Will China Become a Net Importer of Meat Products?

May 13, 2003

PAER-2003-4

Yijun Han and Thomas Hertel

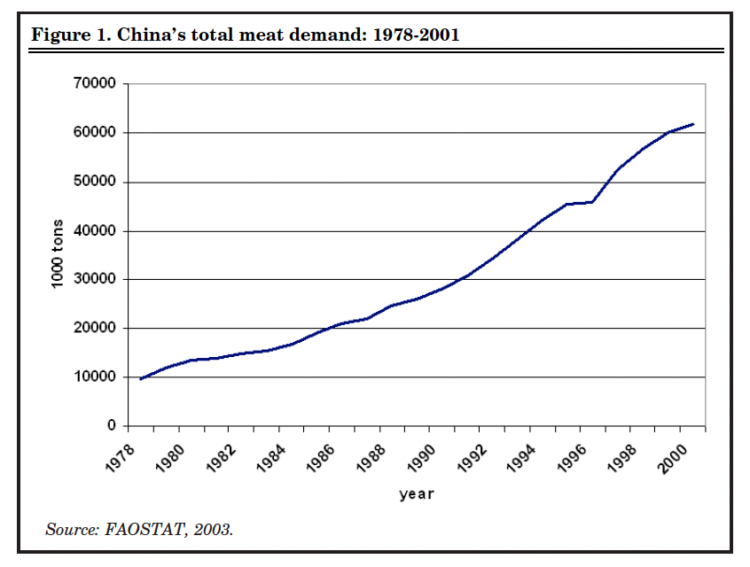

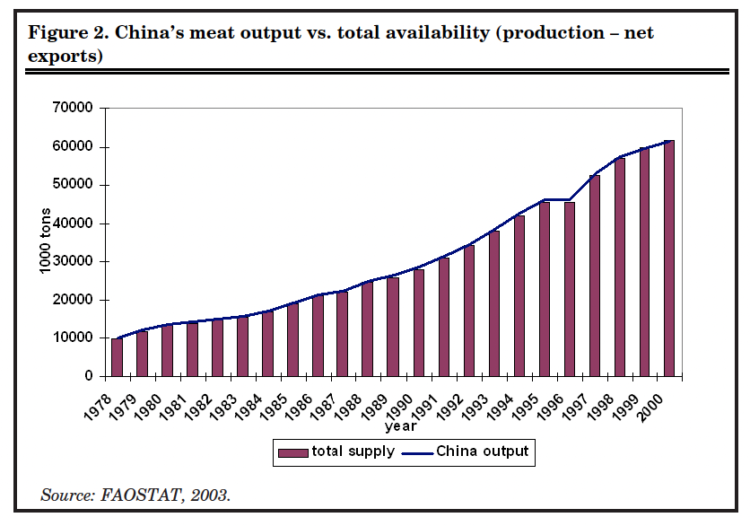

China’s massive population and rapid economic growth have highlighted its potential role in agricultural trade. Since agricultural reforms began in the late 1970’s, meat consumption in China has increased six-fold (Figure 1). Yet production has kept pace with demand, leaving trade to play a relatively minor role in the market for meats (Figure 2). Schmidhuber (2001) attributes this to increased production in remote rural areas, which are not well-integrated into the national and international economies. As demonstrated by developments since 1990, however, even a modest increase in China’s meat imports can strongly influence world markets: China is now the 4th largest market for poultry imports in the world, although the value of her poultry exports exceeds imports by about $1 billion (Han and Hertel, 2003).

Will we ever see a day when US por producers are exporting substantial quantities of pig meat to China? Or will cheap labor result in a surge in processed live-stock exports from China – akin to what we have seen in toys, clothing and other manufactured goods? Not surprisingly, many leading research institutions have explored this question, some of them using quantitative economic models. The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2000) projected that China will become a major net importer of poultry meat by 2005. In contrast, the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI, 1999) projected an increase in China’s net exports of poultry meat in the coming decades (Delgado, et al.). The Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) as well as researchers at the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) suggest that WTO accession will contribute to substantial net imports of poultry and pork by 2010 (Beghin and Fabiosa, 2001; Schmidhuber, 2001). Hertel, et al., 2000 conclude that uncertainties about macro economic conditions and productivity growth in China will dominate her future trade status, with the ultimate outcome unclear at this point.

