Agricultural Export Impacts of USMCA vs NAFTA plus Other Tariff Changes

December 19, 2019

PAER-2019-13

Maksym Chepeliev, Wally Tyner, and Dominique van der Mensbrugghe

A hallmark of the Trump Administration has been to reverse the post-World War II consensus on lowering of trade barriers and a commitment towards multilateral free trade, towards a more protectionist and perhaps mercantilist position vis-à-vis trade policy. One of the Administration’s first actions in this regard was the decision to leave the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, followed thereafter by raising tariffs on steel and aluminum imports. President Trump left no doubt where he stood on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which he often stated was the “worst trade deal maybe ever signed anywhere.” The administration’s actions on trade are likely to have significant implications for U.S. farmers as these actions target three of the largest markets for U.S. agricultural exports—Canada, China and Mexico—accounting for some 44% of U.S. agricultural exports representing an average of $63 billion from 2013 to 2015.

The purpose of this study is to estimate the impacts on U.S. agriculture of the recently agreed to United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). The USMCA—at times referred to as NAFTA 2.0— represents a renovated North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which has been in place for nearly 25 years. This analysis was done from two different perspectives. The first used the NAFTA agreement as the base case and compares it with USMCA to estimate the impacts of changes introduced in USMCA related to the agricultural sector, assuming no other changes. Because there have been many other changes in trade policy (e.g., steel and aluminum tariffs and the retaliation against those U.S. imposed tariffs), the second perspective includes two other cases reflecting other tariff changes. The first of these cases includes just the agricultural tariffs imposed by Canada and Mexico in retaliation of the U.S. actions in steel and aluminum. The second case adds agricultural tariffs imposed by other countries such, as China.

In addition, a literature study was done of what the impacts would be if NAFTA were to be eliminated without replacement by USMCA. In other words, what would happen if USMCA were not ratified and the Administration were to withdraw from NAFTA? The focus was on two credible studies, but these two studies use different assumptions in their analysis. The studies essentially assume that in the absence of NAFTA, tariffs in all three countries would return to most favored nation (MFN) rates. The results from the literature demonstrate that the U.S. economy and U.S. agriculture would face significant losses if NAFTA were eliminated without replacement.

NAFTA: An historical perspective

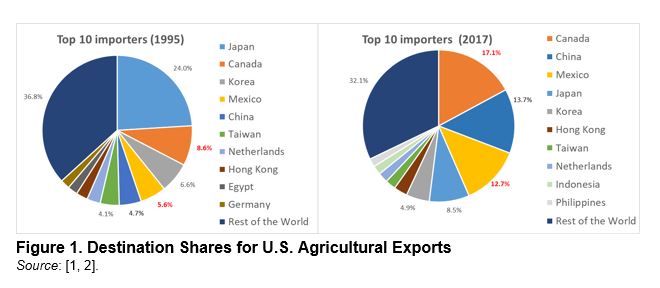

Figure 1 shows the shares of major agricultural export destinations in 1995 and 2017. Over that time period the shares of U.S. agricultural exports destined for Canada and Mexico more than doubled – moving from 14.2% to 29.8%. The other large change was China.

Figure 1. Destination Shares for U.S. Agricultural Exports

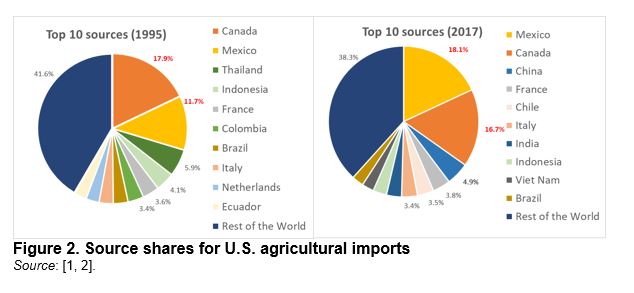

Figure 2 shows the sources of U.S. agricultural imports. Canada and Mexico were already the largest sources of U.S. agricultural imports in 1995. Their combined shares grew a bit from 30% to 35%. China was not an important agricultural exporter in 1995 but ranked third in 2017. It is interesting that while U.S. export shares to Canada and Mexico roughly doubled under NAFTA, U.S. import shares from those countries did not change much.

Figure 2. Source shares for U.S. major agricultural imports

Key policy changes in the USMCA

The most significant impacts of the USMCA related to market access are concentrated in the automobile sector and a few agricultural sectors:

- The domestic auto content for duty free access is raised to 75% from the existing 62.5%.

- 45% of the domestic auto content must be produced in factories where workers are paid at least $16/hour.

