The U.S. Economy, 2000: A New Track Record

March 13, 2000

PAER-2000-03

Larry DeBoer, Professor

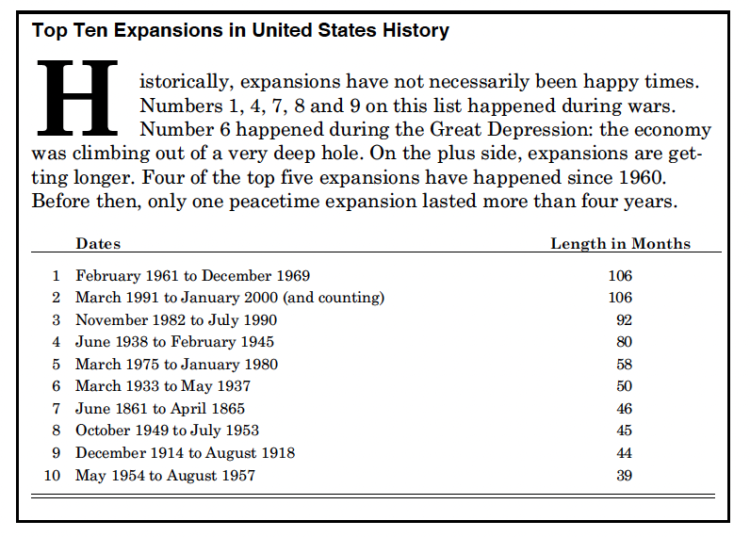

Maybe I’m too picky, but we still don’t know for sure that this is the longest economic expansion in United States history. Many newspapers proclaimed that the record had been reached on February 1, 2000. True, February is the 107th month since the expansion began in March 1991, and the old record from the 1960s is 106 months. But what if a recession started in February? Then this expansion only ties the record. To avoid counting chickens, let’s post-pone the celebration until all the February data is in. By the end of March we’ll know whether we’re in record territory.*

The good news went on and on in 1999. Gross Domestic Product grew 4.0% above inflation, almost 6.0%over the second half of the year. The unemployment rate dropped to a 30 year low at 4.0%. Inflation increased to 2.7%, higher than in 1996 or 1997, but that was due to the oil price hikes. Take out energy prices and the inflation rate was lower in 1999 than in any year in the ‘90s. Interest rates increased, with the strong demand for investment funds, and rate hikes by the Federal Reserve.

Just how long can these good times roll? It’s possible that this expansion can last for some time to come. The reason is low inflation.

Why No Inflation?

Inflation tends to increase when unemployment is low. The reasoning is pretty simple (maybe too simple). If workers are scarce, companies that want to expand must raise wages to fill new job openings. Higher wages attract employees from other companies, and from other pursuits like homemaking, attending school and the armed forces. To cover these higher wages, companies raise their prices. The scarcity of workers leads to faster price increases—inflation.

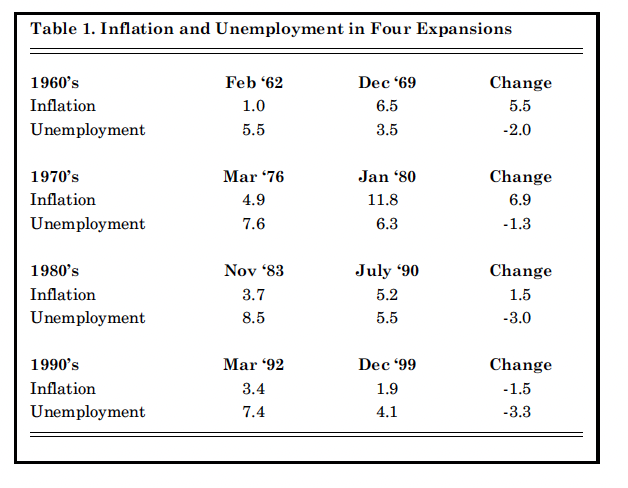

Not in this expansion, though. Inflation is still low after almost nine years. To see how weird this is, com-pare this expansion to the other long expansions since 1960. Table 1 shows the inflation rate over the first 12 months of the expansion, and over the last 12 months of the expansion, and the unemployment rate in the last month of those periods. Inflation is measured with energy prices excluded, because energy prices reflect Middle East politics as much as the scarcity of workers.

