United States and European Consumer Demand for Genetically Modified Food in an Experimental Market

May 13, 2004

PAER-2004-4

Jayson L. Lusk

Few issues in United States (U.S.) agriculture have become as contentious as biotechnology in food production. For agricultural producers, biotechnology has the potential to lower production costs by reducing input usage. Biotechnology also has advantages of potential food and environmental quality improvements. Despite the promise of biotechnology, a number of real and perceived risks exist. For agricultural producers, one of the greatest risks of continuing to grow genetically modified crops is that of potential consumer backlash, both domestically and abroad. For example, the European Union (EU) restricts imports of U.S. commodities that have been genetically modified by imposing a moratorium on approving new genetically modified crops and through mandatory labeling laws. EU countries require labeling of genetically modified foods, and a number of large EU retailers have agreed to stop selling all genetically modified foods, effectively banning genetically modified foods for most EU consumers. The European stance on biotechnology, among other factors, has had a significant effect on US-EU agricultural trade. According to US Department of Agriculture data, US exports of corn to the EU have fallen 99% since 1995 and exports of soybean meal to the EU fell 66% over the same time period.

Understanding Demand for GMO Foods

U.S. agricultural producers need to develop an understanding of consumer demand for genetically modified foods to assess the viability of current production practices and to forecast future marketing opportunities. The conventional wisdom is that U.S. consumers are generally accepting (or perhaps unknowledge-able) of genetically modified foods. However, there is clearly some segment of the population that is adamantly opposed to use of biotechnology in food production and are willing to pay premiums for foods without genetically modified ingredients. How large is this consumer segment? What kinds of premiums will this segment pay for genetically modified foods? Is this consumer segment likely to grow or decline in the future? These questions are, at present, largely unknown.

Naturally, U.S. agricultural producers are also interested in international consumers’ perceptions of genetically modified foods, as exports account for a large portion of U.S. commodity sales. Understanding international consumer demand for genetically modified foods is complex. Take for example the EU. The EU often cites consumer food safety concern as a basis for restricting imports of genetically modified foods. However, it is possible that the cited food safety concerns are simply a way for the EU to protect domestic agricultural producers from international competition. So, are EU consumers really all that different that those in the US and if so why?

Researching Consumer Demand

Recent research undertaken by Purdue University and the University of Reading, England has begun to address these questions. In the summer and fall of 2002, a number of research sessions were held with primary household shoppers in Long Beach, CA (47 participants), Jacksonville, FL (39 participants), Lubbock, TX (80 participants), Reading, England, (108 participants) and Grenoble, France (98 participants). In these research sessions, consumers were asked a number of questions to determine their knowledge and attitudes about the use of genetic modification in food production. Then, consumers bid in an auction. Using an auction to determine how consumers value genetically modified food is advantageous because the approach creates an active market that involves the exchange of real food and real money to determine the price-premium placed on a food containing no genetically modified ingredients versus a food containing genetically modified ingredients. A substantial amount of academic research has shown that individuals’ responses to hypothetical survey questions are poor predictors of actual behavior. By using a non-hypothetical auction with real food and real money, this study avoids the bias inherent in hypothetical surveys.

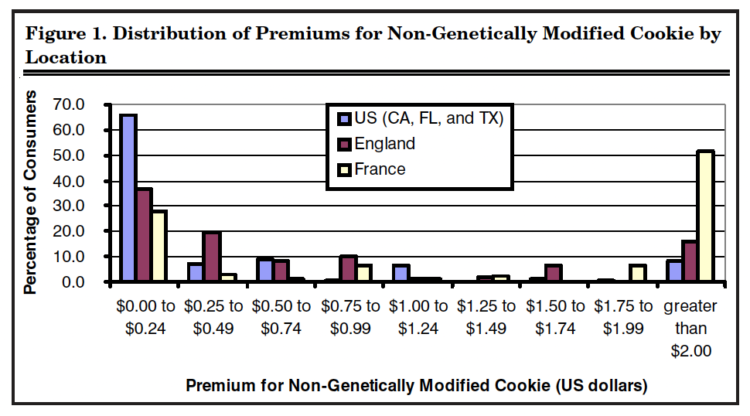

The non-hypothetical market was designed to determine the premium consumers placed

on a non-genetically modified cookie by eliciting consumers’ “willingness-to-accept” compensation to exchange a non-genetically modified cookie for a genetically modified cookie (figure 1). In this auction, consumers were given a cookie that contained no genetically modified ingredients. Then, consumers bid to exchange their non-genetically modified cookie for an otherwise identical cookie that did not contain genetically modified ingredients. The lowest five bidders won the auction and were paid the fifth lowest bid amount to exchange their non-genetically modified cookie for genetically modified cookies. All participants were required to eat the cookie they possessed at the end of the research session; auction winners ate genetically modified cookies and auction losers ate non-genetically modified cookies. The structure of the auction is such that individuals have an incentive to bid the minimum amount of money it was worth to them to exchange their non-genetically modified cookie for a cookie containing genetically modified ingredients (i.e., their “willingness-to-accept). It is worth noting that this auction operated in manner exactly opposite of that with which most readers are likely familiar. In a traditional “willingness-to-pay” auction, individuals bid to purchase an item they desire where the highest bidder(s) win the auction and pay one of the highest bid amounts

for the item. This study used a “willingness-to-accept” auction where individuals bid to accept a good they did not want where the lowest bidders(s) won and were paid one of the lowest bid amounts to take the item.

