State Branding Programs for Indiana Food Products: Consumer and Food Industry Response

August 17, 1995

PAER-1995-10

William Schiek, Assistant Professor; Joseph Uhl, Professor; and Daniel Williams II, Graduate Assistant

Many farm groups have attempted to improve the price they receive for farm products through promotion efforts. These are termed “generic promotion” since they advertise a broad commodity rather than a specific product. There are several national programs designed to raise funds for the promotion of specific commodities. Examples of national generic promotion programs are beef, pork, milk and dairy products, soybeans, and eggs. Promotion of specific commodities has also been carried out at the state and regional level by state promotion boards, state and federal marketing orders, and producer trade associations.

Many states have also begun to promote their agricultural and food products under a common theme or brand. The goal in this case is to increase consumer awareness of and demand for the state’s food products, thereby increasing returns to the state’s farmers and food marketers. Example of these programs are New Jersey’s “Jersey Fresh” promotion, Ohio’s “Ohio Proud” program, and Wisconsin’s “Something Special From Wisconsin.” While such pro-grams are in place in at least 23 states, in most cases little is known about the impacts of such programs or their likelihood of success. Would Indiana benefit from a statewide food promotion program?

There are a number of potential benefits from such a program. Among these are increased producer pride, improved consumer information, Indiana product quality enhancement, and perhaps higher prices for Indiana producers if demand for their products is stimulated. We have been studying the desirability and feasibility of a state-wide promotional program for Indi-ana-sourced food and agricultural products. To determine the attitudes toward the establishment of such a program in Indiana, surveys were conducted of Indiana consumers, food retailers and wholesalers, food processors and manufacturers, and agricultural producer trade associations. An additional survey was developed and sent to administrators of non-Indiana state-sponsored food promotion programs to deter-mine how such programs were developed, funded, and administered.

About 500 Indiana consumers were interviewed in late 1994 by telephone and questioned about their opinions regarding Indiana food products and a potential state-wide branding program. A mail questionnaire was sent to all Indiana food retailers, processors, and producer groups, with 56 retailers, 54 food processors, and 11 producer groups responding. All surveys were conducted in November and December 1994.

What Consumers Say

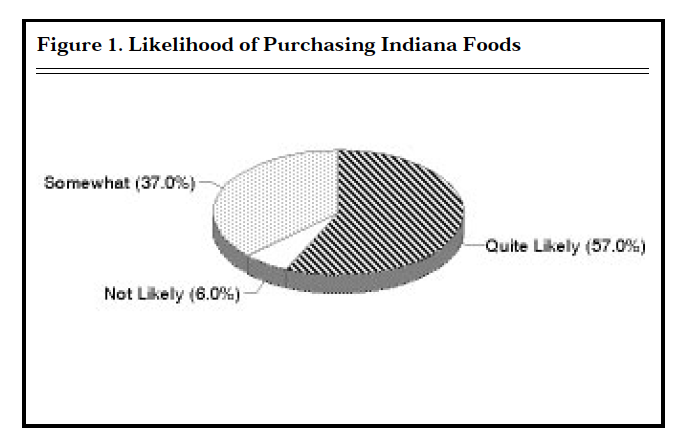

The consumer survey showed that consumers think food freshness, quality, and the brand are the most important factors influencing their purchase of food products. The fact that a product was produced in Indiana was not, in itself, an important criteria for deciding which products to purchase. However, almost 94 percent of Indiana consumers indicated that they would be quite likely or somewhat likely to purchase Indiana-produced products when shopping for food (Figure 1), and their desire to purchase Indiana foods when dining out was almost as strong (87 percent). A majority of consumers felt that both the price and the quality of Indiana food products were about the same as those of other states. Consumers were also asked what they would expect to pay for Indiana products. Assuming quality equal to that of other states’ products, 44 percent of Indiana consumers would expect to pay a price that was about the same as that of other states’ products. An additional 52 percent of consumers expected to pay less for Indiana products. If the quality of Indiana products were higher than those of other states’ products, about 30 percent of consumers would be willing to pay more for Indiana products, 50 percent would pay about the same, and 20 percent would still expect to pay less for Indiana products.

Awareness of the availability of Indiana products was highest for perishables such as fresh fruits and vegetables, dairy products, and bakery products and was lower for bever-ages, meat products, snack foods, and frozen or canned vegetables. Most Indiana consumers indicated that they would purchase an Indi-ana product rather than another state’s product unless the other state had a strong “brand image” associated with the product, such as California Wines.