The table shows that in the 1960s, unemployment fell and inflation increased. In the 1970s, unemployment fell and inflation increased. In the 1980s, unemployment fell and inflation increased. In the 1990s, unemployment fell and inflation fell too. The “rule of thumb” based on the experience of previous years was that unemployment rates under 6%produced rising inflation. But unemployment has been under 6% since September 1994, and inflation is a full percentage point lower now than it was then. Economics is like that. Just when you think you know some-thing, you don’t.

What’s going on? Probably, some combination of more rapid productivity increases and increased international competition. Productivity measures the amount of goods and services produced per person or machine. Productivity tends to increase when people have more and better equipment with which to work (and when machines get to work with more highly skilled people). Computers and new information technologies are the kinds of new and better machines that are probably raising productivity. With productivity increases, when labor is scarce and wages are bid upward, companies can cover higher pay with revenue from more production, not higher prices. Rising productivity tends to keep inflation down.

Competition is increasing, especially international competition for lower technology, wage-intensive goods. The share of imports in Gross Domestic Product rose from 4% in 1960, to 11% in 1990, to 14% in 1999. Companies do not feel confident enough of their customers and markets to try to pass on cost increases in higher prices. Some other firm, domestic or international, may hold the line on prices and steal the company’s customers. With business information increasingly available over the internet, customers are sure to find out about the competition’s lower prices, too.

Inflation and Recessions

Table 1. Inflation and Unemployment in Four Expansions

Inflation increased during every previous expansion, and, of course, every expansion was followed by a recession. Is there a connection between rising inflation and the onset of recession? There may be, through interest rates and the Federal Reserve. The “Fed’s” main job is to keep inflation under control. Its main tool is interest rates. When inflation rises, the Fed raises inter-est rates. This cuts borrowing, so it cuts housing construction, business investment, and consumer purchases of high priced goods. Higher interest rates may slow the stock market, which also could cut consumption and investment. Higher interest rates could raise the value of the dol-lar, which cuts exports and increases imports. With consumption, investment and exports down, and imports up, unemployment rises, and workers and firms find they must accept smaller pay hikes and price increases. Inflation falls.

Unfortunately, it takes many months for higher interest rates to slow the economy. And the link between the size of an interest rate hike and the amount the economy slows is uncertain. The Fed must guess future inflation from current conditions, in order to raise interest rates before inflation starts. Under these conditions, the Fed could make a mistake, raise rates too much, and slow the economy all the way into recession. If there is no inflation, the Fed need not raise interest rates sig-nificantly, so the danger of an acci-dental recession is less.

Sometimes a recession is no accident. From 1979 to 1982, inflation got so bad that the Fed deliberately increased interest rates so much that the economy fell into recession. If inflation is high enough, a recession may be the only solution. If there is no inflation, a recession is not needed.

The Fed’s main goal is low inflation, but usually it’s concerned about unemployment as well. Again, interest rates are its main tool. Lower interest rates encourage more consumption, investment and exports, which increase job opportunities and reduce unemployment. A problem is what to do when inflation is high and unemployment is rising. Should the Fed fight inflation with higher interest rates, or fight unemployment with lower interest rates? High inflation inhibits recession-fighting interest rate cuts. When there is no inflation, the Fed can feel free to cut interest rates at the first sign of trouble. That’s what happened in Fall, 1998, when the Asian crisis seemed about to affect the U.S. The Fed cut interest rates and averted a crisis. Had inflation been high, perhaps they would have thought twice about interest rate cuts.

Paragraph 1. Top Ten Expansions in United States History

The Fed isn’t the only economic policy player. Congress and the President can influence the course of unemployment and inflation through fiscal policy—changes in taxes and spending. For almost twenty years this policy avenue was blocked by large Federal budget deficits. In a recession, deficits inhibit tax cuts or spending hikes. But now, the Federal government’s budget surplus is so large that fiscal policy could be used without much restraint. Taxes could be cut and government spending increased, in order to reduce unemployment.

All this means that with inflation low, the Fed has no need to create an inflation-fighting recession, is less likely to engineer an accidental recession, and can freely use its interest rate tool to fight a recession that threatens the economy anyway. With the surplus large, Congress and the President could respond to recession with tax cuts and spending hikes. Recession is less likely when inflation is low and the surplus is large.

It’s a New Millennium, But. . .

