Threats to Local Government Revenues from the Coronavirus Recession

April 13, 2020

PAER-2020-06

Author: Larry DoBoer, Professor of Agricultural Economics

The coronavirus recession is upon us. Unemployment is rising to double-digits, incomes are falling, and spending on non-essential products has dropped. Many people are sick; many more people face hardships.

Local governments will face hardships too. Counties, townships, cities and towns, school districts, library districts and special districts receive revenue from property taxes, many receive revenue from local income taxes, and school districts receive a large amount of revenue from state aid. All of these revenue sources are threatened by the recession, but how they are threatened depends on the characteristics of each revenue source.

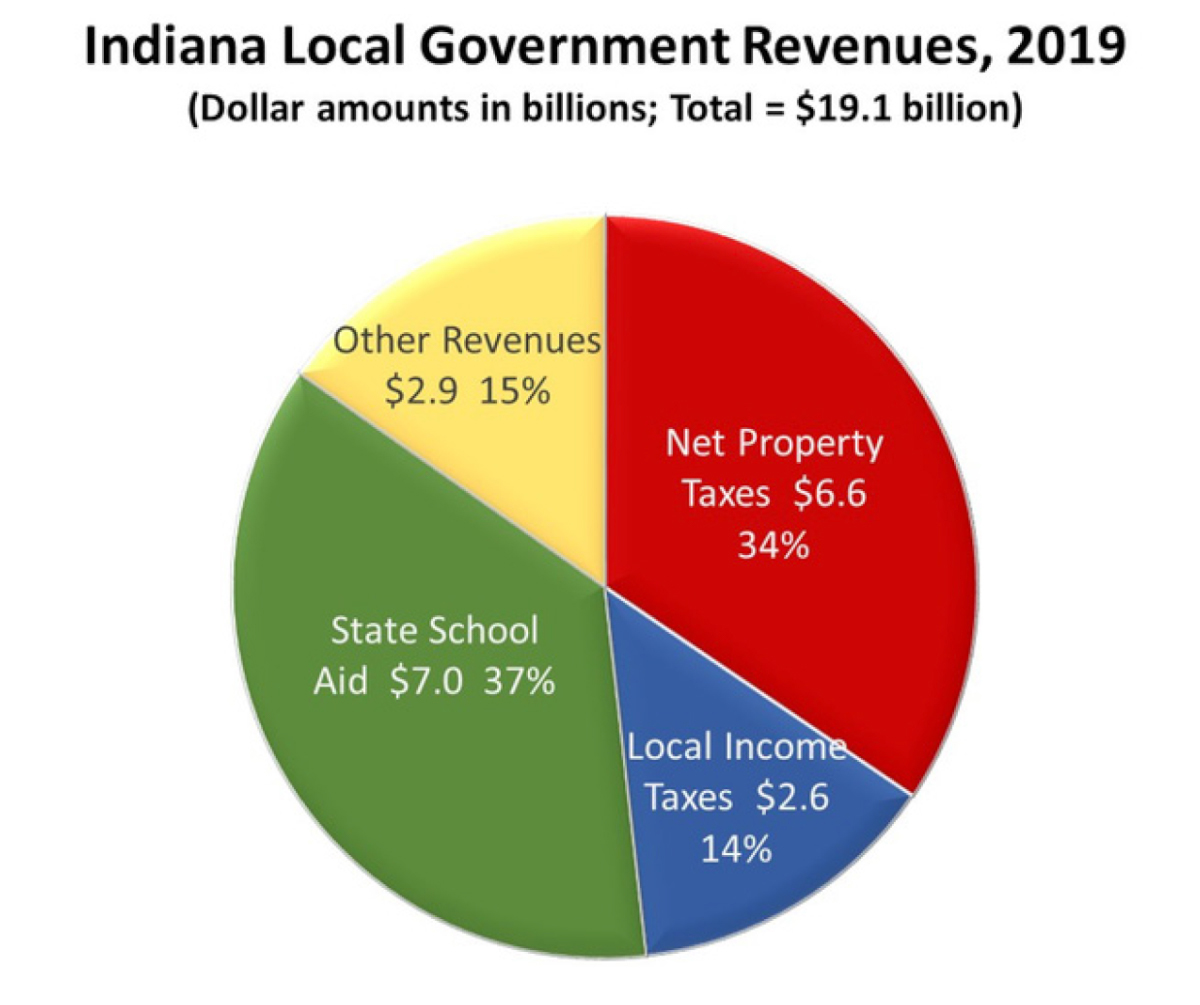

Property taxes, local income taxes and state school aid make up 85% of total local revenues (Figure 1). The recession could affect all three in the short run, and over longer periods of time.

