Machinery Replacement: Tax Implications of Trading vs. Sale-Purchase Options

November 16, 1991

PAER-1991-14

George F. Patrick, Extension Economist

Many farmers replace machinery and equipment by trading in their old machinery. The gains or losses realized on these trades are not recognized for tax purposes. However, selling the old asset and purchasing the new machinery may minimize after-tax machinery costs for some farmers because of self-employment (SE) tax considerations. This article develops guidelines for the least cost alternative of machinery replacement versus trading in. Farmers must be in a sole proprietorship or partnership to benefit from the sale-purchase option, and benefits are larger for lower income individuals.

Tax Treatment of Trade-Ins and Sale-Purchase of Machinery

The tax consequences of trade-ins and sale-purchase options for machinery replacement may be quite different. This difference arises, in part, because income for income tax purposes is not necessarily the same as earnings for self-employment tax purposes. There may also be differences in the timing of when income is reported and expenses are deducted.

It is assumed that the assets are property used in a trade or business to avoid unnecessary complications. For the trade-in option, it is also assumed that the transaction involves “like kind” assets and unrelated parties. Assets are of like kind if they are of the same nature or character. Sales in the salepurchase option are assumed to be to a third party to avoid any implications that the sale and purchase transactions are linked.

Trade-Ins of Machinery

If a trade consists solely of one property for another of like kind, such as machinery for machinery, no gain or loss is recognized. The new asset acquired is treated as a continuation of the old property and takes over the basis of the old. If boot is paid, the basis for depreciation of the acquired property is the basis of the old property plus the boot paid. There is no distinction as to whether the acquired property is new or used.

For example, a farmer trades a used tractor with an adjusted basis of $8,000 for a new tractor. The dealer gives a trade-in allowance of $20,000 for the old tractor and the farmer pays $30,000 boot. The $12,000 gain on disposition of the old tractor is not recognized. However, the basis for depreciation of the new tractor is only $38,000. Under the MACRS 150% declining balance method for farm machinery, $4,070 of depreciation would be allowed with the half-year convention in the year of trade. Depreciation in future years would be calculated on the $38,000 basis. The depreciation allowed would reduce both income for income tax purposes and earnings for self-employment tax purposes each year.

Sale and Purchase of Machinery

The sale of used farm machinery may involve a gain or loss. If the property is sold for more than its adjusted basis, there is a gain. This gain is treated as ordinary income to the extent of depreciation allowed or allowable on the property. Any gain in excess of the recomputed basis is capital gain income and subject to a maximum federal income tax rate of 28%. Although the depreciation recapture and capital gain income are reported as income for income tax purposes, they are not earnings for self-employment tax purposes.

For example, if the old tractor from above is sold for $20,000, there is a gain of $12,000 for income tax purposes in the year of sale. If the depreciation allowed or allowable were equal to or exceeded $12,000, the entire gain would be ordinary income because of the depreciation recapture. If the depreciation allowed or allowable had been $9,000, then $3,000 of the gain would be reported as capital gain income. Neither the depreciation recapture nor the capital gain income would be included as earnings from self-employment.

Section 179 Expensing

A farmer may elect to treat all or part of the cost of qualifying property acquired by trade or purchase as an expense rather than a capital expenditure. Farm machinery and equipment is qualifying property. The Section 179 expensing is limited to a maximum of $10,000 per taxpayer. The deduction is phased out if qualifying property in excess of $200,000 is placed in service in a tax year. The deduction is also limited to the taxable income from the conduct of an active trade or business during the year. In the case of a trade-in of machinery, the Section 179 expensing cannot exceed the boot paid.

After-tax Cost of Options

The trade-in versus sale-purchase options of machinery replacement can be compared in terms of their after-tax cost This after-tax cost can be represented as the capital investment minus the discounted income tax savings and minus the discounted self-employment tax savings. The preferred machinery replacement strategy would generally be the option with lower after-tax cost.

Capital investment in the sale-purchase option is the purchase price of the replacement machine. The purchase price, minus any Section 179 expensing, is the basis for computing depreciation. For the trade-in option, the capital investment is represented by the boot paid pl us the net sales price which could have been realized if the old machine had been sold. However, the basis for depreciation of the new asset is the boot paid plus the adjusted basis of the tradein, minus any Section 179 expensing. If Section 179 expensing is elected, the amount is assumed to be the same for both options.

Depreciation for each option is computed using the MACRS 150% declining balance method for seven-year property. The self-employment and income tax savings are computed by multiplying the relevant marginal tax rates by the depreciation deduction each year and any Section 179 expensing. One-half of the self-employment tax savings multiplied by the marginal income tax rate is subtracted from the income tax savings to account for the deductibility of self-employment taxes in computing taxable income.

For the sale-purchase option, the additional income tax due-from the sale of the old machine is computed. This is the net sale price minus the tax basis of the old machine multiplied by the marginal income tax rate. The net sale price is defined as the gross sale price received minus the expenses of sale. If the basis exceeds the net sale price, the loss generates an income tax credit in the computation.

The self-employment tax savings and income tax savings are discounted to the current time period to determine their net present value. Subtracting the net present value of the tax savings from the capital investment gives the aftertax cost of each replacement option. The present value of any change in social security pension benefits is not considered.

Tax Management Guidelines

For this example, it is initially assumed that the purchase price of the new machine is $50,000 whether trading or buying outright The trade-in allowance and net sale price of the old machine are the same, $20,000, and the time discount rate is 10%. The marginal income tax rates and marginal self-employment rates are assumed constant for the eight years in the period being analyzed. Under these assumptions, the after-tax costs of replacing a machine by the trade-in and sale-purchase option are the same, if the basis of the trade-in is the same as the trade-in allowance.