Research Results

For ease of exposition, data from the three U.S. locations were pooled together (figure 1). Clearly, U.S. consumers were much more willing to consume the genetically modified cookie than were the EU consumers. Over 65% of U.S. consumers demanded an amount between

$0.00 and $0.24 to exchange their non-genetically modified cookie for the genetically modified cookie, whereas, only 37% of English and 27% of French consumers fell in the same category. In contrast, most French consumers (52%) demanded more than $2.00 to eat a genetically modified cookie, whereas, only 16% for English and 9% of U.S. consumers demanded more than $2.00 to exchange their non-genetically modified cookie for the genetically modified one.

Figure 1. Distribution of Premiums for Non-Genetically Modified Cookie by Location

Two important conclusions can be drawn. First, on average EU consumers are much more concerned about consuming this particular genetically modified food than are U.S. consumers. But averages don’t tell the whole story. The second important conclusion is that there is significant heterogeneity within each country, with significant segments of the English and French populations having both relatively low and high concern for this genetically modified food.

Although this study only relates to consumer demand for one particular type of genetically modified food (a cookie), survey questions reveal similar relationships between the U.S. and EU consumers when they are asked about general acceptance and concern for genetically modified foods. EU consumers were more concerned about, and less accepting of, genetically modified foods on average than were U.S. consumers. Having established that there are, in fact, differences in U.S. and EU consumers, the interesting question becomes why these differences exist. To address this issue a number of survey questions were asked. In general, cross-country differences might arise because of differences in knowledge; trust; general attitudes toward the environment, food, and technology; and perceptions of the benefits and risk of biotechnology.

- In terms of subjective knowledge (i.e., the self-reported level of knowledge on a scale of 1 = very unknowledgeable to 9 = very knowledgeable), consumers in all three countries believed they were relatively unknowledgeable about issues related to genetically modified foods; however, the French consumers had a much higher level of subjective knowledge than U.S. and English consumers. However, in terms of objective knowledge about genetically modified foods, which was determined by asked a number of textbook true/false questions; there was little difference across countries. So, while French consumers believed they were more knowledgeable about genetically modified foods, they are no better at correctly answering true/false questions about genetically modified foods than were U.S. and English consumers. Overall, responses to the true/false questions indicate that objective knowledge levels in all three countries are moderate to low.

- The French and English consumers were much more concerned about the environment in general and viewed genetically modified foods as a greater risk to the environment than U.S. consumers.

- English, and especially French, consumers were much less optimistic about the ability of technology in general, to improve society and civilization than were U.S. consumers.

- French and English consumers were much less trusting of information about genetically modified foods from their federal food regulatory agencies (i.e., the FDA, USDA, and their international equivalents) than were U.S. consumers. In addition, U.S. consumers were more trusting of agribusinesses than were the EU consumers. In contrast, the EU consumers were more trusting of information about use of genetic modification in food production from activist groups such as Greenpeace than were U.S. consumers.

- In general, there was no relationship between consumers’ demographic characteristics such as income, education, race, and religion and acceptance of genetically modified foods. Age had a slight influence on acceptance, with older consumers being more accepting of genetic modification in food production than younger consumers.

- Within the U.S., California consumers were more concerned about the use of genetic modification in food production than were consumers in Texas and Florida. In fact, consumers in California, on average, demanded up to twice as much money to consume a genetically modified cookie than consumers in Texas and Florida.

Implications, Opportunities and Concerns

These results have a number of implications for U.S. agricultural producers. First, results suggest that roughly 10% of U.S. consumers are adamantly opposed to use of biotechnology in food production and this number is much higher in England (16%) and France (52%). Thus, it appears there are viable niche marketing opportunities in the U.S. to promote and sell “GMO free” foods. Some of this market is currently being met by firms that typically bundle “GMO free” and organic attributes, but there may be room for more players in this arena. These results also imply that US exporters will likely encounter strong resistance to future efforts at liberalizing the EU’s policies on genetically modified foods. Although products such as Round-up Ready soybeans are approved for sale in the EU (albeit with a mandatory label), little is actually sold. One of the major impediments to entering the European markets with genetically modified foods are the European food retailers who have decided to effectively ban genetically modified foods from their shelves. One might question why European food retailers ban genetically modified products even though most European countries have labeling laws for genetically modified food such that consumers can pick-and-choose as they please. One answer may be the retailers’ fear of reaction from consumer and environmental activist groups, which tend to be larger in Europe than in the U.S. Helping European retailers devise strategies to contend with activist protests could help open the door for US exports. Ongoing research on consumer behavior is aimed at determining the extent to which consumer aversion to genetically modified foods will change in the future due to education, communication strategies implemented by the biotechnology industry, the popular press, and future scientific discoveries.