Property Taxes

Property taxes are based on the assessed value of property, less deductions. Tax bills this year are based on assessments in 2019, which were set based on property values in 2018. Local governments set their levies each year based on their budget needs and on a state-imposed maximum levy. The levy is divided by taxable assessed value to set the tax rate, measured in dollars per $100 assessed value. That rate times the assessment of each taxpayers’ property is the tax bill, subject to the Constitutional tax caps. Bills that exceed the caps receive a credit, which is money taxpayers do not pay, and revenue local governments do not receive.

Taxpayers pay their property tax bills in two installments, in May and November. The County Treasurer collects the revenue, which is distributed to local governments in June and December. Taxpayers who are late with their payments pay a penalty.

The tax rates are already set and tax bills are based on last years’ assessments. It would appear that property tax revenues in 2020 cannot be affected by the current recession.

However, on March 20 Governor Holcomb responded to the hardships imposed by the recession and announced that the penalties for late-payment of property taxes would be delayed for 60 days. While the deadline remains May 11, there is no penalty for late payment until July 10. It’s possible that property owners who have seen their incomes fall will pay late. It’s possible that taxpayers who have not lost income will pay late too, taking advantage of the delay to earn a little interest on their money. And, some tax payments will become delinquent, as taxpayers find they cannot meet their tax obligations out of their reduced incomes.

It’s likely that the June distribution of property tax revenues to local governments will fall short of expectations. This may require tapping balances or borrowing temporarily from public or private lenders. Local governments also may request advances on the December distribution from the County Treasurer. The Department of Local Government Finance published documents to assist local governments in solving any cash flow problems.

Will the coronavirus recession cause people to delay or cancel home building? Will businesses delay or cancel construction of buildings or purchases of equipment? Will the recession last long enough to depress property values? During the Great Recession, in 2007-09 and after, construction activity was reduced and property values did fall.

The assessment system responded to these changes. Total gross assessed value before deductions decreased after the Great Recession. Statewide assessments peaked in tax year 2010 at $458 billion, then fell 1.5% in 2011. Assessments did not regain their 2010 peak until 2015.

The quantity and value of property in 2020 will be assessed in 2021. Those assessments will be the basis for tax rates and tax bills in 2022. Lower assessments could mean lower tax levies, but more likely local governments will set their levies at the state-imposed maximum. Tax rates required to raise those levies will be higher if assessments are lower. Higher tax rates will push more taxpayers above their Constitutional tax caps, which will increase tax cap credits and reduce the share of the levy that local governments can collect. Local governments that overlap cities or towns are particularly vulnerable to these revenue losses.

Property tax levy growth could be restricted well into the 2020’s. Yearly increases in the maximum levies are governed by the Maximum Levy Growth Quotient. The MLGQ is the percentage that the state-imposed maximum levy can rise each year. It’s based on the annual percentage increase in Indiana non-farm personal income, averaged over six years. The MLGQ is announced by the state each summer in advance of the local budget process. This year the MLGQ is based on annual income growth from 2013 to 2018, which averaged 3.5%. Next year the MLGQ will be about 4%, based on numbers from 2014 to 2019.

The maximum levy growth quotient makes sure that property tax levies do not rise faster than taxpayers’ abilities to pay, as measured by income. It’s a tax break for taxpayers, but a limit on revenues for local governments.

The U.S. Department of Commerce will tabulate personal income for 2020 by the summer of 2021. It will first enter the MLGQ six-year average in 2022. It’s likely that Indiana income in 2020 will decline, which means that a negative number will enter the average in 2022, and remain in the MLGQ calculation for six years, through 2027. Maximum levies will grow more slowly as a result.

