The Agriculture Implications of the North American Free Trade Agreement

December 16, 1993

PAER-1993-18

Marshall A. Martin, Professor

Background

After intense negotiations, Presidents Bush, Salinas and Mulroney from the United States, Mexico, and Canada, respectively, signed the North Ameri-can Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on December 17, 1992. On November 3, 1993 the Clinton Administration introduced into the U.S. Congress the NAFTA document plus several side agreements on labor and the environment. On November 17, 1993 the U.S. House of Representatives approved NAFTA (234 to 200). It was ratified by the U.S. Sen-ate on November 20, 1993 (61 to 38). The Canadian and Mexican parliaments also have ratified NAFTA.

NAFTA is scheduled to go into effect January 1, 1994. The Agreement calls for the eventual elimination of all tariffs, quotas, and licenses that act as trade barriers.

Some trade barriers will be eliminated immediately, while others would be reduced gradually over a period of up to 15 years. NAFTA is primarily a trade agreement and does not call for monetary nor political union as in the case of the Maastricht Treaty in the European Community.

Because of the way that Canada protects its agricultural sector, Canada was unwilling to liberalize agricultural trade with Mexico as much as was the United States. Hence, the primary focus of this article is on the expected agricultural trade impacts of NAFTA on the United States and Mexico. Some background on NAFTA is presented, the key agricultural trade provisions are outlined, and some of the economic implications of the agricultural pro-visions for the United States, and Indiana, are analyzed.

The Settling

For any analysis of the economic impacts of NAFTA it is important to keep the relative size of the two countries in proper perspective. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and population of the United States are

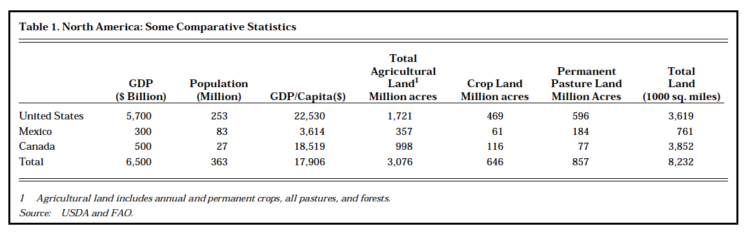

both quite large relative to Mexico. NAFTA will bring together a $6.5 trillion North American Trade Bloc ($5.7, $0.5, and $0.3 trillion in the United States, Canada, and Mexico, respectively) with a combined population of 363 million people (253, 27, and 83 million in the United States, Canada, and Mexico, respectively)(Table 1). Mexico’s population equals the combined population of the five most populous U.S. states (California, New York, Texas, Florida, and Pennsylvania) [U.S. Department of Commerce]. Per capita GDP in the United States is over six times that of Mexico ($22,530 compared to $3,614).

Agriculture is relatively more important in Mexico. U.S. agriculture accounts for about three per-cent of GDP compared to nine percent in Mexico. Two percent of the U.S. population is employed in agriculture compared to nearly one-third of the Mexican population.

U.S. agricultural exports and imports represent about 7 and 9 per-cent of GDP compared to 16 and 15 percent in Mexico.

Mexico is only one-fifth the size of the United States. Mexico’s total land area equals the combined area of Alaska and Texas, our two largest states. About two-thirds of the cli-mate in Mexico is arid or semi-arid, which limits agricultural production. Mexico’s cropland area is about 61 million acres compared to 469 mil-lion acres in the United States (Table 1). This translates into 0.7 acres per capita in Mexico compared to 1.9 acres per capita in the United States.

Irrigation is critical to crop pro-duction in many regions of Mexico. Since most irrigation water comes from surface storage rather than underground aquifers, available irrigation water is highly dependent on rainfall. Only 10 percent of U.S. arable land is irrigated compared to 20 percent in Mexico.