In light of these contrasting views, our focus here is on three scenarios about the determinants of China’s future meat trade. In the first scenario, China becomes a large net importer of meat products. The second scenario, maintains China’s current net trade position. In scenario three, China becomes a major competitor in the global market for meat products.

Drivers of Change

The major drivers of change in China’s livestock trade include demand-side forces, supply-side forces, and trade policy. An assessment of their historical evolutions will facilitate projections of their impacts on future livestock trade under each scenario.

Figure 1. China’s total meat demand: 1978-2001

Figure 2. China’s meat output vs. total availability (production – net exports)

Demand

China’s changing patterns of pork and poultry consumption over the past three decades are

well-documented (e.g., Li and Wang, 1999). Rapid increases in household income, urbanization, foreign investment, and marketing have led to shifts in consumption toward non-traditional cereals and value-added products, including many derived from livestock. How-ever, the consumption structures for meat in China and the U.S. differ greatly. Poultry and beef are the most important consumption items in the U.S., whereas two thirds of meat consumption in China is in pig meat with only 19% poultry meat, 9 % beef and 5% mutton. However, the mix of meat in Chinese consumers’ diets is changing rapidly. Pig meat’s current share in total meat spending is down from nearly 90% in 1980.

Chinese and U.S. consumption patterns differ further in the composition of pig and poultry products. For example, consumption of pig feet, head and viscera, account for 7.4% of total pork consumption in China (Li and Wang, 1999), yet are negligible in the U.S. These “by-products” are highly valued in China as evidenced by the price of chicken feet exceeding that of chicken breast meat.

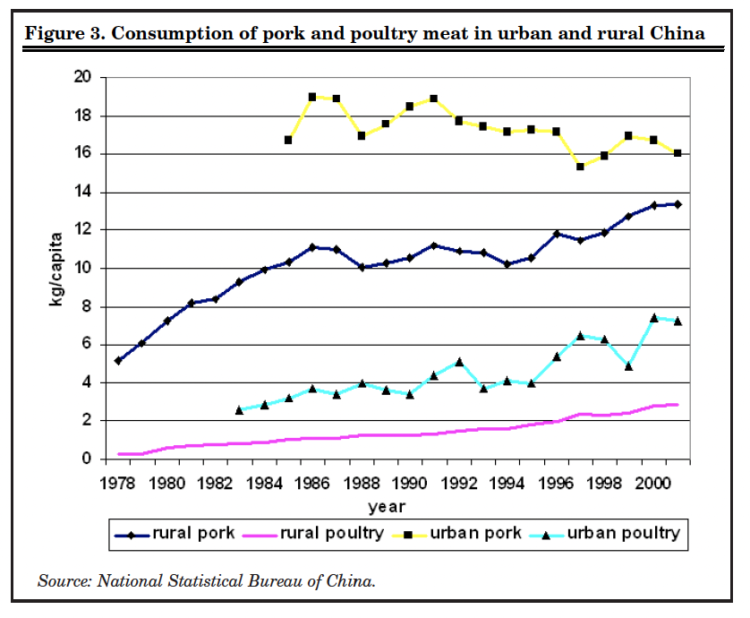

Another feature of the Chinese economy that influences meat demand is the dramatic difference between incomes of rural and urban consumers. Per capita urban income is nearly three times as high as average rural income. This difference is reflected in the respective meat consumption levels. Figure 3 shows the evolution of per capita pork and poultry meat consumption in rural and urban areas. In the 1980’s urban pork consumption per capita was about 60% above rural consumption. Since the beginning of the 1990’s, urban pig meat consumption has declined, in favor of poultry consumption, with little change in overall per capita demand for meat. On the other hand, annual rural consumption of pork has risen and it is now just 2kg per capita below urban consumption in 2001. Meanwhile, urban consumption of poultry greatly exceeds that of rural consumption (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Consumption of pork and poultry meat in urban and rural China

In many countries such a large income gap between rural and urban households would induce a mass rural-urban migration. In China, however, the household registration, hukou system prevents rural house-holds from moving permanently and obtaining services (e.g., schooling for their children) in urban areas. The hukou system, however, has not prevented massive temporary migration of workers to obtain higher paying jobs in the urban areas. Current estimates put this temporary workforce at more than 80 million people.

