Trade Prospects for Eastern Europe and U.S. Farm Commodities

March 16, 1990

PAER-1990-1

Author: Philip L. Paarlberg, Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics

With dramatic political and economic events occurring almost daily in Eastern Europe, U.S. farmers wonder if this promises a huge new growth market for farm products. Is such optimism warranted, or will they be disappointed? This article examines the likely impact of recent developments in Eastern Europe on U.S. agricultural trade. First, the article describes the current situation in Eastern Europe and reviews how that situation developed. Next, future prospects are considered.

The future of Eastern Europe is very uncertain. At a recent conference of agricultural trade researchers, it was noted that historically we referred to these nations as centrally planned. However, an economist from Poland rose and suggested that we now refer to the Eastern Bloc countries as the unplanned economies. That is a good description of Eastern European economies, for forecasts of where these nations are headed are guesses or perhaps hopes.

The Current Situation

While conditions vary from one nation to another, in general, per capita food consumption and imports have stagnated or fallen while foreign debt has swelled. Shortages of goods are chronic. One former student at Purdue University, now in West Germany, reports that East Germans are using the “welcome money” given them by the West German government to buy fruits, chocolate, and small appliances. These items disappear as quickly as stores along the border with East Germany can place them on the shelf. There are reports that the food aid sent to Poland by the West sits on the docks because the transport system has failed to operate. When the Polish government released prices on January 1, 1990, the price of food rose 400 percent and the price of fuel went up 600 percent. With incomes by western standards, such price increases quickly erode purchasing power.

Even before 1989, the economic situation of these nations was poor. Inflation was a major problem. In 1988, inflation reached 18 percent in Hungary, 61 percent in Poland, and more than 200 percent in Yugoslavia. Economic growth during the 1980s was slow. Only Bulgaria and Poland showed increased economic growth in 1988. Yugoslavia reported a real decline of 2 percent, while other nations’ economic growth slowed.

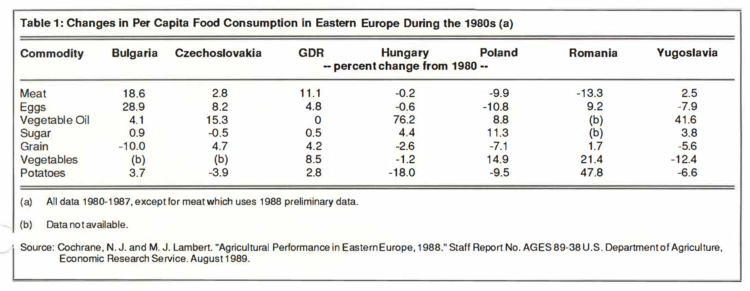

The 1980s have not been kind to Eastern European consumers (Table 1). Per capita consumption for several commodities has fallen, especially in Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia. In several other cases, the growth in per capita consumption has been very modest. For meat, only Bulgaria and East Germany (GDR) report large increases, while the other nations show either a slow rise or a decrease. Romania, for example, reports a 13 percent decrease in meat consumption through 1988 but substantial increases in use of vegetables and potatoes. Per capita uses of eggs, grain, and potatoes are falling in Hungary, Poland, and Yugoslavia. Of the commodities listed in Table 1, only per capita use of vegetable oils and of sugar is consistently rising.