This happened after the Great Recession. In 2009 Indiana non-farm personal income dropped by 2.4%. This figure entered the MLGQ in 2011 and remained until 2016. During that time the average growth quotient was 3.3%. In 2010 it had been 3.9%; in 2017 it was 4.2%.

Local Income Taxes

All Indiana counties have adopted local income taxes. The LIT revenue is distributed to county, city and town governments, and in some cases to all other local governments. LIT payments are collected by the state along with the state income tax and distributed to counties each month. The distributions are set in advance. Distributions for 2020 were certified by the State Budget Agency in August and September of 2019. These distributions were based on revenue collections in each county during the previous state fiscal year, July 1, 2018 through June 30, 2019. This means that LIT distributions in 2020 cannot be affected by the current recession.

It’s tempting to say the same thing about LIT distributions in 2021, since they will be based on collections this year, which reflect taxes on incomes earned last year. However, the Federal government postponed the due date for income tax payments from April 15 to July 15, and the Governor followed suit for Indiana’s state and local income taxes. LIT distributions for 2021 will be calculated based on revenue collections through June 30, and the deadline for paying taxes is now after that date. If many people delay their income tax payments, collections by June 30 will be lower, and so distributions will be lower in 2021. It may be possible to extend the collection deadline, but if not, the revenue will be part of the 2022 distribution.

Distributions in 2022 will be based on tax collections through June 2021. Those tax payments will be based on incomes earned this year. A recession this year will affect local government LIT revenues in 2022.

It’s possible that LIT revenues will be affected beyond that. Distributions are set in advance. Revenue collections come later. After the last two recessions in many counties distributions exceeded collections, and the balances in county accounts became negative. The state had to restrict distributions below collections in later years, until balances were back in the black.

In Elkhart County, for example, balances became negative in early 2009, and were in the red by $19 million in 2011. Distributions were limited below collections through 2013 to rebuild balances. The recession that hit the Elkhart economy in 2008 was still limiting LIT revenues in 2013.

After the Great Recession the General Assembly created a new system for setting distributions and account balances. Distributions were set based on previous collections. The minimum balance in each county’s account was set at 15% of distributions. When balances exceeded 15% the state makes a supplemental distribution, so that local governments can use this tax revenue to pay for services.

The 15% minimum balance was set based on an analysis of Elkhart County during the Great Recession. Elkhart was chosen because it is the most volatile economy in Indiana. If 15% is enough to keep Elkhart in the black, it should do the same for all counties. The analysis was based on collections and distributions during the Great Recession, because it was the worst recession since the Great Depression.

At the time it was hard to imagine a recession deeper than the Great Recession—the unemployment rate in Elkhart reached Depression-levels at 20%. Unfortunately, it’s possible that this recession will be even worse. If so, balances may again go negative, and LIT distributions would have to be limited into the decade of the 2020’s.

State School Aid

State tuition support for school districts is distributed by formula. The formula is set during state budget years, and the total amount to be distributed is appropriated based on forecasts for revenue for the two-year biennium. The appropriations are in the budget bill, so a recession should not affect distributions to school districts through the end of the biennium in June 2021. Tuition support for local schools is $7 billion, more than 40% of the 2020 general fund budget.

However, state revenues will be hard hit by the recession. Most general fund revenues come from sales and income taxes, and the recession and stay-at-home orders will reduce spending and earnings. In March revenues fell short of forecast by 6%–and that mostly reflected economic activity from February. Bigger shortfalls are expected for the remainder of this fiscal year, and into the next.

During the Great Recession in fiscal 2009 revenues fell short of forecast by $1.4 billion, which was 10% of the budget at the time. State balances dropped to $830 million at the end of fiscal 2010, 6.7% of the general fund budget. This was close to the accepted 5% minimum required for cash flow purposes.

A similar shortfall now would amount to $1.7 billion. Indiana’s budget balance at the start of the 2020 fiscal year was $2.3 billion. The 5% minimum is $850 million. So, the state has about $1.45 billion to use to cover a shortfall. If the revenue drops 10% below forecast, those balances could cover appropriations for about 10 months.