In 1992, total U.S. exports to Mexico were $40.6 billion. These exports are estimated to support about 700,000 jobs (Office of the U.S. Trade Representative). Mexico is the second largest market for U.S. manufactured exports.

Mexico is currently the third most important market for U.S. agricultural exports ($3.8 billion for fiscal year 1993), with Japan and Canada ranking first and second ($8.2 and $5.1 billion, respectively, for fiscal year 1993) [USDA, 1993]. Agricultural exports to Mexico in 1992 accounted for about 111,000 jobs. The U.S. agricultural trade balance with Mexico is currently positive ($3.8 billion exports versus $2.9 billion imports for fiscal 1993). Corn and soybeans normally account for at least one-third of total U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico. Other important exports are red meat, poultry, processed fruits and vegetables, dairy products, and limited amounts of wheat and rice.

After Canada ($4.4 billion in fiscal year 1993), Mexico is the next most important source for U.S. agricultural imports ($2.9 billion in fiscal 1993). Fruits and vegetables account for one-half of total U.S. agricultural imports from Mexico. Fresh winter vegetables are especially important. Tropical products such as coffee, bananas, and tea rep-resent slightly less than one-fifth of U.S. agricultural imports from Mexico. Mexico also exports feeder cattle to the United States.

After becoming a member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1986, Mexico has substantially liberalized its trade policies. Tariffs have been reduced sharply, especially for industrial goods. However, Mexico’s average tariffs are about 2.5 times higher than those for the United States (10 versus 4 percent) [Office of the U.S. Trade Representative]. Import licenses that formerly were required for nearly all agricultural imports have been retained for only a few products such as corn, poultry, grapes, and wood products. Although the licensing arrangements affect less than 6 percent of all Mexican tariff categories, these commodities represent about one-third of U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico.

The Basic Provisions of the Agreement

Under NAFTA, Mexico and the United States will eliminate all non-tariff barriers governing agricultural trade. Non-tariff barriers will be con-verted to “tariff-rate-quotas” (TRQs). Under TRQs, no tariff will be imposed on quantities below the quota amount. Imports above the quota limit will be subject to tariffs that will be gradually phased down over a transition period. Tariffs on a broad range of agricultural products will be eliminated immediately on about one-half of the bilateral trade between Mexico and the United States. Remaining tariff barriers will be phased out over a 10-year period. More sensitive commodities will have a 15-year transition period. Sensitive commodities include corn, dry beans, and nonfat dry milk for Mexico, and sugar, orange juice, and peanuts for the United States [USDA, 1992(a), 1992(b), 1992(c)].

Each country will move towards agricultural income and price sup-port policies that are not trade-distorting and that are in compliance with the final outcome of the current GATT negotiations. In general, export subsidies will be eliminated. Efforts will be made to harmonize agricultural product classification, grading, and marketing standards.

Table 1. North America: Some Comparative Statistics

U.S. agricultural imports from Mexico and Canada must meet all standards set by U.S. regulatory agencies. NAFTA contains an administrative procedure to resolve disputes over health and sanitary standards to avoid regulations disguised as trade barriers.

Rules of origin have been developed to prevent non-NAFTA countries from benefitting from the trade preferences in the Agreement. For example, milk from the European Community cannot be shipped to Mexico, processed into cheese or yogurt, and then shipped duty-free into the United States.

The NAFTA text calls for eco-nomic development in North America in an environmentally sound manner. Under NAFTA, the United States is allowed to maintain its own current stringent health, safety, and environmental standards. The Agreement prohibits the lowering of these standards to attract investment in Mexico. Both the United States and Mexico have committed resources to clean up the water and air in their common border area. Mexico has committed $460 million over three years and the United States has com-mitted $241 million for fiscal 1993, double the amount spent in 1992. For the long-term, NAFTA calls for cooperative programs covering pollution control, pesticides, waste management, and emergency responses.