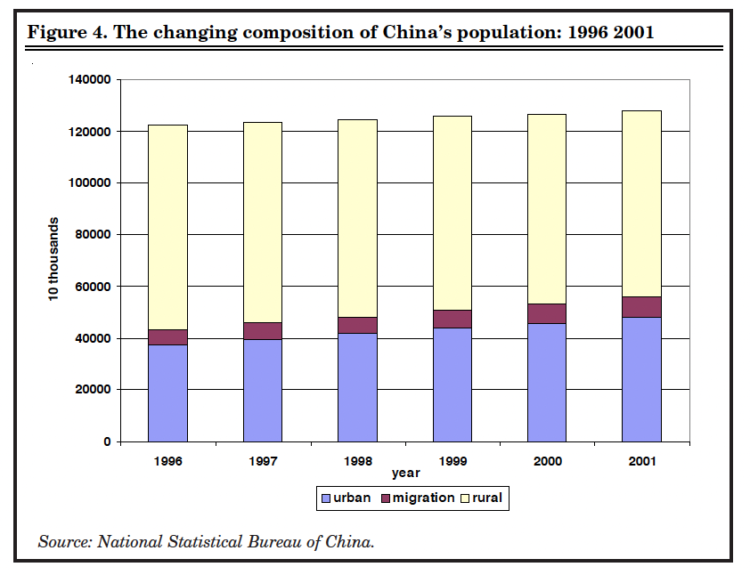

The demand for temporary workers in China has been fueled in part by the rapid increase in labor needed in the coastal provinces, the location of China’s export boom. Figure 4 categorizes China’s 1.2 billion people into rural, urban and temporary migrants. Despite a flat overall population level, the urban population (legal residents plus temporary migrants) in China has grown by about 127 million since 1996. Given the difference in consumption profiles of the rural and urban populations, this shift has clearly contributed to the change in total meat demand in China.

Figure 4. The changing composition of China’s population: 1996 2001

Future income growth in China may do little to boost per capita demand for pork products in the urban areas. Income growth in the rural areas, however, coupled with continuing rural-urban migration, should lead to modest overall growth for pork products. Poultry demand, on the other hand, is much more dynamic. Because of high rural and urban income elasticities of demand, continued per capita income growth in excess of 5%/year is likely to generate substantial increases in demand. The relative price declines of pork and poultry products relative to the CPI, 19% and 29%respectively since 1996, will also stimulate demand.

Supply

Beginning in 1978, China started to reform her agricultural policies. One of the first steps was to encourage farmers to privately produce livestock products in addition to their work for the collective enterprise. As a result, meat production – primarily pork –increased very quickly. Most farmers bred 2-3 pigs, with some of these enterprises growing to 8-10 sows. At the time, they captured most of the available scale economies. More recently a number of super-sized, industrial pork producers have emerged – breeding hundreds of hogs. In contrast to pork, farmers in China had much more difficulty achieving scale economies with poultry – largely due to disease problems and management requirements. Therefore, growth in poultry production lagged behind pork until the last decade.

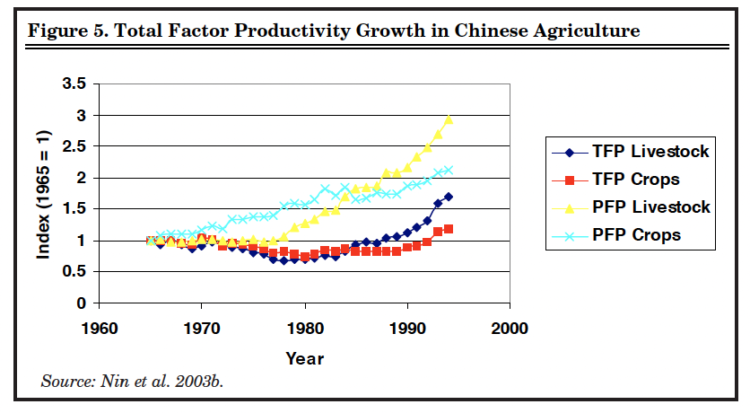

This evolution of China’s livestock industry from backyard production to commercial operations is evident from output per head of livestock in pork and poultry (Hertel, et al., 2000). This Partial Factor Productivity (PFP) measure shows a sharp rise in the pork sector during the 1978 reforms. However, the increase in poultry productivity did not occur until a decade later. Much of this productivity growth stems from additional feed and labor inputs. Total Factor Productivity (TFP) for China’s livestock sector (Nin, et al., 2003b), displayed in Figure 5, shows a more modest, but still substantial growth in livestock productivity since 1978. This growth exceeds the comparable world productivity growth rate for livestock by a factor of three over the 1964-95 period (Nin, et al., 2003b).