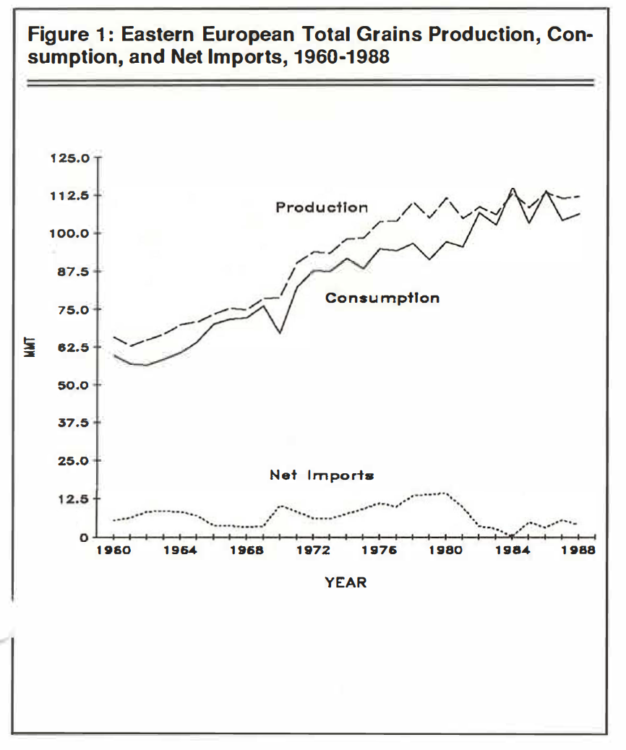

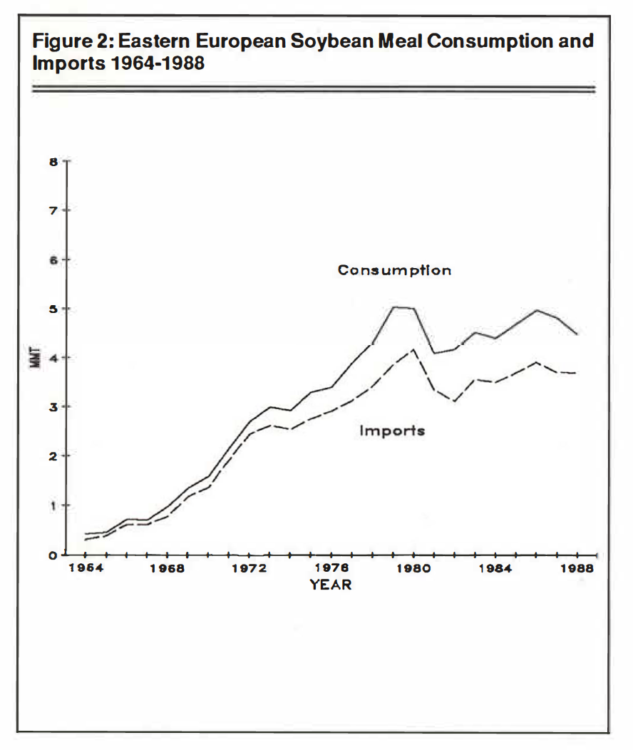

Except for Romania, all these nations have large foreign debts. Preliminary data for 1988 show gross external debt for the region as 112 billion dollars. This compares to 8 billion dollars in 1971 and 86 billion in 1981. Romania paid its foreign debt by forcing living standards lower to encourage exports. These external debts reduce income available for imports and increased consumption. Since 1980, net grain imports by Eastern Europe have fallen from 14 million tons annually to 3 to 5 million (Figure 1). In 1984, virtually no net grain imports were recorded. Soybean meal imports have not shown such a severe adjustment but rather stagnated in the 3-to-4-million-ton range (Figure 2). Stagnant meal imports and little domestic meal production limited growth in meal use. Whereas in the late 1970s annual use of soymeal was around 5 million tons, a decade later it still remained at that level. Despite the fall in net grain imports in the 1980s, grain consumption did not decline. In 1981 and 1983, grain use fell, but then recovered to levels slightly above those of the late 1970s. The increase use was the result of debt burdened nations encouraging internal production, which grew by 10 to 15 million tons from the late 1970s to late 1980s.

Background

Although events proceeded swiftly this past year, the decline of the Eastern European economies has been occurring for several years. In agriculture much of the problem lay with the centralized price structure. Agricultural prices were fixed at low levels and remained there for decades. Farm output growth was discouraged. As per capita incomes grew, consumption and imports rose. The increased food subsidies caused by consumer prices below world market levels swelled the governments’ deficits. Producer prices were adjusted upwards on occasion to encourage output, but without corresponding increases in consumer prices increased income continued to push food subsidies higher.

Attempts to raise consumer prices were strongly resisted by the population. In the early 1970s Polish food riots forced a change in the government. Food price increases also played a major role in the 1980s. The workers of Gdansk who formed the Solidarity union did not jump over the shipyard wall to protest political oppression. Rather they were opposing food price increases and the proposed closing of the shipyard. It is ironic that it is the Solidarity government which is now raising food prices.

