Marketing Sustainable Beer

October 7, 2020

PAER-2020-16

Authors: Aaron J. Staples, ; Carson Reeling, Assistant Professor; Nicole Olynk-Widmar, Professor, Associate Department Head, and Graduate Program Chair; Jayson L. Lusk, Distinguished Professor and Department Head of Agricultural Economics

Brewing beer is a water- and energy-intensive process that generates a tremendous amount of solid waste, both in the form of spent grain and recyclable material. Commercial and regional brewers are increasingly investing in environmental sustainability equipment that reduces input use, operating costs, and environmental impacts. These technologies incorporate different aspects of environmental sustainability, including water use and wastewater reduction, energy use reduction and decreased carbon emissions, and increased landfill diversion or solid waste reduction.

Sustainability investments often require high costs that can prohibit access among many smaller breweries, such as microbreweries and brewpubs. One potential solution is to market sustainability initiatives through labeling or social media campaigns to communicate a commitment to sustainability. If a small brewery could differentiate their product through environmentally friendly marketing, then they could potentially attract new consumers to their product—or charge a small premium for their product—making these investments less risky.

There is reason to believe beer buyers would be willing to pay a premium for sustainably produced beer, as demand for environmental sustainability attributes in food has increased in general. Our recent study determines which U.S. beer buyers value sustainability attributes in beer and places a dollar figure on their valuation.

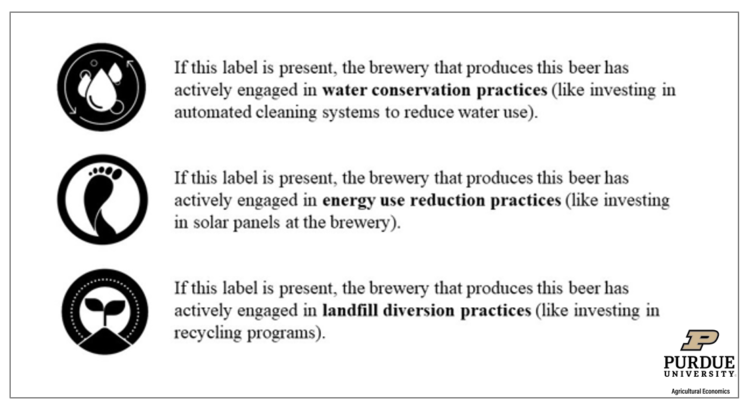

We used a hypothetical experiment to estimate the value U.S. beer buyers have for sustainable beer. We presented a sample of beer buyers with pictures of multiple, hypothetical six-packs and asked them to select the one they were most likely to buy (Figure 1). The six-packs varied in primary packaging (aluminum cans or glass bottles), price, whether the beer was “locally brewed” or not, and three sustainability attributes. The three sustainability attributes included water conservation practices, energy conservation practices, and landfill diversion practices. Incorporating multiple dimensions of environmental sustainability allowed us to determine which sustainability factors consumers value most. We created eco-labels to indicate the presence of each sustainability attribute on the six pack (Figure 2). We repeated the experiment over multiple rounds comparing different combinations of beer attributes. Doing so allowed us to observe the trade-offs buyers make between the different attributes. For example, are you willing to pay $1.50 more for a locally brewed beer with water conservation practices? Or do you prefer the non-local beer in glass bottles at the lower price?

Figure 2. Ecolabels indicating the sustainability attributes present on a given hypothetical beer in our experiment

Who is willing to pay for sustainable beer?

We expected that not all beer buyers were willing to pay a premium for sustainable beer. We therefore asked respondents to describe themselves (their age, income, education levels, and so on), state their beer consumption habits, and offer their general attitudes towards sustainability. We were able to split beer buyers into three groups based on their personal characteristics and which six-packs they selected in the experiment.

Group 1 (36% of beer buyers) and Group 2 (39% of beer buyers) comprise higher-income, younger adults ($100,000 +). Group 1 is the youngest age group, composed primarily of beer buyers aged 21–24. Group 2 buyers are predominantly aged 25-44. Buyers in Group 3 (25% of beer buyers) are the oldest.

Importantly, Group 1 and Group 2 also enjoy buying new beers and are more likely to recycle in their household. While variety-seeking is much more common amongst the craft beer community, where 80% of craft beer drinkers in our study stated they enjoy trying new beers as opposed to just 40% of commercial only buyers, craft and commercial drinkers were found throughout all three classes. Household recycling was also more common in Groups 1 and 2, potentially indicating that these beer drinkers hold higher sustainability preferences.

Our results suggest that Groups 1 and 2—younger, higher-income beer drinkers who enjoy trying new beers and recycle in their household—demand sustainable beer and are willing to pay a premium for these products.

What are consumers willing to pay for sustainable beer?

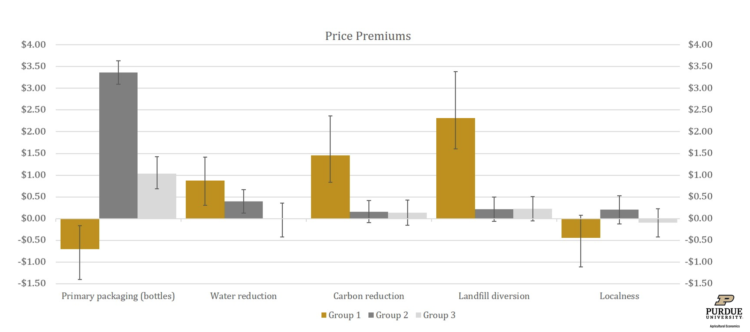

Figure 3 depicts price premium—or the dollar amount beer buyers are willing to pay—for different beer attributes for each group. The height of the bars indicates the average premium for each attribute. The error bars indicate 95% confidence interval. Note that if a confidence interval encompasses both positive and negative values—that is, the error bars cross over zero—we cannot say with confidence that the premium is different from zero.