Figure 1. Likelihood of Purchasing Indiana Foods

There were some demographic factors that influenced the likelihood of consumers to purchase Indiana products. In general, consumers were more likely to buy Indiana products if they had high incomes and they were longtime residents of Indiana. Consumers were less likely to buy Indiana products if they had higher levels of education and if they were brand loyal. The consumers’ location within the state and the degree of urbanization in their place of residence had no impact on their likelihood to buy products from Indiana. Consumers who thought that Indiana products were of higher quality than those of other states were also more likely to purchase Indiana products.

In general, we would conclude that there is some consumer support for an Indiana promotion program, but such support is conditional on Indiana products delivering the quality that consumers have become accustomed to from other states. Because freshness and quality are the most important criteria for selecting products, the state should include these themes in any promotion program in addition to “state pride” or “help the local economy” themes. Finally, while a statewide promotional program might increase total sales of Indiana products, there is little evidence that it alone would increase producer prices and income.

Food Business Managersʼ Opinions

A majority (65 percent) of the Indiana food trade respondents indicated they would support a statewide food promotion program; about 19 percent would be highly supportive. Only about 14 percent of the trade indicated they would be opposed to a state promotion pro-gram. In addition, more than half of the retailers who responded indicated that they would handle more Indiana-sourced products if they were available. About half the retailers also indicated that they currently cooperate with individual agricultural commodity groups on generic promotion efforts.

Who Benefits

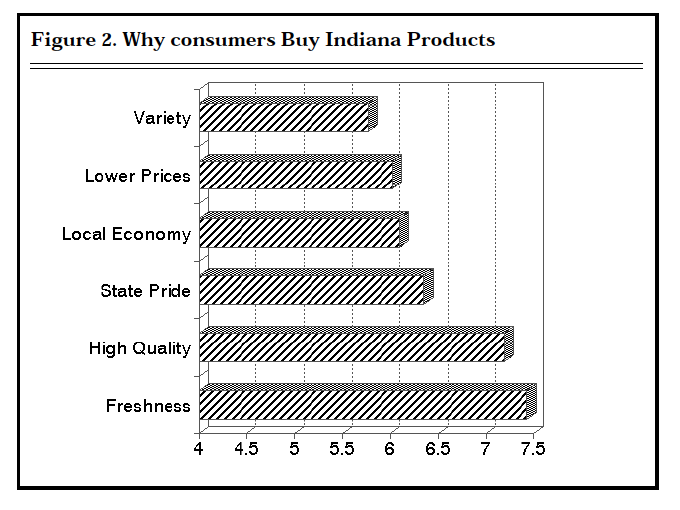

From the trade’s perspective, a statewide branding program would be more successful in increasing sales of Indiana products and improving the perception of product quality than at increasing the prices received for Indiana products. Their perception was that farmers as a group would benefit more than any trade group, while consumers would benefit the least from promotion program. The trade believed that the greatest motivation for consumers to purchase Indiana-produced products was freshness, followed closely by perceptions of higher overall quality (Figure 2). Not surprisingly then, the trade felt that perishable products (fresh fruits and vegetables, meat and poultry, dairy products and eggs, and bakery products) would see the greatest increase in sales as the result of a state food pro-motion program, while nonperishable products, especially beverages and snack foods, would benefit to a much lesser degree.

Program Design and Administration

Difficulty in obtaining financial support from the state or trade and industry groups were viewed by the Indiana trade as the most likely problems facing a statewide promotion program; followed by difficulty coordinating assembly and distribution of state products. The most favored funding mechanism appeared to be some type of voluntary producer or trade association funding. Trade groups showed little support for any type of mandatory funding mechanism. The trade was less supportive of both state government (taxpayer) funding and funding through a fee for using a state-sponsored promotion logo. The Indiana trade was opposed to mandatory producer funding (checkoff program) and to funding through state licensing and registration fees.