The Agreement includes provisions on intellectual property rights. All three countries will be required to prevent infringements against patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets, both internally and at the border. This is especially import-ant for plant breeders and seed producers, agricultural chemical companies, and animal health product companies; and should facilitate technology transfer. Other general provisions include investment opportunities in agriculture, new international cargo markets for the trucking and railroad industries, and expanded trade in wood products.

A review of some of the provisions for the major agricultural commodities covered in NAFTA is informative. The tariff-rate-quota and transition period will differ for each commodity depending on its eco-nomic importance and sensitivity.

After 10 years, all U.S. livestock and products will be exported to Mexico duty-free. TRQs will apply during the 10-year transition period.

The current trade balance for fruits and vegetables is heavily in Mexico’s favor. To minimize any adverse economic impacts, 10- to 15-year TRQ safeguards will be used, depending on the sensitivity of the product. In general, the higher the current tariff, the longer the transition period.

Corn is the single most sensitive commodity for Mexico. Initially, a tariff-free import quota of 2.5 million tons will be established by Mexico. This is about twice the current annual volume of U.S. corn exports to Mexico. The duty-free quota will increase three percent per year over a 15-year period at which time corn will enter duty-free. Sorghum will enter duty-free immediately, while wheat and barley trade will be gradually liberalized.

Mexico is a good market for U.S. soybeans, about 13 percent of total U.S. soybean exports and 6 percent of soybean meal exports. The cur-rent 15 percent duty will be reduced to 10 percent, and then phased out over 10 years.

General Economic Implications

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has estimated that by 2008 when NAFTA is fully implemented U.S. agricultural exports would reach $10.1 billion, $2.6 billion more than without NAFTA. Also this increase in U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico would generate about 56,000 more U.S. jobs.

The desire for more rapid eco-nomic growth and job creation is a major force driving the Mexican government toward a trade agreement. In the first half of the 1980s, Mexico experienced rapid inflation, a recession, and a decline in per capita food consumption [Martin]. Since then, the Mexican government has shifted from a closed, inward-looking eco-nomic policy regime towards one that is more export oriented and open. Economic growth has accelerated from less than two percent per year in 1982-88 to 3.5 percent per year in 1989-91. Increased trade opportunities under NAFTA are expected to result in continued rapid economic growth into the next century.

Continued strong per capita income growth, coupled with a population in excess of 83 million people that is growing about two percent per year, will result in rapid growth in Mexican food demand in the 1990s. This will be especially true for foods such as livestock products for which demand growth is closely associated with increases in per capita income growth. The demand for livestock products could increase about 3.0 to 3.5 percent per year. And, if Mexico wishes to help people increase their per capita consumption of livestock products at lower real prices, livestock supplies will need to increase even faster. Mexico will need to import from the United States both feed grains and oilseeds to produce more livestock in Mexico, import live animals for slaughter, and import processed meats and dairy products [Martin].

A second implication of economic growth in Mexico will be to stimulate the Mexican demand for fruits and vegetables. Hence, Mexico is expected to devote an increasing amount of land, labor, fertilizer, credit, and scarce irrigation water to the production of fruits and vegetables. This will create jobs, especially for people with limited skill levels, and also will increase rural wages and help reduce immigration into the United States.

The implementation of NAFTA will stimulate Mexican production and export of fresh and processed fruits and vegetables. Mexican exports to the United States of fresh winter vegetables such as tomatoes, bell peppers, and cucumbers as well as exports of fresh fruits such as strawberries and mangos are expected to increase. Mexican exports to the United States of processed vegetables such as frozen broccoli and cauliflower will likely increase also.

Economic Implications for Major Commodities

NAFTA has important economic implications for several major agricultural commodities. A few key implications are outlined below [USDA, 1992(a), 1992(b), 1992(c); U.S. Congress].

