What’s the Right Rent Now? How Can it Be Kept Right Easily?

July 13, 2000

PAER-2000-08

Howard Doster, Purdue Extension Economist

The short answer to the title question is that average rents are too high to be sustained by most tenants. While no one knows the actual yields and prices yet for 2000, we do know that government payments for 2001 are scheduled to be much lower than for 2000. Many leases for 2001 will be negotiated this summer and fall, long before Congress considers any possible extra payments for 2001.

What’s the Theory?

As economists, we study how persons trade with each other, and then predict how they will trade with each other. We have learned that the residual returns go to the scare resources. In crop farming, the scarce resources are productive land and top management. When times are good, land rents increase; in bad times, rents eventually drop. During transition times, one party receives excess returns, and the other suffers.

What’s the Practice?

Once they’ve negotiated a lease, many landowners continue the same lease with the same tenant for several years. When tenants receive unexpected revenue from high yields or prices, or government payments, some tenants report they sometimes share their excess revenue with their landowner. When revenues are unexpectedly low, some Indiana landowners report they sometimes refund part of their rent.

Some landowners have cash leases with adjustors for yield and/or prices that are based on the tenant’s reported performances, but these performances may not be timely.

Few landowners have adjustors for government payments, even though the payments have varied greatly in recent years. FSA pays the person who is at risk, the tenant in a cash lease. (However, the tenant and landowner can have a lease that pro-vides for the tenant to pay the landowner all the government payment. Such a lease shifts the risk of uncertain payment amounts to the landowner.)

Very few leases provide for between-year adjustments in base rent. Therefore, leases must be renegotiated to reflect current economic conditions when expected prices or government payments change greatly.

What’s a Better Way?

I think landowners and tenants can create leases that provide for adjustments that are appropriate for cur-rent economic conditions. Later, in this paper I will illustrate one such lease. The adjustments can account for 100% or for 50% of the changes that occur after the lease is negotiated. Tenants are expected to pay more rent for leases with these adjustment terms. The adjusted rent will be less than the base rent in low income years and more than the base rent in high income years. With this lease, the tenant does not need to report actual performance to the landowner.

How Much Have Returns and Rents Varied Recently?

Per acre crop returns have varied considerably over the past five years, and many persons expect returns to vary considerably over the next several years. Yields often vary widely from year to year. Crop prices increase when forecasted inventory carry-out is small; other years, prices decrease until someone is willing to own bushels that may not be used the next year.

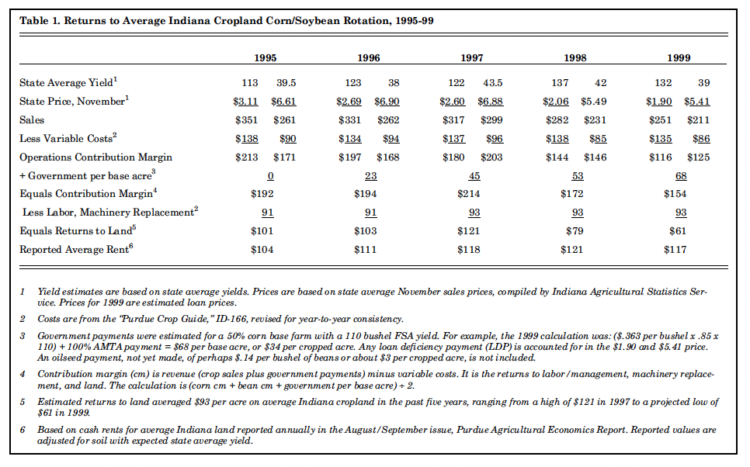

In the past five years, government payments have varied from zero in 1995 to an estimated $68 per acre in 1999, as shown in Table 1, “Returns to Indiana Cropland.” In addition to increasing each of the years from 1995, government payment increases have been announced after leases were negotiated in four of the five years. (If the just-passed Senate bill becomes law, government payment increases will have been announced after leases were negotiated in five of the last six years.)

In 1996, the Farm Bill was passed in May, after some crops were planted. The actual 1997 payment was included in the 1996 Farm Bill. However, in the fall of 1998, the 1998 payment was increased 49%above the provisions included in the 1996 bill. In the fall of 1999, the payment was increased 100% above the amount provided for in the 1996 bill. In 2000, the May 2000 Senate bill also increased the payment 100%above the amount provided for in the 1996 legislation. Thus, tenants have been forced to base their rent offer on possible additional payments. Payments from the 1996 bill are scheduled to continue at a declining amount through 2002.