Figure 2. Why consumers Buy Indiana Products

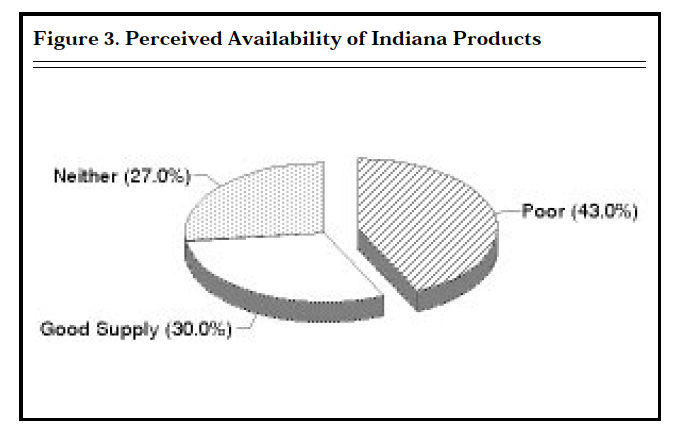

Many managers felt that provisions for state quality control standards, registration of participating companies, and establishing a directory of companies selling Indiana-sourced products would be desirable in a statewide promotion program, although almost a third of the respondents felt that state quality control standards would not be desirable. A majority of the trade respondents deemed a state brand or logo to be important or essential to the success of a statewide promotion program. Significant numbers of managers also felt that media advertising and point of purchase materials would be essential. Based on previous experience, respondents felt that the availability of Indiana-sourced products was a potential problem (Figure 3). Agricultural producer groups in the state may need to work at improving both the actual supply availability and the information about available supply if a state-wide promotion program is to be successful.

We can conclude Indiana food business managers would be supportive of the concept of a state promotional program, and there would likely be substantial trade cooperation with such a program. It is seen as a producer-oriented program which would mostly benefit the fresh food producer. While the managers believe the program may increase quality perception and sales, it will not necessarily raise the prices of Indiana products. Managers favor voluntary producer financing to mandatory or trade financing. Some form of quality control would be needed for the program. The trade survey findings generally agree with and reinforce the findings of the consumer survey.

Thoughts from Other States

Previous studies identified 23 states with statewide food promotion pro-grams run through state departments of agriculture. Responses were received from all but two of these states’ program administrators. The most common objectives of these programs are to increase sales of the state’s agricultural products and increase returns to the state’s agricultural producers. The most critical problems facing the development and administration of a program are obtaining and maintaining funding, and coordinating the supply of agricultural products. Program administrators stressed the importance of maintaining funding beyond the initial years of the pro-gram, otherwise the consumer awareness and excitement generated are lost and must be rebuilt. Maintaining awareness is viewed as less costly than a cycle of funding lapses followed by large outlays to get the program going again.

Most of the funding budget is allocated to three areas: media advertising, trade shows and

point of purchase promotions. Administrators viewed point of purchase promotions as the most effective at impacting the consumer. In-state food processors were viewed as benefiting most from these programs, while the greatest support for the programs came from consumers.

In each of the responding states, participation in the state’s promotion program was voluntary. To date none of the state programs had faced any legal challenges. Several of the states had programs with some type of quality standards or quality control. State administrators suggested that to be successful, a state food pro-motion program should have a clear mission statement (i.e. understand what the program goals and objectives are), keep bureaucracy to a minimum, and obtain input and participation from all parties in the food marketing system. They suggested that the program needs be viewed as something that has benefits for everyone and not just producers.

Conclusions

There is interest on the part of producers, consumers and the food trade in developing a statewide brand identification program for Indiana food products. Such a pro-gram has potential for increasing sales and the image, but not necessarily prices, of Indiana grown and processed foods. A state branding program not only could increase consumer awareness and preferences for Indiana foods but also might stimulate beneficial producer organizational and quality control efforts.

The program would require much more than just developing and promoting an Indiana slogan or logo. To be successful, there would need to be a coordinated effort among producers and food marketing firms in developing reliable and adequate sources of supplies to meet the merchandising needs of today’s food trade. Food quality control standards would also be necessary to insure the integrity of the Indiana product and maintain customer loyalty. The program would require a long-term commitment on the part of producers and the trade in order to produce lasting results. State government may be a catalyst in organizing and financing the program.

Figure 3. Perceived Availability of Indiana Products

There would appear to be three important considerations in designing and implementing an Indiana food branding program. First, this self-help program should be developed and administered by the producers and food trade so that maximum participation in a voluntary program will be encouraged. Secondly, the program should be customer-oriented, with the goals of providing information and better quality food products for consumers. Third, the self-financing of the pro-gram must be fairly shared among the producers and trade, and it must be sufficient and reliable to produce long-term market results.

An Indiana food branding pro-gram will not solve all of the problems of our food industry. However, it could make a small, but important, contribution to improving the image of the state’s food products.