Livestock and Products

Under NAFTA, bilateral beef trade will likely increase. In 1991, the United States exported about 64,000 tons of beef and 140,000 head of slaughter cattle to Mexico. The United States also imported around one million head of feeder cattle from Mexico. The United States would have imported more feeder cattle if Mexico had not imposed an export tax of about $60 per head. USDA estimates suggest that under NAFTA by the year 2008 when it is fully implemented annual U.S. beef exports could grow to about 200,000 tons plus one million head for slaughter in Mexico. Also more feeder cattle will likely leave Mexico for U.S. feedyards. Lack of concentrate feed and limited water and pasture land will encourage Mexico to export more feeder cattle. However, this may be offset by rising per capita incomes in Mexico that will increase the demand for beef. Live cattle prices in the United States might increase by one percent as a result of NAFTA.

U.S. pork exports to Mexico are expected to double by the end of the 10-year transition period, but remain small as a percent of U.S. swine production. Elimination of Mexican import tariffs and per capita income growth in Mexico will contribute to the growth in U.S. pork exports to Mexico. Import tariffs on slaughter animals and pork products are now about 20 percent, and will be eliminated over a 10-year transition period. The United States will not import live hogs or fresh or frozen pork from Mexico because of dis-ease problems, mainly hog cholera which has been eradicated in the United States. Market hog prices in the United States might be about

$1.00 per hundredweight higher under NAFTA.

Mexico is the number one importer of powdered milk from the United States. Mexican tariffs (up to 20 percent) are the major barrier to U.S. dairy exports to Mexico. Depending on the specific dairy product, under NAFTA all tariffs will be reduced over a 10- to 15-year period. Dairy imports by the United States are subject to Section 22 of the U.S. Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 which severely restricts the quantity of dairy products imported in order to maintain U.S. dairy price supports. The United States will increase the duty-free quantities of dairy imports from Mexico by three percent per year over a 10-year period at which time U.S. tariffs will be eliminated.

Under NAFTA, income growth and the removal of import licenses will expand the Mexican market for eggs. Over the 10-year transition period, U.S. egg exports to Mexico are expected to increase 4- or 5-fold.

Fruits and Vegetables

While currently ranging from 0 to 30 percent, U.S. import tariffs on vegetables, many applied seasonally, will gradually be eliminated under NAFTA. The United States currently imports about $1 billion of vegetables and melons from Mexico annually. Fruit and vegetable imports are expected to increase gradually over the phase-in period.

The United States will have greater access under NAFTA to the Mexican market for temperate climate fruits such as peaches, apples, and pears. Mexico will have greater access to the U.S. market for strawberries and grapes.

The United States and Mexico currently engage in two-way trade in oranges. With the elimination of trade barriers, U.S. exports to Mexico of fresh oranges are expected to increase. Mexico is likely to increase its exports of orange juice concentrate to the United States. Overall, NAFTA’s impact on U.S./Mexican citrus trade will be small, perhaps a 3-4 percent increase over the transition period.

Grains

The United States supplies most of Mexico’s corn and sorghum imports. As tariffs on corn are eliminated over the 15-year transition period, USDA estimates that the volume of Mexican imports of corn from the United States, mainly to satisfy an expanding livestock sector, will increase about 50 percent. While the United States is a major wheat supplier to Mexico, these exports represent only about two percent of total U.S. wheat exports. With the elimination of tariffs, U.S. wheat exports to Mexico are expected to increase about 40 percent.

Oilseeds

NAFTA is expected to have only a modest impact on the U.S. soybean industry. Mexico prefers to import soybeans for crushing since it needs both cooking oil and meal for live stock. Exports of U.S. soybeans to Mexico are estimated to increase about 20 percent under NAFTA.