Group 1 (36% of beer buyers) has the greatest preference for environmental sustainability in beer. Average premiums for water sustainability, energy sustainability, and landfill diversion practices are $1.45, $2.08, and $2.31 per six-pack, respectively. This group also prefers aluminum cans, which are thought to be a more environmentally friendly form of packaging; the negative average premium on primary packaging in Figure 3 implies consumers are willing to pay $0.70 less on beer packaged in glass bottles relative to cans. Localness, which we define here as the beer being “locally brewed,” is not significantly different from zero. (This is also the case for Groups 2 and 3. We discuss potential explanations for this later.)

Group 2 (39% of beer buyers) has weaker preferences for environmental sustainability in beer. These consumers are only willing to pay an average premium of $0.40 per six-pack for water sustainability practices—much less than the $1.45 premium estimated for Group 1. Group 2 prefers glass bottle packaging, placing a significant premium on glass bottles at $3.36 per six-pack. Greater preference for glass bottles is consistent with weaker preferences for carbon and landfill diversion sustainability attributes, as glass bottles are heavier to transport and more difficult to recycle. Nonetheless, Group 2 is indeed willing to pay a small premium for beer brewed with water sustainability practices.

Finally, Group 3 (24.5% of beer buyers) is not willing to pay any premium for environmental sustainability attributes in beer. The only premium Group 3 is willing to pay is for glass bottle packaging, with an average premium of $1.04 per six-pack.

Marketing Implications

Our results suggest that there is considerable consumer demand for sustainable beer, as approximately 75% of beer consumers are willing to pay premiums for beer brewed using environmentally sustainable practices. These consumers are, on average, younger, higher-income beer buyers who enjoy trying new beers and are more likely to recycle.

Our findings are important for brewers, and potentially other alcohol producers, seeking to differentiate their products in highly competitive industries. With over 8,000 craft breweries in the country, making your product stand out among the seemingly endless options has become increasingly difficult. Marketing sustainability efforts through eco-labels or environmental graphics could be a potential means of product differentiation and increased sales.

Although labels can inform consumers of sustainability habits directly at the point of sale, getting consumers to engage with labels can be a challenge. Fortunately, we find the beer buyers most likely to pay premiums for environmentally sustainability attributes in beer are also the respondents who stated they enjoy purchasing new beers. In other words, these are variety-seeking beer buyers, a trait commonly seen amongst the craft beer community. Labels could serve as an effective marketing strategy for variety-seeking consumers as this group is already likely engaging with can or bottle design, beer style, alcohol content, bitterness, and other characteristics when making purchasing decisions. When a variety-seeking beer buyer enters a retail outlet in search of a new beer, they will consider an array of potential purchasing alternatives before making their choice. If they have never purchased a beer in consideration before, they are forced to rely on the information presented to them on the label, including the brand, the beer style, and so on. Incorporating sustainability into can or bottle label design would be a low-cost way for craft brewers to differentiate their product, provide valuable information at the point-of-sale, and appeal to variety-seeking, sustainability-minded beer buyers.

Limitations

We identify two limitations to this study. The first is that this study is purely hypothetical, and thus these results could serve as an upper limit on the price premium consumers are willing to pay for these attributes. Nonetheless, the positive price premiums discussed above are a preliminary indicator of consumer preference for sustainability attributes in beer.

The other limitation is regarding the insignificance of “Locally Brewed” beer. There are three potential explanations for this result:

- We never explicitly defined localness in our experiment, which may have caused respondents to disregard this attribute and focus more on the relatively better-explained sustainability attributes.

- We asked respondents to envision that each six-pack is their favorite style of beer. Instead of envisioning a style of beer (e.g., lager), a respondent may have envisioned a brand of beer that they know is not locally brewed (e.g., Bud Light) leading them to disregard the localness label.

- A similar study, Hart (2018), argues that consumers are willing to pay a premium for local beer when the beer is not of their usual style, but the premium vanishes when the beer is of their preferred style. In other words, the style of the beer matters more than the localness attribute when the consumer is buying their favorite style, which was the exact design of our experiment. Thus, we are not ready to dismiss the idea that consumers do not value locally produced beer.

It is also important to remember that many smaller craft breweries already rely heavily on local consumption. Furthermore, our results suggest variety-seeking drinkers—a common trait amongst the craft community—are more likely to pay premiums for sustainably brewed beer. This could suggest that improved marketing of sustainability habits could complement the localness branding, leading to further product differentiation and attracting a wider consumer base.

In Summary

Sustainability investments in the beer industry are costly and can limit access among smaller breweries. However, marketing initiatives through eco-labeling could make the investment worthwhile. We find positive price premiums attached to sustainability attributes, showing that marketing sustainability efforts could be an effective way for breweries to attract new beer consumers, or to charge a premium for their product. Water sustainability practices generate the largest share of consumer interest at a modest premium, while a smaller portion of consumers are willing to pay larger premiums for landfill diversion and carbon reduction practices. Our hope is that with this knowledge, breweries will be better equipped to handle sustainability investment decisions, continue to reduce their environmental footprint, and market their sustainability efforts to U.S. beer drinkers.

Related Report: Staples, A.J., Reeling, C.J., Widmar, N.J.O., Lusk, J.L. (2020). Consumer willingness to pay for sustainability attributes in beer: A choice experiment using eco-labels. Agribusiness, 1-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21655

References

Brewers Association (2020). National beer sales & production data. Available at Brewers Association website: https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/

Hart, J. (2018). Drink beer for science: An experiment on consumer preferences for local craft beer. Journal of Wine Economics, 13(4), 429–441.