Concern about the political sensitivity of consumer food price increases in 1970 led to a policy change with serious long-run implications that are only now becoming clear. Eastern European governments began large imports of grains and oilmeals to fill the gap between demand and supply at the artificially low food prices. This can be clearly seen in the available data (Figures 1 and 2). Net grain imports in 1969 were 3.6 million tons. In 1970, net grain imports rose to 10.1 million tons. By the end of that decade, annual net grin imports were consistently in the 13-to-14-million-ton range. Soymeal imports show a similar pattern, rising from 1.2 million tons in 1969 to around 4 million tons each year by the end of the 1970s.

Rising net food imports are not a problem by themselves, rather it depends on how the imports are financed and how the governments market those imports. Eastern European governments made very poor decisions regarding financing the imports. First, they tapped the large pool of loanable funds in international markets following the oil price shock of 1973. These loans were obtained at variable short-term interest rates, and the ability of Eastern European nations to repay them was limited. Second, Eastern Europe relied heavily on concessional purchases, such as CCC credit programs. Third, they financed large and growing consumer subsidies through government budget deficits rather than reducing the subsidies. That is, they substituted debt financed imports for price reform. Fourth, because the loans had to be serviced in scarce hard currency, they diverted much of their hard currency to servicing the debt on a consumption activity instead of using the funds for investment. This compounded the budget deficit. As imports rose, the subsidies rose, and this disastrous cycle continued.

To illustrate, assume that the world price of grain in the 1970s was $5 per bushel, while the subsidized price to users in Eastern Europe was $1 per bushel. Over the decade, Eastern Europe bought 108 million tons of grain. The actual cash outlay for subsidies on those imports would be$16 billion. But these nations did not pay the loans for this grain purchased, rather the money was borrowed and rolled-over year after year through new loans. Lenders agreed to this as long as the interest was covered. The actual increase in external debt on all goods for Eastern Europe between 1971 and 1981 was 78 billion dollars. When world interest rates rose sharply in the early 1980s, the consequences of this strategy were quickly apparent. Some nations could not service the debt in hard currencies. Others limped along by paying what they could when they could. Romania squeezed domestic consumption and used exports to service its debts.

The import strategy of the 1970s left Eastern Europe in a terrible economic mess. Most nations had large foreign debts they either struggled to pay or could not pay. Government deficits resulting from the subsidies were large, thereby creating inflationary pressures in the economy. The consumer subsidies and low producer prices, which were the source of the problem in agriculture, remained. Where prices were controlled, this inflation was reflected in shortages of goods and excess cash in consumers’ hands. Where prices were “free” in the small private markets, prices rose sharply. The resulting inflation eroded consumer purchasing power.

The Future

By the late 1980s the economic problems were so severe that they could no longer be ignored. In some countries the pressure for change came from the populace below, as in Poland. In other countries, like Yugoslavia and Hungary, the need for reform was recognized by those in power. Some nations proceeded slowly and relatively orderly; others, such as in Czechoslovakia, experienced sudden but orderly changes in government. Hungary and Yugoslavia toyed with limited reform within the socialist system. Romania, in contrast, exploded.

The future for these economies is very uncertain. In the near term, economic reforms, such as price increases and cuts in government subsidies, will mean austerity. Incomes will be eroded by the price rise and the cut in subsidies. Inefficient state industries will lose their protection and be forced to downsize or to go out of business. This will result in unemployment and a further loss in per capita income. There is concern that governments experimenting with

Political and economic reform after 40 years of central planning will become unstable as economic conditions worsen. The outcome will depend on the willingness of Eastern Europeans to tolerate an extremely difficult economic period for increased political freedom and economic reform.

For agricultural trade, the lean years ahead in Eastern Europe suggest that most export sales to Eastern Europe will be made on a concessional basis. It is doubtful that Eastern European nations can afford large commercial imports. The United States and Western Europe already are sending increased food aid.

