Trends in Indiana Food Processing

July 18, 2008

PAER-2008-5

John M. Connor, Professor

Three Types of Food Industries

There are three locational types of industries: supply-oriented, demand-oriented, and footloose. In order to minimize costs of location, the supply-oriented food industries must locate production close to their major material inputs because the inputs are perishable or otherwise expensive to transport relative to total manufacturing costs of production (or final product price). In contrast, the demand-oriented industries have high costs of distribution and storage relative to the finished product price. Demand-oriented industries can also be identified by a short radius of delivery zones from the manufacturing plant to the purchasing distributor’s location. Footloose industries are those for which neither assembly costs nor distribution

costs dominate.

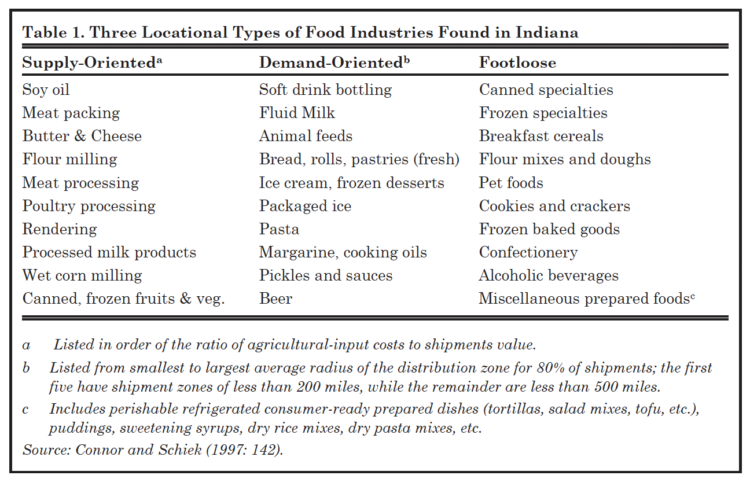

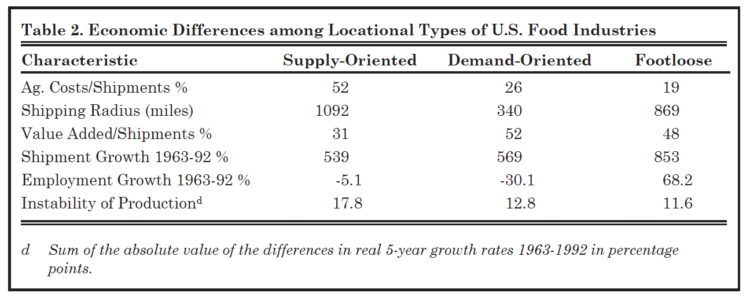

The major examples of the three locational types of industries are listed in Table 1, and their major economic characteristics are shown in Table 2. (These industries are broadly defined and may contain segments that fall into more than one locational category). For decades in the past and for the years to come, this three-part framework has at least roughly predicted food-industry growth.

Generally speaking, the supply-oriented industries produce commodities with low value-added intensity (slim margins) and low job growth. A high share of production is sold to other manufacturers (mostly other food manufacturers) for further processing, and the rest goes to wholesale distributors. Plants tend to be large in scale and located in rural areas and small towns. Because these industries are tied closely to agriculture and its volatile prices, these industries as a group have the most real output volatility. Their product markets are the largest geographically, with broad national sales and relatively high export shares.

The demand-oriented industries are where they are because of the pull of their retail customer locations. They make moderately differentiated consumer products, many of them perishable, fluffy, or high in water content. Several of the demand-oriented food industries deliver direct to retail establishments via their own driver-salespersons; delivery zones are small. High transportation-cost intensity makes their plants relatively small and mostly in or near metro areas. The leading national companies tend to own or franchise dozens of manufacturing plants across the country. These industries are relatively labor-intensive and have high large gross margins (high value added relative to sales). The share of agricultural costs in shipments value is quite low, and real output stability is high.

The footloose industries tend to assemble a relatively large variety of food ingredients from many suppliers located at all points of the compass. Products are high-value-added, highly differentiated, convenient, innovative, consumer-ready items. Many of the footloose industries make products that substitute for products formerly made in a demand-oriented industry. Partly as a result, employment and shipments growth is significantly higher than the other locational types. For most footloose industries, an optimal (minimum-input-cost) location is typically unknowable. Distribution zones tend to be multistate regions covering from one-quarter to one-half the U.S. population, for which calculating minimum shipping costs are also difficult. (Exports are minimal for most of these industries). That is why the footloose industries are fickle industries. Simple demand-and-supply economic considerations have weak effects on location investments.

Table 1. Three Locational Types of Food Industries Found in Indiana

Economic Development Implications

First it is doubtless obvious that, all other things being the same, a rational deployment of economic development effort and incentives would target footloose food industry investments – new plants and expansions. It is also clear that the locational advantages have less to do with hard-headed business calculations than with less easily evaluated factors: economies of agglomeration (found primarily in or near metro areas), the proximity of centers of food-industry R&D, the eagerness of state or local development officials, or simply managerial preferences for or perceptions of business or family lifestyles.

Second, the demand-oriented industries are ultimately primarily influenced by the spending power of consumers in the industry’s distribution zone. That zone may encompass as little as a few Indiana counties or as much as all of Indiana and its adjacent states. To the extent that Indiana is gaining population and employment relative to its neighbors, demand-oriented

food-processing will move here. The increasing ethnic pluralism of the state’s population also may stimulate demand for some of these industries’ foods. Short of educating potential investors about such demographic trends, there is little economic-development effort justified for these industries. Since the 1920s, the center of U.S. population and household spending has moved steadily to the south and west, and is expected to continue to do so. To some slight extent, Indiana may be the beneficiary of demand-driven food-plant closings in northern Illinois, Michigan, and Ohio, but in general, efforts to oppose this population shift is futile.

Third, the growth of Indiana’s supply-oriented food industries is ultimately a by-product of improved low-cost supplies of perishable or bulky raw agricultural production. These industries will relocate and expand to the extent that present and future farm production remains high for hogs, fed cattle, poultry, farm milk, rough grains, soybeans, and certain fruits and vegetables. “Grow it, and they shall come” is the watchword. The maintenance of rural roads, barge, rail connections, and associated communications infrastructure is a secondary policy area that can contribute to the reliability and low cost of agricultural inputs for the supply-oriented industries.

Table 2. Economic Differences among Locational Types of U.S. Food Industries