Sources of Information For Large Cornbelt Farmers

March 17, 1993

PAER-1993-4

Gerald F. Ortmann, Associate Professor, University of Natal, South Africa; George F. Patrick, Professor, Purdue University; Wesley N. Musser, Professor, Pennsylvania State University; Howard Doster, Associate Professor, Purdue University.

Farmers’ demand for information has increased in recent years with increased market instability, more complex production technologies, and greater need for financial planning and control. A variety of sources, including consultants in various areas, have the potential to be providers of information on production practices, marketing strategies, and financial analysis.

This article reports on a survey of participants in the 1991 Top Farmer Crop Workshop that obtained estimates of expenditures on and subjective ratings of various information sources including consultants. The Top Farmer Crop Workshop is a three-day program which provides an update on crop economics and production technology as well as allowing participants to analyze alternative technologies using a linear programming model of their own farm. A questionnaire was mailed to participants about three weeks before the 1991 Workshop and participants were asked to bring the completed questionnaires to the Workshop. Eighty usable questionnaires were received.

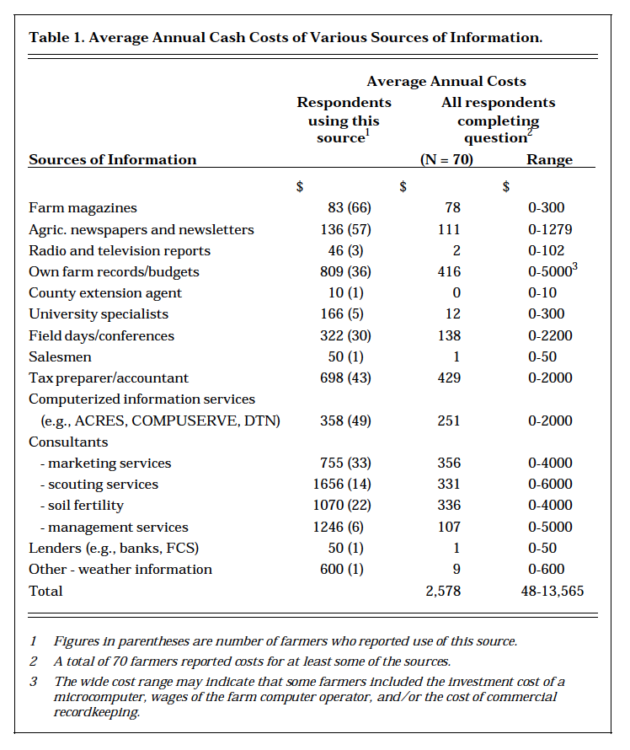

Table 1. Average Annual Cash Costs of Various Sources of Information

Respondents were from eight states, with 48 percent from Indi-ana, 26 percent from Illinois, 14 per-cent from Ohio, and six percent from Iowa. The remaining farmers were from Missouri, Kentucky, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania. The aver-age farmer operated 1,820 acres with 850 acres in corn and 652 acres in soybeans. These crops represented about 73.6 percent of the 1990 gross farm income. Only 23 per-cent of the farms had gross sales of less than $250,000 and 35 percent exceeded $500,000. The average age of the respondents was 39.7 years and they had completed an average of 14.9 years of schooling. Participants in the Workshop were younger, had more years of schooling, and operated larger farms than the average farmer in the eastern cornbelt.

Workshop participants were requested to provide the annual out-of-pocket costs for each information source. The various sources of information and the average annual cash costs of each are reported in Table 1.

Respondents had a wide range of expenditures on information sources. Because these are cash costs, they do not include the opportunity cost of a farmer’s time to acquire the information. On average the respondents spent $2,578 per year on information. The range was from $48 to $13,565, with a median of $1,625. The average expenditure is more than ten times the $217 spent by a sample of Ohio fruit producers in 1987. However, the substantial difference may be due, in part, to the procedure used to obtain the cost information. In this study, the cost of each information source was requested separately, a process which is likely to encourage recall of all expenditures.

Expenditures for farm magazines and agricultural newspapers and newsletters were reported by the largest number of farmers, 94 and 81 percent, respectively, of the 70 responding to the question. How-ever, consultants, including tax preparers, accounted for a large proportion (60 percent on average) of total information costs. Some 70 percent of those responding used computerized information services at an average cost of $251.