Figure 5. Total Factor Productivity Growth in Chinese Agriculture

Over the past decade, the entire Chinese economy has grown very rapidly. Livestock production, however, would expand relative to other sectors only if total factor productivity in livestock is higher than for other sectors. Comparable figures are not readily available for the non-agricultural sectors. Nonetheless, the rate of growth in live-stock productivity has been more than double that of crops. It is hardly a surprise that China has emerged as a net exporter of meats and a net importer of grains. Cheap labor in China’s processing stage of meat production provides further impetus to export growth for processed livestock products.

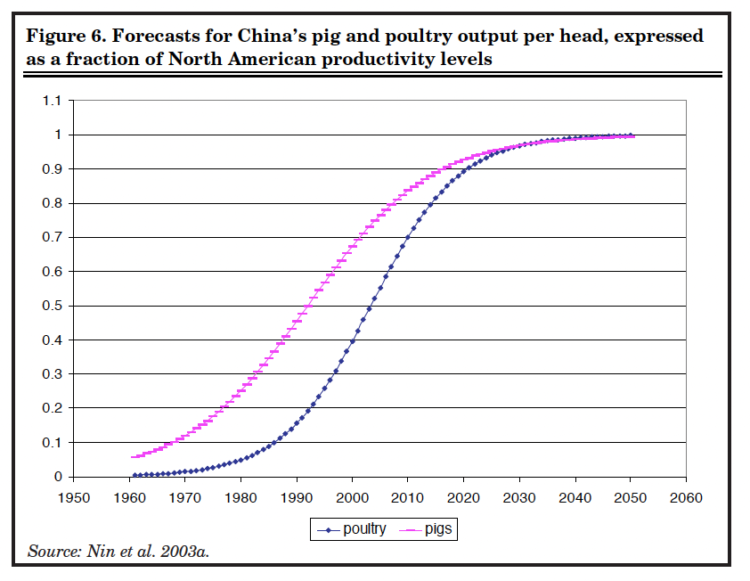

Much of the productivity growth in livestock has been fueled by producers’ “catching up” to modern technologies (Nin et al., 2003a). As producers approach best practice technologies, however, the scope for further productivity gains will diminish. Nin et al. (2003a) place China’s poultry output per head at about 40% of US levels, and 70% for hogs. Their estimated “catching up” curves in Figure 6 show a more rapid rate of convergence for poultry than for pigs. Their projections of pig production reach 90% of US productivity levels by 2015, with poultry reaching this level shortly thereafter. The supply-side story for poultry will be much more dynamic than that of pork in the coming decade.

Trade Policy

The third driver of China’s livestock trade is trade policy. Until the 1990’s, China’s meat tariffs were nearly prohibitive, with ad valorem rates frequently exceeding 100%. With China’s pending accession to the WTO, tariff rates in the 1990’s fell sharply, leading to a surge in reported imports. Meat imports into China are currently constrained by tariffs in 10 – 20 percent range. Under the WTO Accession Agreement, China established a tariff-only import regime for meats and dairy products, and all WTO-inconsistent non-tariff barriers are being removed. Foreign enterprises are permitted to engage in the full range of distribution services within China. This opens the way for significant increases in imports.

Figure 6. Forecasts for China’s pig and poultry output per head, expressed as a fraction of North American productivity levels

Future Scenarios

Based on the drivers of change identified above, we can consider the key forces underlying three alternative scenarios. Depending on the relative strength of each of these forces, the ultimate outcome may either be quite favorable to US exporters (Scenario 1) or it may favor Chinese exporters of meat products to East Asia (Scenario 3).

Scenario 1: China will be a major net-importer of meat products

Under this scenario, China defies the odds and capitalizes on WTO accession to dramatically reform the services sector (Mattoo, 2002). This reform would spur another round of rapid growth to 2010. In addition, an ambitious program of rural infrastructure investment, along with hukou reform and rural tax cuts would lift incomes in rural areas significantly faster than in the previous decade. In turn rural consumers would soon reach urban per capita pork consumption levels. Poultry consumption would increase even more rapidly due to the high rural income elasticity of demand for poultry meat.