- Expanded import quotas in Canada for dairy and poultry products.

Many of the other new provisions relative to the original NAFTA deal with so-called ‘deeper’ integration issues such as reducing the impacts of non-tariff barriers, for example transparency in import and export licensing. There are also additional provisions that deal with intellectual property and the digital economy, the latter in its infancy when the original NAFTA was signed.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

U.S. agriculture has benefitted significantly from increasing market access in Canada and Mexico as a result of the formation of NAFTA some 25 years ago. The share of U.S. agricultural exports to these two countries has increased from 14.2% when the agreement was first signed to almost 30% currently.

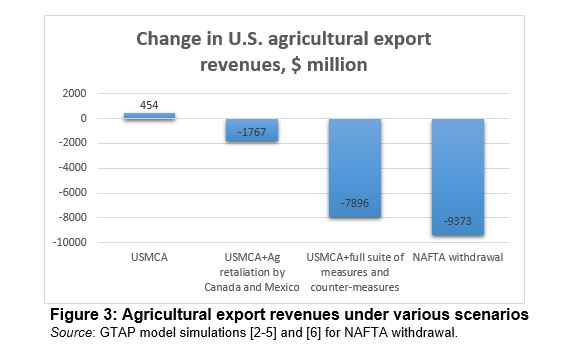

This policy brief provides four different perspectives on the new USMCA agreement (figure 3):

- First, it compares NAFTA with USMCA ignoring other trade policy changes that have been made. That analysis predicts a $454 million increase in U.S. net agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico concentrated in the dairy and poultry sectors.

- The second perspective adds the steel and aluminum tariffs the U.S. imposed on Canada and Mexico and the retaliatory tariffs imposed by Canada and Mexico. That analysis shows a net loss in U.S. agricultural exports of $1.8 billion.

- The third case includes all the other new U.S. tariffs and the retaliatory tariffs of other countries such as China. For this case, the loss in U.S. agricultural exports is about $7.9 billion.

- The conclusion from the final case is compiled from another study and represents an estimation of what would happen if NAFTA were to go away; e.g., Congress does not approve the USMCA and the President withdraws from NAFTA. The assumption is that tariffs in all three NAFTA countries would revert to most favored nation (MFN) status. The U.S. agricultural export loss in this case amounts to about $9.4 billion.

The new NAFTA agreement, USMCA, consolidates the agricultural market access gains from NAFTA 1.0—fortunately for farmers—and in some sectors leads to an improvement in market access—notably in dairy and poultry exports to Canada. However, the other cases represent significant losses for U.S. agriculture (figure 3).

Figure 3. Change in U.S. agricultural export revenues, $ million

A more comprehensive explanation of these findings can be found in GTAP Working Paper No. 84, “How U.S. Agriculture Will Fare Under the USMCA and Retaliatory Tariffs” by Chepeliev, Tyner and van der Mensbrugghe.

References

- United Nations. 2018. UN Comtrade Database. https://comtrade.un.org/

- Aguiar, A., Narayanan, B., and McDougall, R. 2016. “An Overview of the GTAP 9 Data Base.” Journal of Global Economic Analysis, 1(1):181-208. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21642/JGEA.010103AF.

- Corong, E., Hertel, T., McDougall, R., Tsigas, M., and van der Mensbrugghe, D. 2017. “The Standard GTAP Model, Version 7.” Journal of Global Economic Analysis, 2(1):1-119. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21642/JGEA.020101AF.

- Li, M. 2018. CARD Trade War Tariffs Database. https://www.card.iastate.edu/china/trade-war-data/. Accessed 19-Oct-2018.

- The Office of the United States Trade Representative. 2018. UNITED STATES–MEXICO–CANADA TRADE FACT SHEET Agriculture: Market Access and Dairy Outcomes of the USMC Agreement. https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/fact-sheets/2018/october/united-states%E2%80%93mexico%E2%80%93canada-trade-fact

- Ciuriak, D., Ciuriak, L., Dadkhah., A., and Xiao J. (2017). “Quantifying the Termination of NAFTA.” Working Paper, Ciuriak Consulting Inc. https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/Technical%20Paper.pdf. Accessed 24-Oct-2018.

- Chepeliev, M., W. Tyner and D. van der Mensbrugghe (2018). “How U.S. Agriculture Will Fare Under the USMCA and Retaliatory Tariffs.” GTAP Working Paper No. 84 and Farm Foundation, Center for Global Trade Analysis, Purdue University. https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/resources/res_display.asp?RecordID=5670