As shown in Table 1, average returns during the five years varied more than reported average rents. Note the numbers on the line identified as “Contribution Margin.” Contribution margin is revenue, including crop sales and government payments, minus variable costs. It is the return to the resources: labor/management, machinery replacement, and land. The per acre contribution margin was $192 in 1995, increasing to $214 in 1997, then decreasing to $154 in 1999. Thus, over this period, the Indiana average contribution margin varied by $60 per acre.

As shown in Table 1, reported average rent increased from $104 in 1995 to $121 in 1998, before drop-ping to $117 in 1999. Thus, over this period, the Indiana average rent var-ied by $17 per acre.

For 2000, suppose yields are at trend amounts (135.8 bu corn and 43.5 bu beans), prices are at loan rates, variable costs are increased an average of $6 per acre, and government payments are at the scheduled $31 per acre. Then, as compared to the 1999 amounts in Table 1, the contribution margin is $146, down $8 from 1999. If the government pay-ment is doubled as in the Senate bill, the contribution margin is increased to $161. Then, by subtracting $93 from these numbers, the return to land is either $53 or $68, well below the likely reported average rent for 2000.

What Is Right Rent?

What is the right rent? You may ask that question as you study Table 1. Was rent too low in 1995 and right in 1999? Or was it about right in 1995, 1996, and 1997, as suggested by the relationship between the bottom two lines, “Return to Land” and

“Reported Average Rent”? In those years, the difference was only $3-8. However, in 1998 and 1999, the difference was $42-56, even after including the extra government payments of 49% and 100%.

Without providing the details here, the variable costs and the labor and machinery replacement are amounts I report annually in the “Purdue Crop Guide” (ID-166). I think they are representative values for Indiana tenants. Therefore, I think the evidence suggests average rents were about right in 1995-97 and much too high in 1998 and 1999.

How can tenants pay rents that are too high? Some can’t, and they exit the industry. Others can pay more rent because they are more productive, have lower costs, have non-crop income, have some lower rents (including zero rents on debt-free owned land), and/or can postpone machinery replacements. Based on reported combine and trac-tor sales, most farmers have postponed machinery replacement. However, some farmers are buying the new, larger sized combines and are renting additional land. These farmers can have lower per acre labor/management costs. Nevertheless, I think rents are too high to be sustained at the 1999 average amount, given the current contribution margins.

I expect continued consideration of government policy alternatives to somehow increase contribution margins. Somehow, I think the two bot-tom line amounts in Table 1 for the next five years will become closer together than the amounts reported for 1998 and 1999.

To me, the question, “What is the right rent?,” creates a problem. As an economist, I read a market rent sur-vey to learn what buyers are paying and sellers are accepting. I have reported these amounts. As an economist, I also calculate returns and costs to estimate what tenants can afford to pay. Based on the above two economic analyses, I conclude aver-age rents are currently not at a sustainable or equilibrium amount. Thus, I say that rents are not “right” now. Many landowners are getting excess returns, and tenants are suffering.

Is it Time for a Lease Change?

In theory, except for changes in the number of prospective tenants, when expected costs, yields, prices, or government payments change, tenants are expected to adjust their rent bids so that the returns to their resources remain about the same. This theory is the basis for presenting the various adjustors in this paper.

Table 1. Returns to Average Indiana Cropland Corn/Soybean Rotation, 1995-99

If landowners permit bidding, rents are set by prospective tenants. It’s relatively easy for tenants to bid up rents when crop prices or government payments cause an increase in the expected contribution margin. Prospective tenants tend to bid most of the expected returns above their other costs into rent.

After expected prices and/or government payments fall significantly, neither present tenants nor prospective tenants should be expected to bid the same terms for the next year that seemed appropriate for the previous year. But that’s what they do if they don’t renegotiate their leases or have adjustor terms in share leases as well as in cash leases. Few leases, either share or cash, include adjustor terms. Perhaps more leases should contain adjustor terms. With appropriate adjustor terms, tenants can start each new year expecting to get the same contribution margin as when the base was first negotiated, thus reducing stress on both parties.