On the supply-side of this scenario, exhaustion of the easy gains will slow productivity growth in pig and poultry production. Rapid growth in the rest of the economy also causes wages to rise, relative to the rest of the world, thereby eroding China’s comparative advantage in labor-intensive livestock production and meat processing. In addition, WTO accession may fail to fully open up the grains sector, due to opposition in a few poorer provinces hard hit by the demise of state-owned industries. Finally, tariff rate quotas and other tools for managed trade would allow China to check feed grain imports, further raising costs for livestock producers. In this environment, China becomes a net importer of meat products in the coming decade.

Scenario 2: China’s net imports will remain little changed over the coming decade

Under the status quo scenario China’s total livestock imports continue to increase at a modest rate mostly due to increases in skins for the leather and footwear industries, as well as by-products of meat processing in the USA and elsewhere (e.g., chicken feet). Imports of higher priced meat products are sluggish due to modest growth in domestic demand and the emergence of competing domestic suppliers – many affiliated with foreign firms. At the same time, exports of poultry products increase modestly, but disease problems prevent Chinese exporters from penetrating new markets. They continue to export primarily to Russia (canned meat products), Japan (de-boned meats) and Hong Kong (live animals). Sluggish growth in these economies constrains total export growth leaving net exports of livestock products at current levels over the coming decade.

Scenario 3: China will be a fierce competitor in Asian markets

This scenario relies in part on Maddison (1998) being right about China’s growth prospects. He has argued that future growth will likely be slower than during the 1978-1995 period, because China faces major problems in reforming state industry, fiscal and monetary policy. Increasing unemployment in the old industrial provinces of China prevent the reform of state-owned industries.

Poor performance of these industries, coupled with a half-hearted attempt to meet the WTO commitments in services reform sharply diminishes China’s overall growth rate and growth in demand for meat products.

Currently China’s uncompetitive primary production facilities are offset by a highly competitive meat processing activity which relies on the abundance of cheap labor in China. Under this scenario, China combines rapid productivity “catch-up” on the farm, with continued cost advantages in processing to become a fierce competitor in all livestock markets, particularly for highly processed products. Adding favorable impacts of recent investments in disease control and health standards yield a potential boom in processed meat exports from China. De-boned chicken is now shipped throughout Asia, and US exporters compete head-to-head with Chinese firms in many different markets. With imports stagnant due to modest demand growth, and high value exports surging, China finds itself with a much larger trade surplus in meat products in the year 2010.

Conclusions

Which of these scenarios is right? Only one thing is certain. The outcome of this footrace between supply and demand for meat products in the world’s largest economy will have important implications for producers around the world. Under-standing and monitoring the underlying drivers of change will be essential for those analyzing future developments in this market.

References

Beghin, J. and J. Fabiosa (2001). “China’s Accession to the WTO: Effects on US Pork and Poultry”, Iowa Ag Review, Center for Agriculture and Rural Development, Iowa State University, summer issue.

Delgado, C., M. Rosegrant, H. Steinfeld, S. Ehui, and C. Courbois. “Livestock to 2020: The

Next Food Revolution.” Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute, Food, Agriculture, and the Environment Discussion Paper No. 28, 1999.

FAOSTAT, Chinese language version, accessed in January 2003 at http://apps.fao.org/default-c.htm

Han, Yijun and Thomas W. Hertel (2003) “The Puzzling State of China’s Meat Trade”

Choices, forthcoming.

Hertel, Thomas W., Alejandro Nin, Allan Rae and Simeon Ehui (2000) “China: Future Customer or Competitor in Livestock Markets?” Choices , third quarter.

Li, Zhiqiang and Jimin Wang. “Forecast on the Development of China Meat Demand Market”, 1999.

Maddison, A., 1998. Chinese economic performance in the long run. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Paris.

Mattoo, A., 2002. “China’s Accession to the WTO: The Services Dimension”, mimeo, International Trade Division, The World Bank.

Nin, A., T.W. Hertel, K. Foster and A. Rae, 2003a. “Productivity Growth, Catching-up and Uncertainty in China’s Meat Trade”, forthcoming in Agricultural Economics.

Nin, A., T.C. Arndt, T.W. Hertel and P.V. Preckel, 2003b. “Bridging the Gap between Partial and Total Factor Productivity Measures using Directional Distance Functions”, American Journal of Agricultural Economics (forthcoming).

OECD, OECD Agricultural Outlook: 2000-2005, Paris: OECD, 2000.

Scmidhuber, J., 2001. “The Effects of WTO Accession on China’s Agriculture”, paper presented at a joint World Bank/MOFTEC workshop on China’s Agriculture and the WTO, Beijing, January 12 -13.