What Will the 2014 Farm Bill Mean for Midwest Agriculture?

April 13, 2014

PAER-2014-1

Roman Keeney, Associate Professor

The Agriculture Act of 2014, better known as the 2014 Farm Bill was signed into law on February 7, 2014. The process of getting to a new farm bill was difficult, spanning more than two years. Many specific provisions of the farm bill will depend on how the United States Department of Agriculture interprets provisions of the bill and implements the programs. Indications are that initial signup for new farm commodity programs may not take place until at least September for crops to be harvested in 2014.

The new farm bill is a major overhaul of commodity policy in the United States. This article provides an overview of those changes, introduces some of the decisions Midwest farmers will be making, and considers the continuing evolution of U.S. agricultural policy.

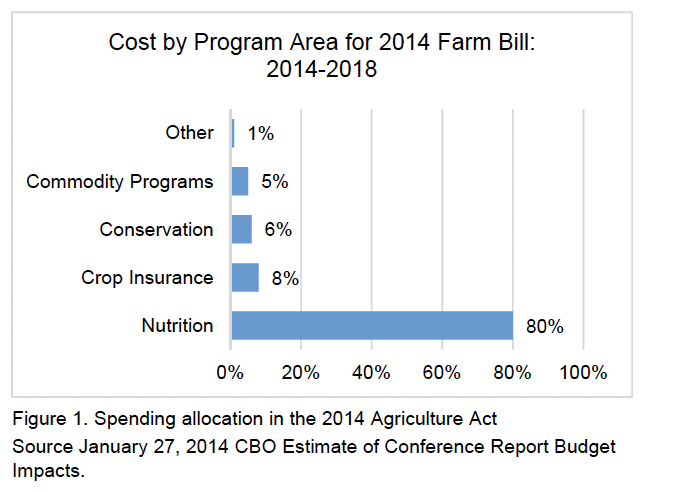

Calling the farm bill a law about “farming” has long been a misnomer since the majority of the spending is not directed toward production agriculture. The long economic recession and the high farm prices over the past six years resulted in a significant shift in farm bill outlays. The 2008 farm bill was projected to have about seventy percent of spending dedicated to nutrition assistance programs. However, economic conditions resulted in dramatic increases in benefits for programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), while farm commodity spending shrank due to high prices which triggered smaller commodity based payments.

High spending on nutritional programs, the fact that farmers were receiving direct payments when the sector had record high farm incomes, and the need for budget control and deficit reduction led Congress to consider reforms in the farm bill. This made both nutrition spending and the fixed direct payments major targets. With rural agricultural interests trying to protect agricultural spending and urban interests fighting to maintain SNAP benefits the farm bill became one of the most contentious in history. As a result, budget reform pressure split the rural-urban coalition that has traditionally passed farm bills.

In 2013, the House Agricultural Committee’s proposed a comprehensive farm bill but that was rejected by the full House vote. This action was closely followed by a set of maneuvers to split the bill into two pieces; one covering production agriculture and the other covering food assistance. Eventually, the House was forced to rejoin their separate farm and food bills in order to conference with the Senate.

What resulted was a farm bill that allocated spending similarly to what has transpired over the past five years, with the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections estimating that 80% of the outlays would flow to food assistance programs (see Figure 1). Production agriculture would receive benefits through crop insurance (8% of estimated outlays) and commodity programs (5% of outlays). They would also receive some of the benefits under conservation programs (6%). All other programs such as trade, credit, rural development and Extension and research represent only 1% of outlays combined.

Figure 1. Spending allocation in the 2014 Agriculture Act

Source January 27, 2014 CBO Estimate of Conference Report Budget Impacts.

Farm Program Choices

The way outlays are made to the agricultural production sector will be quite different as the 2014 farm bill represents the most dramatic change in farm programs since the 1996 move to fixed direct payments. The new bill wipes away direct payments that represented a constant revenue source of about $5 billion dollars per year. Direct payments, counter cyclical payments (CCP), and the average crop revenue election (ACRE) programs have been replaced by a menu of programs that farmers can choose among to provide safety net protection and to complement crop insurance on their operations.

Farmers will choose among three alternatives when commodity program enrollment begins through USDA’s Farm Service Agency (FSA).

- Price Loss Coverage (PLC): Is a price support program that triggers payments when national marketing year average prices fall below fixed reference prices set in the bill

- Agricultural Risk Coverage-County (ARC-C): Is a revenue support program with payments triggered by county revenues per acre falling below county benchmark revenue levels

- Agricultural Risk Coverage-Individual (ARC-I): Is an alternative to ARC-C with payments triggered by the individual farm’s revenue per acre falling below their individual farm’s benchmark revenue

