Passing the Farm’s Management to the Next Generation

April 23, 2012

PAER-2012-03

Amber Remble, Graduate Student, Roman Keeney and Maria Marshall, Associate Professors

The past century has brought dramatic change in agriculture, a sector that features a relatively small percentage of farms producing the majority of output. This change and the increased scale of operation have implications for how to organize management of farms. Retirement of farmers who were not followed by a direct successor is a leading factor contributing to farm consolidation. Expansion of on-going operations is largely driven by this release of acreage following a family’s exit from farming. In this respect, intergenerational succession on farms and how that process is managed become an important concern for understanding a number of issues, including increasing scale in agricultural production, drivers of farm structure in the U.S., and best practices for succession in farm management.

What We Looked At

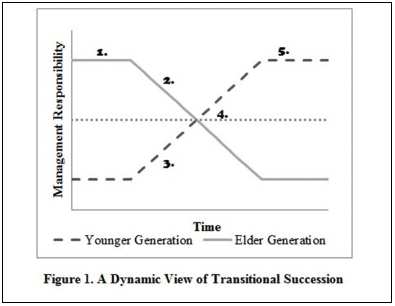

Researchers often treat the succession decision as a full exit/full entry decision, with the succeeding generation wholly replacing the previous generation at a designated time. However, succession takes place over time for most operations, often with an extended period of time in which individuals from different generations jointly manage the farm. The execution of this apprenticeship period during which management is gradually transferred is a function of both the ability of the younger generation to take over the managerial responsibilities of the farm and the impending retirement of the elder generation.

Figure 1 illustrates a possible transition of management responsibility over time between the elder and younger generations of family members. Initially, the elder generation bears all managerial responsibility (1.). Over time, the elder generation has a declining share of managerial responsibility (2.). This can occur because the elder generation relinquishes certain managerial tasks or through expansion of farm enterprises providing managerial opportunity for the younger generation. This increasing presence in the share of the farm’s management is indicated in the dashed line tracing the role of the younger generation (3.). This process continues until, eventually, the younger generation’s role in decision making eclipses that of the senior person (4.). Eventually, the elder generation reaches a full retirement state, and the younger has sole responsibility for managing the farm. Figure 1 offers a generic perspective on a process that requires planning in both business and family contexts.

Figure 1. A Dynamic View of Transitional Succession

The timing of the younger generation’s movement toward being the primary manager will differ due to characteristics and goals that are unique to each farm family. Research in the area has focused on the planning and process of farm asset transfer for understanding motivations to sustain a family farm. Our research differs from this planning perspective and maintains that it is equally important to understand how managerial responsibility is passed on in practice if we are to inform farm families of best practices for insuring successful transition of a family farm across multiple generations.

We accomplish this by focusing on survey data for farms that currently have two operators from different generations (age difference of 20 years or more). The data for each of these farms includes a response by the family as to which generation (elder or younger) is appropriately designated as the primary operator. This allows us to conduct analysis of farms at various points in the succession process depicted in Figure 1.We use statistical analysis of these survey responses to investigate factors that are correlated with families operating the farm with either the senior or junior generation as the primary manager.

The survey data for the analysis are from the 2002 Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) collected by USDA. In simplest terms, we sort the responses into two groups based on the generation with the primary management role and use a statistical model that estimates the influence of a number of factors on whether the family has chosen to maintain primary management with the senior generation or pass that role onto the younger generation. At the time of the survey in 2002, seventy-two percent of the farms reported that the older operator was the primary manager on multi-generation farms.

What We Found

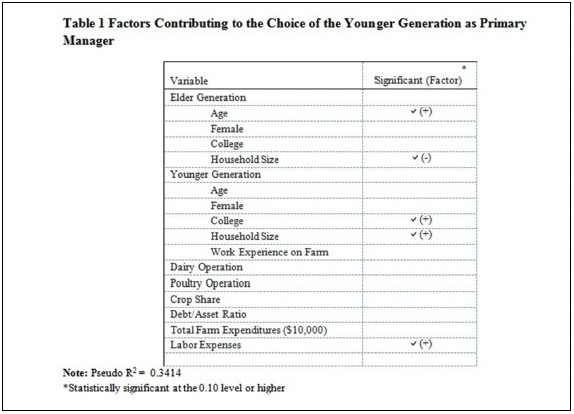

We looked for the factors that had resulted in the younger generation taking over the primary management role. Results are shown in Table 1. The first column gives the factor description. The second column reveals whether the factor had a positive (+) or negative (-) impact on the transfer of management.

Table 1. Factors Contributing to the Choice of the Youngest Generation as Primary Manager

Increasing age of the senior generation increased the chance that the farm had passed on the majority of managerial duties to the younger generation. This is consistent with an elder generation reducing their involvement and passing more duties to a successor. This may play out in a number of ways as authority is given to the person most active on the farm and the senior generation takes on a more advisory role. This relationship is expected because elder farmers reaching retirement are more likely to focus on non-physical work activities and on planning for the future of their farm and estate. The finding is consistent with the lifecycle of the farm business, which indicates that farm operators achieve peak productivity at middle age due to both physical and human capital accumulation. Beyond this peak, farm productivity gains tend to wane for a variety of reasons, including the process of an older generation establishing a set of standard practices. Younger generations may then bring innovative technologies or strategies that help keep productivity gains high.

An interesting finding is that younger generation individuals who obtain college degrees are more likely to be serving as the primary manager on the home farm. While higher education has long been noted as a means for farm children to gain career options and increase earning ability, the complexity of modern agricultural markets, policies, and technology are also factors driving those who choose farming as a career to invest in higher education.

Mechanization of U.S. agriculture has contributed to a reduction in the average farm family size. We investigated how family size might relate to the transition of primary management from senior to junior generations and found that an increase in the number of individuals living in the seniors’ household decreases the chance that management has transferred to the younger generation. Perhaps older generation operators are less likely to retire if they still have dependents living in the household who rely on their income.

Having more children in the young-generation household increased the likelihood that transition of the primary management role had already occurred for the younger generation. This would be consistent with the income demands that additional family members bring in the younger generation. Indeed, the increased income demand and ability of the younger generation’s family to supply labor to the business may be one of the most important factors driving expansion of the farm business, with the younger generation adopting new enterprises that use both farm capital and family labor resources.

The only financial indicator that proved statistically significant in the model was labor expenses for the farm. We found that farms with higher labor expenses (relative to their gross income) are more labor intensive and have more tendency to feature the younger generation in the primary management role. Farms that are labor intensive require a large time allocation to labor oversight, which may encourage a quicker transition of management to the younger generation.

Other variables shown in the table were explored, but did not have a statistical impact on the intergenerational transfer of management.

Concluding Remarks

The results of our analysis confirm the importance of family and individual characteristics in farm succession planning and execution. Economists have had a tendency to look at input and outputs, financial organization, and a number of other business strategies to present guidelines for farm transfer and succession. Our findings indicate that knowledge and productivity embodied in the skill and experience of the two generations are much more critical to the design of a successful transition. Similarly, family demands for income and earnings shares may be strong drivers of the succession process and distribution of farm returns to the different generations’ management resources. This and the importance of family household demands on timing of succession mean that in addition to the apprentice effects (e.g., gained experience, farm specific training) that occur during the period of joint management, it is critical for both generations to use this period to discuss their expectations for planning and implementing a profitable management transition on the farm.