Five income and self-employment tax situations are assumed to analyze the effect of tax rates on the two options. Situation one assumes a 0% marginal income tax rate and a 15.3% self-employment tax rate. This represents a farmer who has positive earnings for self-employment taxes, but whose federal taxable income is not greater than zero. (A family of four could have an adjusted gross income [AGI] of $14,300 in 1991 and a federal taxable income of$0.) Situation two assumes a combined federal, Indiana, and county marginal income tax rate of 19.4% and self-employment tax rate of 15.3% (an AGI of $14,300 to $48,300 for a family of four in 1991). Situation three assumes a combined marginal income tax rate of 32.4% (AGI over $48,300) and a self-employment tax rate of 15.3% (self-employment earning of less than $53,400). This situation could be common for farm families in which the spouse has an off-farm job. Situation four assumes marginal tax rates of 32.4% for income taxes and 2.9% for self-employment taxes.

This represents a situation in which self-employment earnings exceed $53,400 but are less than $125,000and AGI is from $48,300 to $98,450. Situation five represents self-employment earnings of over $125,000 and an AGI of over $98,450 with combined marginal tax rate of 35.4%.

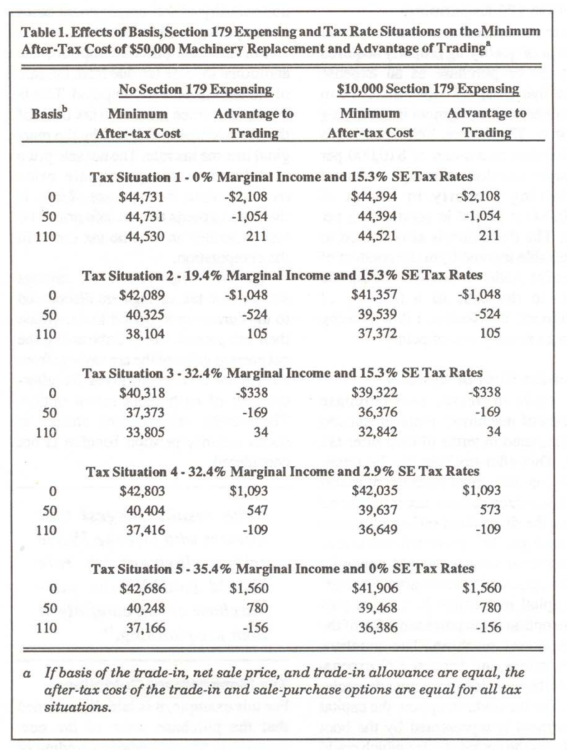

The minimum after-tax costs of replacing a $50,000 machine and the dollar advantage to trading for a variety of tax situations are summarized in Table 1. Three situations of tax basis were considered. The old machinery could be fully depreciated, zero basis; have a basis equal to 50% of the tradein/sale value; or have a basis which was 110% of the trade-in/sale value. Three major conclusions can be drawn from this example:

- The sale-purchase option of replacing machinery decreases after-tax costs for farmers whose earnings from self-employment face the 15.3% rate, if the basis in the old machine is less than its net sale value. The lower the basis, the greater the advantage to the salepurchase option.

- The trade-in option decreases aftertax cost for farmers whose earnings from self-employment exceed $53,400 in 1991, unless the basis of the trade-in is greater than its net sale value.

- Section 179 expensing does not affect the trade-in versus sale-purchase option decision.

- Section 179 expensing only slightly reduces the after-tax cost of replacing machinery. These effects are larger at higher levels of total tax rates.

Table 1. Effects of Basis, Section 179 Expensing and Tax Rate Situations on the Minimum After-Tax Cost of $50,000 Machinery Replacement and Advantage of Trading

Changes in the discount rate, which are not considered in Table 1, can affect the strategy which results in the lowest after-tax costs of machinery replacement Considering only those cases in which the basis of the old machine is less than or equal to its net sale value, the effects of changes in the discount rate were analyzed. For tax situation two, the 19.4% marginal income tax rate and 15.3% SE tax rate, the sale-purchase option had the lower after-tax cost for all discount rates of22% or less. In contrast, for tax situation four, the 32.4% marginal income tax rate and 2.9% SE tax rate, the trade-in replacement option has the lower after-tax cost for all discount rates of 3 % or more. For tax situation four, a marginal income tax rate of 32.4% and the 15.3% SE tax rate, the break-even discount rate was about 12.3%. Lower after-tax costs occurred with the trade-in option for discount rates above 12.3% and with the sale-purchase option for discount rates below 12.3%.

Some “imperfections” may characterize the trade-in and sale-purchase options of replacing machinery, even if the economic bottom line is the same. The “true” trade-in allowance given by a dealer may not equal the net sale value of the old machine for the farmer. The purchase price of a replacement machine may be different if a trade-in is involved. These imperfections may create additional difficulties assessing replacement via the trade-in versus sale-purchase option.

Additional analyses were performed for a variety of situations. Neither the low income nor very high income situations were affected by minor imperfections. Imperfections tended to reduce the differences between the sale-purchase and trade-in options for the other three tax situations.

Conclusions

The results suggest that farmers who face the 15.3% self-employment tax rate should consider the sale-purchase option carefully in their tax planning. The sale-purchase option is more attractive in situations in which the tax basis of the old machine is lower. Lower time discount rates also favor the salepurchase option. Farmers in many circumstances will find that consideration of both the self-employment and income taxes will lead them away from routinely trading in when replacing machinery. However, the “hassle and inconvenience” of selling their used machinery, as well as finding a buyer with money, may more than offset a small penalty associated with trading machinery for some farmers.