Great Recession revenue shortfalls lasted for several years, however. Governor Daniels was forced to reduce spending below appropriations. Money not spent “reverts” to the general fund, and reversions increased from an average of $130 million per year in the 5 years before the recession, to an average of $650 million per year in fiscal years 2009-2011. Because school aid was such a large share of the budget, it had to be cut. That may be necessary again, depending on the depth and length of the coronavirus recession.

State aid is distributed on a per-pupil basis. The count of students is taken early in the fall semester. Will parents send their children back to school in August? If the virus is not yet under control, more parents than usual may decide to home school their children. Pupil counts would drop, and so would state aid. The undistributed aid would revert to the state general fund.

Next year, 2021, is a budget year in the General Assembly. The legislature will set state appropriations for fiscal years 2022 and 2023. Appropriations will be based on revenue forecasts, which will be released in December 2020 and revised in April 2021. If the recovery from this recession is slow, forecast revenue growth will be low, growth of appropriations will be limited, and state aid to schools will grow slowly, if at all.

A wild card in the budget is Federal aid. During the Great Recession the Federal government provided Indiana with $2.2 billion in added revenue. The Federal share of Medicaid payments was increased, which saved the state $1.4 billion, and there was $800 million more in fiscal stabilization money. The Federal CARES act included revenue to meet added coronavirus spending, but how much of this can replace lost state revenue remains to be seen.

Other Revenues

Property taxes, local income taxes and state school

aid are the three biggest sources of revenue for local governments. Other revenues are much smaller individually, but amount to 15% of the total. Many also are vulnerable to recession.

State road aid comes from current motor fuel tax receipts, and is distributed to counties, cities and towns by formula. This money is used to support road maintenance and construction. Fuel sales are down, and soon road aid will fall too.

Motor vehicle excise taxes are paid on the vehicles owned by Indiana residents. New vehicles are taxed at higher rates. Revenue growth will slow as new vehicle sales fall. Excise surtax and wheel tax revenues will fall as well.

Counties collect innkeeper’s taxes on hotels and motels. A few local governments receive revenue from added sales taxes on restaurants. Collections from these revenue sources will drop substantially. Also, likely to drop are parking fees, mass transit fares, recreational fees, and even speeding ticket fines.

Conclusion

The three biggest sources of revenue for Indiana local governments are property taxes, local income taxes and state school aid. This year, revenues from all three ought to be immune from the coronavirus recession. Property tax assessments, tax rates and levies are already set for 2020. So are local income tax distributions and state appropriations for school aid. There are short run dangers from property tax payment delays and school enrollment declines and emergency cuts in school aid if state revenues fall far short.

This year’s recession is more likely to affect local governments in 2021 and after. Property assessments could fall, increasing tax rates and tax cap credit revenue losses. Limits on property tax levy growth may get tighter, and last through most of the coming decade. Income losses will affect local income tax distributions in 2022. A really severe recession could deplete local income tax balances. Diminished state revenue forecasts could cut school aid growth in the next biennium.

State and local governments must balance their budgets. Revenue losses, now or in the future, can only mean budget cuts and, probably, reductions in service delivery.

Sources

Department of Local Government Finance. COVID-19 Actions. Executive Order on the Waiver of Penalties for Delinquent Property Tax Payments. March 20, 2020. https://www.in.gov/dlgf/9707.htm

Department of Local Government Finance. COVID-19 Actions. Supplemental Memo on Executive Order #20-005 – Cash Flow Solutions. March 30, 2020. https://www.in.gov/dlgf/9707.htm

Indiana Department of Education. Office of School Finance. Indiana K-12 State Tuition Support Annual Report. December 2019. https://www.doe.in.gov/finance

“Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb Gives Coronavirus Update,” March 26, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZcnAK3qoDHM

Indiana State Budget Agency. FY2020 Monthly Revenue Reports. March 2020 Monthly Revenue Report. April 10, 2020. https://www.in.gov/sba/2788.htm

Indiana State Budget Agency. Local Income Tax Distributions to Counties. 2020 Certification Calculations. November 18, 2019. https://www.in.gov/sba/2587.htm