension economists will present the agricultural outlook for 1994/95 at 34 meetings around the state of Indiana between September 13 and 22. Check with a Purdue Cooperative Extension Service office in your county or watch for local announcements for meeting details.

Speakers will review the supply, demand, and price situation for major commodities and will discuss other factors affecting the food system during the year ahead and beyond. The dramatic change from the short crop of 1993 to prospects for near record production in 1994 provide the setting for another interesting marketing year. Meetings have been scheduled in the following counties. Adams, Benton, Boone, Cass, Clinton, Dekalb, Fayette, Fulton, Greene, Hancock, Howard, Huntington, Jackson, Jasper, Johnson, Kosciusko, Madison, Montgomery, Newton, Owen, Parke, Porter, Posey, Pulaski, Putnam, Rush, Shelby, Steuben/Lagrange, Sullivan, Tippecanoe, Warrick, Wayne, Wells and White.