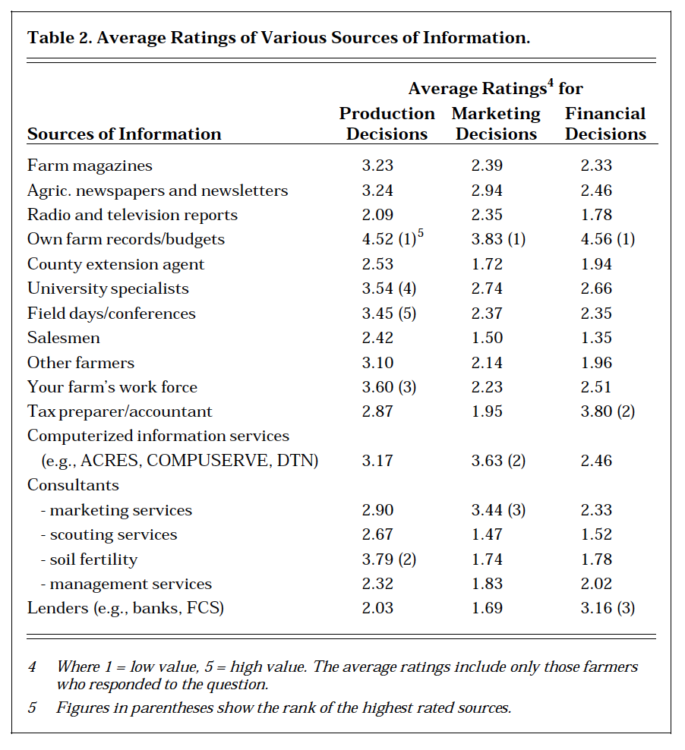

Workshop participants were also asked to rate the value of various sources of information for making production, marketing, and financial decisions with scales ranging from one (low) to five (high).

The average ratings by respondents of various sources of information for making production, marketing and financial decisions are reported in Table 2. Their own farm records/budgets were given the highest rating (4.52) for production decisions, which also was the case for marketing (3.83) and financial (4.57) decisions. These farmers clearly rely heavily on their farm records and budgets for making decisions.

For production decisions, eight other sources of information were also rated above 3.00. The most highly ranked include soil fertility consultants (3.79), the farm’s work force (3.60), university specialists (3.54) and field days/conferences (3.45). County extension agents and salesmen were rated relatively low, 2.53 and 2.42, respectively. The number of highly rated information sources may reflect the complexity of the production decisions. Soil fertility, chemical use, tillage, varietal selection, machinery selection, and enterprise combination are some of the concerns in this area.

For marketing decisions, relatively few information sources were rated highly, and ratings were generally lower than for production decisions. Farm records/budgets were rated highest (3.83), followed by computerized information services (3.63) and marketing services consultants (3.44). All other information sources had ratings of less than 3.00, with agricultural newspapers and newsletters at 2.94, and university specialists at 2.74.

Table 2. Average Ratings of Various Sources of Information

Marketing decisions for commodities such as corn and soybeans are, in large part, decisions involving timing. Fewer alternatives may be considered in the marketing area than in the production area. In addition, the respondents rated their marketing management skills lower than their other management skills, thus they may perceive smaller benefits from marketing information. Only a few of the information sources considered are viewed as potentially useful for marketing decisions, and apparently they do not provide critical information for farmers.

For financial decisions, only three sources of information were rated above 3.00. Their own farm records/budgets were rated highest (4.56), followed by the tax preparer/accountant (3.80) and lenders (3.16). Perhaps even to a greater degree than for marketing, farm finance decisions involve judgments with respect to the future. The sources of information rated highly in making financial decisions provide largely historical information that may be useful in helping farmers evaluate their current situations. As a result, most of the information sources considered in this study are conceivably not viewed as especially useful for financial decisions.

These results are somewhat different from those reported by earlier studies of all farmers. A study of Ohio farmers found that salesmen were ranked first for production information, followed by general farm magazines, specialized farm magazines, and the Cooperative Extension Service. For marketing information, radio reports were ranked highest, followed by general farm magazines, commercial newsletters, and specialized farm magazines. Brokerage firms, lenders, tax preparers, and accountants did not have a major influence on marketing decisions of cash grain farmers. The lender was ranked as the most useful source of financial information, followed by the accountant, tax preparer, and general farm maga-zines. In general, “other farmers” were rated highly. Their own records/budgets were not included as a source of information in this study.

A study of Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, and Georgia farmers indicated that farm magazines, other farmers, and family and friends had the overall highest ratings as information sources. Private and cooperative firms were the primary sources of information for the sales of farm commodities and input purchases. Family and friends were most important in cropping decisions, while lenders were most important for investment and credit decisions. They also found county extension personnel relatively unimportant, except for Conservation Reserve bid decisions.

Differences between the Top Farmer Workshop survey and other studies are probably related to the size of farm operations and the educational level of the farmers. Larger farm operations would be able to spread the costs of obtaining information across more units of production. Consultants received high ratings in this study. This specialized management information that might not be available from other farmers, personnel in agribusiness firms and general farm magazines would have a higher return for these farmers because the scale of their production. The higher educational level of these farmers would facilitate their use of this more specialized information.