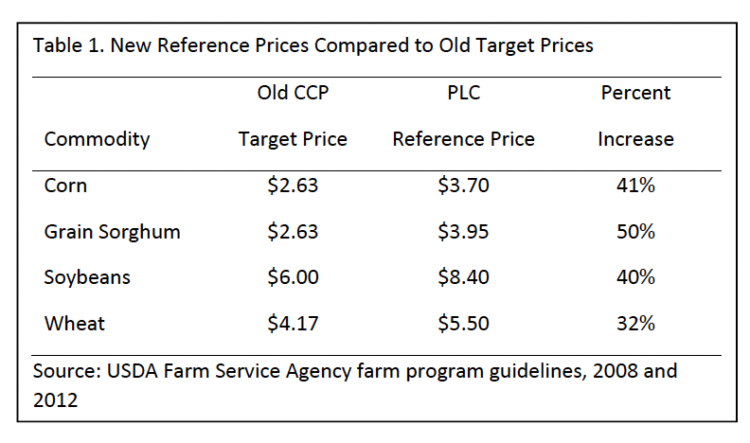

The PLC program can be viewed as a straightforward updating of the old CCP target prices, but now called “reference prices.” For Indiana’s primary crops the price protection of the new PLC program relative to the old CCP is an increase of about 1/3 to 1/2 (see Table 1). Both corn and soybean reference prices are around forty percent higher in the new farm bill with payments that trigger when national marketing year average prices fall below $3.70 per bushel for corn and $8.40 for soybeans. This price protection is in place beginning at the reference price and the amount of the payment increases until the loan rate floor price for the commodity is reached.

The ARC program will use recent yields and prices to establish a benchmark revenue level per acre. These benchmark revenues per acre are established by the preceding five years’ information on prices and yields either for the county (ARC-C) or the individual farm (ARC-I) depending on the option. If revenues fall below 86% of the calculated benchmark revenue per acre, then payments are triggered. Per acre payments increase with steeper declines in revenue up to a maximum of 10% of the benchmark revenue per acre. The five year average benchmark revenue is calculated as an Olympic average, with both the lowest and highest yield and the lowest and highest price removed from the calculation.

Table 1. New Reference Prices Compared to Old Target Prices

Additional Considerations

The program enrollment choice farmers make this year will require analysis of the farm’s performance and expected payout under all three alternatives. They also will need to take into account the following provisions:

- The enrollment in any of the options is permanent for the five year life of the farm bill

- Failure to enroll in 2014 places a farmer automatically in the PLC program beginning in 2015 with no payment eligibility for the 2014 crops

- If choosing either PLC or ARC-C, a farmer may enroll in different programs commodity-by-commodity. As an example on the same FSA farm, the corn base acreage could be enrolled in PLC while soybeans are enrolled in ARC-C

- If choosing the ARC-I program all base acres on that FSA farm must be enrolled in the ARC-I program

- Base acreage can be reallocated to be in the same proportion as the actual planted crops during 2009 to 2012. This will be an elective as each farm can stay with the current base, or reallocate.

- Those electing PLC can update their FSA yield base to 90% of that farm’s yields from 2008 through 2012. It is likely that most electing PLC will also want to update their yields.

A companion article offering a first look at the commodity programs and how they compare in terms of payments is available in this issue for those interested in beginning the process of analyzing the three alternatives.

Dairy represented one of the most contentious issues in the farm bill, with supply control proposals receiving broad support and strong resistance from House leadership. The final program represented a compromise that averted supply management but does provide limitations to help smaller scale operations remain more competitive. While there is no specific commodity support for livestock producers in the bill there are provisions for a disaster program to assist producers affected by weather and drought conditions. The severe impact of the 2012 drought and devastating weather in the mountain west were both strong political motivations that helped move the farm bill to final passage despite many lawmaker’s reservations about the lack of spending cuts.

How Has Ag Policy Changed?

Farmers have dealt with more than two years of uncertainty surrounding the commodity program system that influences farm decision making. The elimination of direct payments has been a known factor throughout the process meaning that some $5 billion of annual payments that had no influence over on-farm decisions were going to be eliminated and replaced by a set of payments that are tied to market outcomes. Farmers will be able to choose among three programs regarding how to best establish a safety net for their farm and offset some of the risk of farming. Since the bill is now law, farmers can begin the process of learning about program alternatives and collecting FSA yield and acreage bases for each of their farms. They can also begin to evaluate how government programs integrate with their crop insurance protection. However, final details of the program will likely not be defined by USDA until this summer, and then farmers will have time to learn about, and evaluate the alternatives for their farms.

In the long process of getting to a new farm bill, several “big ideas” were floated. Most notably was the separation of farm programs and food assistance into separate legislation. Whether this is an idea that gains traction for the next farm policy debate or falls to the wayside remains to be seen. The process of the 2014 farm bill was begun in the fall of 2011 as reaction to the budget reform agreement passed that summer. In the end, most of the proposals to achieve budget savings fell by the wayside and the majority of spending was preserved. The new farm bill offers farmers more options and variety to match the government safety net program to their operation and their management style. However, the same bill could cause government spending to rise dramatically if crop prices fall precipitously. In addition, the individual farm program choice (PLC versus ARC) could impact whether individual farms have an effective safety net and whether there will be demands for additional emergency funding to fill in gaps. Greater farm program expenditures could inflate current budget deficit issues already faced by the federal government.