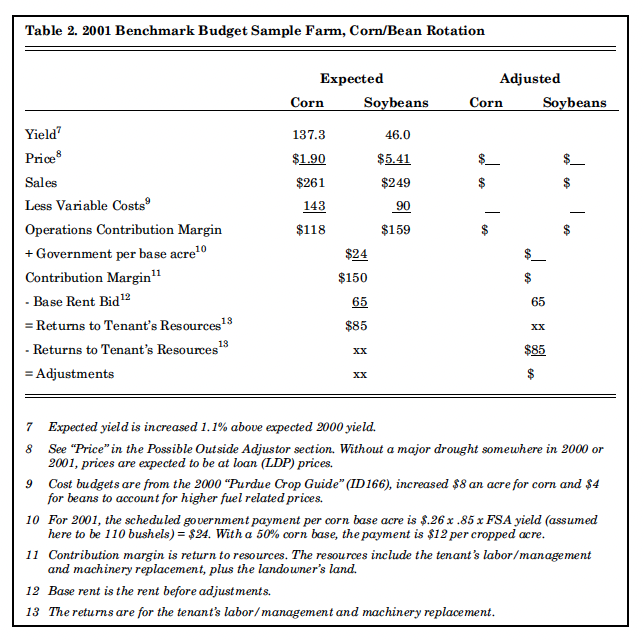

Landowners could offer tenants the opportunity to start each new year expecting to get the same contribution margin as when the base rent was negotiated, thus reducing the need to renegotiate the lease. (See Table 2. 2001 Benchmark Budget.) Without this opportunity, when economic conditions change, one party benefits and the other party suffers. Many tenants are likely paying more rent in 2000 than if their leases had been renegotiated for 2000. Unless leases are renegotiated for 2001, many tenants will pay higher rents in 2001 than now appears to me to be justified.

Table 2. 2001 Benchmark Budget Sample Farm, Corn/Bean Rotation

Some leases continue unchanged for several years. Some people argue that good years get offset by bad years, However, with mostly one year leases, there is no guarantee that one party will “get even” with the other. Also, currently, there is no guarantee what the next government program will be.

Landowners create lease terms. If landowners permit tenants to compete for their land, prospective ten-ants determine the amount of the rent by their bids. It may be time for landowners to create lease terms that provide for the landowner to expect to realize the residual returns to land each year, thus reducing the stress in either party to renegotiate the lease. With this feature, land-owners can expect to have more variable returns than landowners with cash rent leases and no adjustors. Their income variability will be simi-lar to the variability experienced by owner-operators and cash rent ten-ants. With this feature, perhaps ten-ants will bid higher rents than if they don’t have this provision. Ten-ants surveyed at the 1998 Purdue Top Farmer Crop Workshop said, on average, they would bid $13 per acre more for a lease with this feature. That’s comparable to some crop insurance payments, but the money goes to the landowners.

Once a lease is negotiated, changes can occur in costs, yields, prices, and government programs. Cost changes are generally small compared to year-to-year yield and price changes. However, an adjustor lease can include recognition of cost changes.

Cash Lease Adjustors

In a cash lease, the landowner allows tenants to set the cash rent by the amount of their bids. In calculating their bids, tenants consider or can consider the following:

- Their skills

- Their risk-taking ability

- Their other opportunities for using their resources

- Their competitors

- Their expectations about costs, yields, prices, and government payments on the landowner’s farm.

If landowners were to create a benchmark budget with their expectations for their own farm such as shown in Table 2, they could ask their tenants to base their rent bids on the costs, yields, prices, and government payments used to calculate the benchmark budget. The landowner could then subtract the selected tenant’s cash rent bid from the rotation contribution margin to find the returns to the tentant’s resources.

One year later, instead of re-opening rent negotiations, the landowner could re-calculate his/her benchmark budget for the upcoming year. To find the tenant’s rent for the next year, the landowner would merely subtract returns to the ten-ant’s resources calculated the previous year from the landowner’s owner-operator rotation contribution margin. By paying this rent for the next year, the tenant expects to have the same earnings, (returns to his/her resources) as in the year the lease was first negotiated.

To illustrate, the winning tenant for 2001 pays $65/acre in base rent for the Table 2 average soil farm. Then, based on the landowner’s benchmark budget, the tenant’s return is $85 ($150 minus $65). Because of his superior performances, the winning tenant likely expects to realize higher returns to his resources than the $85 shown in Table 2.

Suppose that, after harvest, the Table 2 adjusted contribution margin is calculated to be $160. Then, $160 minus $65, the rent bid, minus $85, the tenant’s expected returns, equals$10, the adjustment amount that the tenant pays the landowner.