Falling inflation, rapid productivity growth, and growing global trade have created a lot of excitement in business and economic circles. In its January 1, 2000 issue, a Wall Street Journal headline read “So long, Sup-ply and Demand. There’s a new economy out there—and it looks nothing like the old one.” **

It’s a new millennium, but some things probably won’t change. Probably, prices will still rise and fall with changes in demand and supply. Probably, recessions still will hap-pen. With inflation so low, there probably won’t be a recession accidentally created by the Fed’s relatively small interest rate hikes. But recessions can be caused by other shocks to the economy, too. Here are a few possibilities:

- Suppose the stock market crashes. It’s happened before, sometimes with nasty consequences, as in 1929, sometimes without troubling the rest of the economy, as in 1987. Consumers and companies could respond to a crash with lower spending. Jobs would disappear, unemployment would rise, output would fall.

- Suppose there’s a run on the dollar by international investors. It happened to Asia’s currencies in 1997-98, and it even happened to the U.S. in the 1890s. Perhaps it could happen to our economy today, especially because we’ve been borrowing so much to finance our large trade deficit. Funds would be pulled out of the U.S. The Fed might raise interest rates to support the value of the dollar. Spending would fall, unemployment would rise, output would fall.

- Suppose oil prices rise even more, raising the price of gasoline to, say, double what it was at the beginning of the year. Prices doubled like that twice in the 1970s, and twice contributed to recessions. Companies facing higher costs would reduce production, lay off employees and try to pass higher costs along in higher prices. The Fed might fight these higher prices with higher interest rates. Spending would fall, unemployment would rise, output would fall.

- None of these three seem very likely, though the oil price scenario seems more believable now than it did last year. But they’re not called “shocks” for nothing. Events such as these are unpredictable. Still, with inflation so low, the Fed is in a better position to do something about them. And with the budget surplus so large, Congress and the President can use fiscal policy to help.

- Suppose oil prices rise even more, raising the price of gasoline to, say, double what it was at the beginning of the year. Prices doubled like that twice in the 1970s, and twice contributed to recessions. Companies facing higher costs would reduce production, lay off employees and try to pass higher costs along in higher prices. The Fed might fight these higher prices with higher interest rates. Spending would fall, unemployment would rise, output would fall.

None of these three seem very likely, though the oil price scenario seems more believable now than it did last year. But they’re not called “shocks” for nothing. Events such as these are unpredictable. Still, with inflation so low, the Fed is in a better position to do something about them. And with the budget surplus so large, Congress and the President can use fiscal policy to help.

The Outlook for 2000

Alan Greenspan, perhaps the first celebrity economic policy maker, will head up the Federal Reserve for four more years. The economy is at full capacity, with very low unemployment rates, yet it continues to expand at rates above even optimistic estimates of sustainable growth. If it grows fast enough even higher productivity growth won’t stop inflation from rising. The Fed has already increased interest rates this year, and will probably do so again, to try to get 4 to 6% growth down to the 3%to 3.5% range. With these rate increases, and the strong demand for funds by businesses and consumers, expect the short term Treasury rate to rise to 5.6%, and the long term Treasury rate to 6.8%, by this time next year.

There appears to be no recession in the near future. Growth might slow in 2000, if higher interest rates bite, but this may be what is needed to be sure that inflation remains under control. Expect GDP to grow 3.5% above inflation over the next year.

With productivity growing as much as it is, GDP growth of 3.5%per year should not affect the unemployment rate much. Large numbers of new employees won’t be needed to produce this extra output if each employee is producing so much more. This means the unemployment rate should remain around 4.2% by the end of 2000, near where it is now. Inflation has been increasing due to oil price hikes, but there is as yet no sign of an upward trend in underlying inflation. Recent rapid growth seems likely to put some upward pressure on prices, but if growth slows to 3.5%, the increase in under-lying inflation (not counting energy) should be small. Expect the inflation rate to be 2.4% over the coming year.

Paragraph 2. Follow the Economy on the Web

If all this comes true, in March 2001 we’ll mark another record: a ten-year expansion.

* To be “really” picky, it will take even longer to know. A rise in inflation-adjusted GDP is the true measure of expansion, and the final GDP figures for the first quarter won’t be out until June 29.

** The next week, another newspaper available in supermarkets, the “Weekly World News,” ran this headline: “Panic!Second Great Depression by March!” At least we’ll set the record.