Implications for Indiana

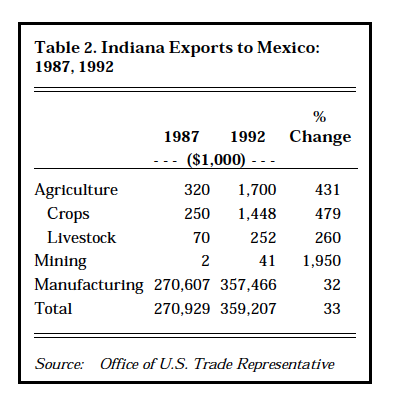

In 1992, Indiana exports to Mexico were $359 million, up 33 percent since 1987—the first year after Mexico joined the GATT and began to reduce major trade barriers (Table 2). Agricultural exports to Mexico from Indiana were $1.7 million with about 85 percent of this being grain and oilseed crops. Food product exports from Indiana to Mexico last year totaled $4.9 million. While crop, livestock, and processed food exports from Indiana to Mexico are a small fraction of the State’s total exports to Mexico their significance has increased over the past 5 years.

Table 2. Indiana Exports to Mexico: 1987, 1992

It has been estimated that under the full implementation of NAFTA by 2008, Indiana’s agricultural receipts will increase $100 million per year or about 2.2 percent

[Paarlberg]. Most of this increase will be from the higher price and export sales of corn and soybeans. In addition, increased exports of live-stock and livestock products is expected, especially pork and poul-try. It also has been estimated that 2,629 agriculturally related jobs will be generated in Indiana [Broomhall].

Conclusions

NAFTA is expected to increase employment and income in Mexico, Canada, and the United States. While the agricultural provisions will have some modest negative eco-nomic impacts, overall Mexican and U.S. agriculture is expected to gain economically from the Agreement. Some jobs and income may be lost in the U.S. winter vegetable region, but Mexico will gain from increased vegetable production and exports to the United States and Canada. U.S., and Indiana, oilseed and grain producers, as well as livestock producers, will benefit from increased exports to Mexico as growth in per capita income expands the Mexican demand for livestock products.

The Agreement addresses several controversial issues related to agricultural trade such as intellectual property rights, environmental quality, and food safety. The Clinton Administration has drafted legislation to clarify some of these concerns.

From an agricultural perspective, NAFTA will be beneficial to consumers and most farmers in all three countries. However, economic adjustments will be difficult for some less technically advanced farmers in Mexico and for U.S. winter vegetable growers.

* This article draws heavily from Mar-shall A. Martin, The North American Free Trade Agreement: Implications for Agricultural Trade, Atlantic Economic Society Best Papers Proceedings, 3(2):133-138. July 1993.

References

Broomhall, David E. Impacts of NAFTA on Income and Employment in Indiana, unpublished manuscript, Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University, November 1993, 1 pp.

Food and Agriculture Organization, FAO Production Yearbook, United Nations, Rome, 1987.

Martin, Marshall A. United States-Mexico Agricultural Trade Relations, Unpublished manuscript prepared for the U.S. Council of the Mexico-U.S. Business Committee, 1990, 35 pp.

Office of U.S. Trade Representative, The NAFTA: Expanding U.S. Exports, Jobs, and Growth, Washington, D.C., July 1993, 11 pp.

Paarlberg, Philip L., Impacts of NAFTA on Indiana Agriculture, unpublished manuscript, Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University, November 1993, 2 pp.

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, U.S.-Mexico Trade: Pulling Together or Pulling Apart?, ITE-545, Washington D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, October 1992, 225 pp.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture in a North American Free Trade Agreement: An Analysis of Liberalizing Trade Between the United States and Mexico, Foreign Agri-cultural Economic Report 246, Economic Research Service, Washington D.C., September 1992(a), 167 pp.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Preliminary Analysis of the Effects of the North Ameri-can Free Trade Agreement on U.S. Agricultural Commodities, Office of Economics, Washington D.C., September 1992(b), 26 pp.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, “U.S.-Mexico Agricultural Trade Under a NAFTA”, Agricultural Outlook, AO-186, June 1992(c), pp. 32-37.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Outlook for U.S. Agricultural Exports, Washington, D.C., August 27, 1993, 22 pp.

U.S. Department of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 112th edition, 1992.