Suppose that the landowner’s benchmark budget for 2002 shows a rotation contribution margin of $165, an increase of $15 per acre. Then,

$165 minus $85, tenant’s expected returns, equals $80 in base rent for 2002, an increase of $15 per acre.

Share Lease Adjustors

The 50-50 crop share lease accounts for changes in prices, yields, costs, and government program payments. Each party realizes 50% of the changes.

Tenants with 50/50 leases negotiated for, say, 1997, should recognize that their 50/50 lease sharing accounts for only half of the $64 change between the 1997 contribution margin of $214 and the 1999 contribution margin of $150 in Table 1. Thus, if prices stay at lower levels, such 50/50 tenants will also realize low returns to their labor/management and machinery resources. Likely, these tenants could renegotiate a more favorable 50/50 lease for 2001.

Historically, landowners of low quality land include incentives to tenants to get them to accept 50-50 leases. On high quality land, tenants have been able and willing to make privilege payments in order to get 50-50 leases. I think landowners should increase their incentives payment for 2001, and, assuming prices are at loan levels, payment should be made on all but high quality land.

I propose that landowners adjust their leases at the beginning of each lease year. If

expected returns are lower, rents will eventually be lower by about the same amount. The questions are “when” and “how.” Make the adjustment at the beginning of each year, and reduce stress. Until rents change, one party gets the lease benefits, while the other party suffers.

Outside-The-Farmgate Adjustor Leases

By using outside-the-farmgate adjustors, tenants can solve four problems related to their landlords.

- With outside adjustors, tenants can buy all the inputs and sell all the outputs and not have to segregate either by landowner.

- With outside adjustors, land-owners need not worry about when their crops are actually planted or harvested.

- With an adjustor lease, the risk of no increase in government payments is transferred to the landowner.

- With outside adjustors, tenants realize 100% of their actual performance.

Here are the features of outside adjustor leases. A landowner pre-pares a so-called benchmark budget for his soil such as is shown in Table 2. Landowners may use one of the budgets for low, average, or high yielding soil published annually in the “Purdue Crop Guide,” ID-166. The landowner can indicate how adjustments are to be made. The landowner can take bids from prospective tenants of his choosing and accept the bid he/she wishes, which may not always be the highest bid.

Suppose the landowner offers to take 50% of outside-the-farmgate changes in prices, yields, costs, and government program payments. This is a 50-50 share lease, but with the adjustor benefits listed earlier.

As with more conventional 50-50 leases, this lease also needs to be adjusted at the beginning of each year. The adjustment can be to change the base rent so the tenant has the same expected contribution margin as in the first year of the lease.

Tenants should recognize the features of the adjustor leases limit their upside gains as well as their downside pains. In a 100% outside adjustor lease, the tenant locks in his expected contribution margin for the duration of the lease, except for the generally small gains or losses he/she experiences because of his/her actual performances. There-fore, in a 100% adjustor lease, the calculation of the current year rent includes all the current year change in the outside adjustors that were used.

At the beginning of each year in a 50-50 outside adjustor lease, the base rent should be adjusted so that the tenant’s expected contribution margin is the same as in the land-owner’s benchmark budget when the lease was negotiated. This means that the landowner’s benchmark budget for the next year includes 100% of the current year changes in the outside adjustors that were used. During each year, the tenant and landowner then share equally in the changes in the outside-the-farmgate changes in prices, yields, costs, and/or government programs.

With both 100% and 50-50 adjustor leases, the tenant takes 100% of the risk for actually producing and marketing the crops. Therefore, the tenant can expect to earn more rewards than when doing custom farming.

Since the tenant is responsible for the actual crop production, some landowners may be concerned that the tenant won’t use sufficient fertilizer or lime to maintain the soil tests at optimum economic levels. To solve this problem, in their lease contract, landowners can commit to applying a specified quantity of lime, phosphate, and potash, at the landowner’s expense, each year. Knowing this commitment, tenants will bid higher rents.

Some landowners may not want to create adjustor leases with bench-mark budgets on their own. Professional farm managers can perform this service and select a tenant in less time the first year than they spend in managing a farm with a crop share lease. In succeeding years, managers will likely spend no more, and perhaps less, time than they devote to either a cash or share lease.

Possible Outside Adjustors

A landowner may use any or all of the following adjustors.

- Grain prices are adjusted by the difference between the expected harvest price and an actual harvest price. The expected price might be a local elevator har-vest bid price on the date the lease is negotiated, or it might be the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) closing prices for November beans and December corn on the date the lease is negotiated.