But the extent of food aid assistance is controversial. A recent editorial in The Economist magazine warns against massive U.S. and Western European food aid. The view expressed is that such assistance in the 1970s is what created the foreign debt problem in the first place. Without that aid, Eastern European governments would have had to raise food prices earlier and would not now be in such a terrible economic condition. The Economist recommends only minimum short-term aid to keep the present governments in power, and that the majority of the aid be long-term assistance designed to improve the functioning of these economies and to facilitate the transition to a more democratic political system. Such aid would include management training and infrastructure development. The aid would be intended to improve the operation of their markets rather than food give-away efforts that would depress agricultural prices and allow governments to avoid economic reform.

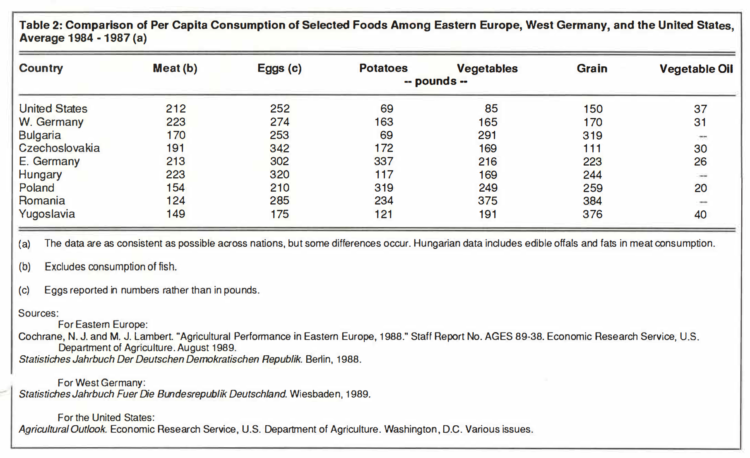

There appears to be little commercial demand in the short run. What about the long run? Successful economic reform could open possibilities for major food exporters such as the United States, Western Europe, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, and Australia. With revived economies, Eastern Europe could again become a growth market. However, the present composition of imports would likely shift. Eastern European consumers eat more grain directly and less meat than consumers in the West. (See Table 2 for a comparison of per capita consumption of major food items in Eastern Europe, West Germany, and the United States.) Per capita income increases following reform could lead to higher meat consumption and less direct human use of grains. Livestock feeds in Eastern Europe also have a much greater grain component and a smaller protein share than Western rations. As Eastern Europe evolves toward western consumption patterns, grain use in livestock feeds could decline and the use of oilmeals, like soymeal, could increase. Thus, a growth in soybeans and soybean meal imports is possible. Grain use may grow as well, but changes in diet and in livestock feed composition may limit this growth.

If the reforms are successful, agricultural production could increase in Eastern Europe. Prior to World War II, much of Europe’s agricultural production was in the East. Hungary and Romania have soils and a climate that offer a real potential for increasing output given more realistic price signals. Polish agriculture appears to be inefficient. Most of the farms are private and small. They tend to be labor intensive with little application of modem technology. It is not uncommon to see grain harvested by hand in Poland and much of the sector still uses horses. Agricultural output has been limited by the lack of modem inputs through the state-controlled distribution system. The difficulties in Eastern European agriculture are reflected in grain yields. Grain yields in the United States, which uses a land-extensive technology, are usually one-third greater than in Eastern Europe. In 1988, Eastern European grain yields were the fourth highest since 1960. Yet the U.S. drought-reduced yield for grain still exceeded that in Eastern Europe. Hence, there is much output potential if agricultural policies are reformed.

Table 2: Comparison of Per Capita Consumption of Selected Foods Among Eastern Europe West Germany and the United States Average 1984 – 1987

Summary

The economic problems in Eastern Europe have been a long time coming. Their roots lie in the centralized determination of agricultural and food prices during the past 40 years and in the import decisions of the 1970s. Currently, these nations are bankrupt, and little import demand for agricultural products, except under concessional terms, can be expected in the short-run. In the long-run, successful economic reform could mean expanded trade opportunities for farm products. The United States would face tough competition from rival exporters, especially those in Western Europe, who are well situated to supply Eastern Europe. Soybean meal could be a major beneficiary of political and economic reform as meat consumption rises and as livestock feeds include more protein.

Western nations through economic aid can assist the Eastern European nations through a difficult period of economic austerity. But whether reform is successful ultimately depends on the Eastern Europeans themselves. One can only hope that they can survive these times of trial and tribulation.