If the futures prices are used, both the landowner and prospective ten-ants will want to recognize that the tenant’s expected contribution margin includes an amount to account for the expected local basis, the difference between the CBOT futures and the local elevator price. Further, the tenant will be at risk to decide when to lock in the basis with a local buyer.

If the futures price is used, the “actual” price can be, say, the aver-age closing prices of the two futures on the last two Wednesdays in October and the first two Wednesdays in November.

- Yields. Landlords can adjust their farm-budgeted yields by the percentage change between expected yields and reported average county yields. The percentage change in county yields will not always be the same as the percentage change in yields on a specific farm. Thus, the tenant is also taking yield risk because of county variation in weather. On both a 50-50 and 100%outside adjustor lease, the tenant is taking 100% of the actual yield variation on the rented farm.

If the landowner wants to have a share of the actual crop or if the local FSA office requires it on a share lease, the tenant could calculate expected yields on each of his/her farms. Then, once the total production is deter-mined, the bushels can be pro-rated to each farm. Using this process, the tenant doesn’t need to report input and output to each of his/her landowners.

- Variable costs can be adjusted by the percentage change from April 2000 to April 2001 for pro-duction items, interest, taxes, and wage rates paid by farmers, as reported in the USDA’s publication, “Agricultural Outlook”.

- Government payments. These payments are adjusted by the change between expected and actual government payments. If loan rates are used when prices are below loan, no separate loan deficiency payments are included.

My Lease

As the tenant, I have a 100% adjustor lease for land in a nearby state. As compared to Table 1 yields, the county yields there were much higher in 1998 and much lower in 1999. I received an adjustment of $20 in 1998 and $50 in 1999. Recently, the landowner requested, and I agreed, to continue the lease for at least three more years. Perhaps the landowner is expecting much higher contribution margins in the future. If that occurs, I will pay the landowner 100% of the increase above the ten-ant’s benchmark contribution margin. See Table 2 as an example for making the calculations.

Unsolved Problems

I identify three problems that may not be solved by adjusting rents as proposed. While use of adjustors causes a decrease in income variability for the tenant, there is the landowner’s perspective to remember, as well.

- The use of adjustors causes an increase in income variability simi-lar to that of an owner-operator for the landowner, something that some landowners consider quite undesirable. Of course, as noted earlier, landowners can expect tenants to pay more rent every year than they would pay without adjustors in the lease.

- The use of adjustors causes a decrease in the tenant’s income variability only on those rentals where the tenant has an adjustor lease. On his/her other rentals, the tenant is still likely paying excessive rent for 2000. Thus, the conscientious land-owner may feel that he/she is subsidizing the tenant and that the other landowners are enjoying the “free ride” associated with higher rental income. Of course, some landowners already subsidize their tenants by charging under the market rents.

- Landowners who need a steady return will have a cash flow problem if their needs are more than the adjusted rent in low income years such as indicated for 1999 in Table 1. To solve this problem, ten-ants might offer to loan the land-owner needed cash in exchange for a lien on the land.

Conclusion

At 1999 crop loan prices, not much Indiana cropland will be idled in 2001. Almost everybody thinks they can more than cover their variable costs other than rent. Tenants now rent from multiple landowners. Expected yield may differ on each farm, and lease terms may also differ. At the 1997 Purdue Top Farmer Crop Workshop, on average, the participants indicated expected returns from their various rentals varied by$50 per acre. Tenants have quite different production skills. At the 1997 workshop, participants estimated 25 bushels per acre difference in the production skill of their tenant neighbors on the same soil type. This 1997 survey documents the great profit differences between leases and the great productivity differences between operators.

If you’re not a low-cost producer and likely can’t become one quickly, exit the industry now. Sell out ahead of the crowd, and do something where you have a comparative advantage.

If you are a low-cost producer, stay in business. At a lower rent, pick up land that others drop. Then, perhaps drop your leases with low returns potential or re-negotiate them to give you more favorable returns. Consider outside adjustor leases.

Editors note: This article is believed to be helpful in furthering the discussion between tenants, landowners and farm managers for finding better ways to share the risk of fluctuations in the “returns to land.”

The editor, and his reviewers among the faculty feel the presentation is more opinionated than we would normally publish. However, it raises several important issues that merit discussion. This article suggests one approach, but there are others. Exploring other alternatives is an important part of the negotiation process associated with developing a lease that is equitable to the tenant and landowner.