Crop Intensification vs. Production Of A New Crop To Raise Farm Income?

June 16, 1991

PAER-1991-8

S. A. Bruner, Agricultural Statistician, Alabama Agricultural Statistics Services; G.F. Patrick, Extension Economist and CL. Dobbins, Extension Economist

*Appreciation is expressed to Jim Simon, Howard Doster, and Chris Hurt for assistance and helpful comments at earlier stages of this project.

Many midwestern farmers encountered financial difficulties in the 1980s because of high interest rates, sharp reductions in crop returns, and the decline in land values. This led farmers to explore ways of increasing profitability. Additional uncertainties related to weather and prices (the droughts of 1983 and 1988) have also focused farmers’ attention on the variability of production and income. Interactions of price and yield variability with the debt level of the farm are important determinants of financial progress or vulnerability of the farm.

Two common methods of increasing crop returns are: 1) more intensive production of current crops, and 2) diversification into the production of alternative crops. In the sandy soils of northern Indiana, irrigation provides one method of intensifying com production and has the additional benefit of decreasing yield variability. Contract production of cucumbers for processing is an alternative crop with possibilities in the area because of the closeness of processing plants.

What is the potential of irrigated com and processing cucumber production on northern Indiana farms? Specifically, 1) how is the level and variability of net farm income affected by irrigated com and processing cucumbers? 2) how do the investments necessary for these activities affect cash flow, net worth accumulation, and the probability of survival? and 3) how does the level of debt affect these alternatives?

Procedures

A whole-farm simulation model was used to analyze the effects of irrigated com and cucumber production alternatives on a representative northern Indiana farm. The model accounts for annual production expenses, borrowing, debt repayment, cash flow, replacement of machinery and equipment, family living expenditures, and federal income taxes over a 10-year planning period. Each production alternative was simulated for a 10-year period with 50 replications. This allowed information about both the average value and variability of economic variables to be obtained. Each alternative was simulated under two debt levels for the farm to assess the interactions between yield and price variability and the level of debt.

Yield and Price Levels

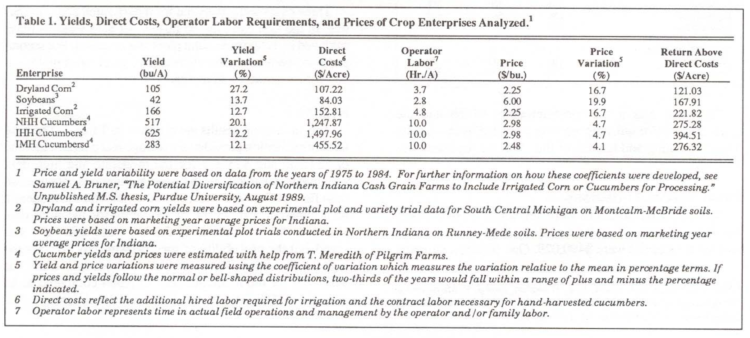

Table 1 summarizes the yield, direct costs, operator labor requirements, and price data used in the model. Both the average levels of prices and yields and the distribution of outcomes about these averages were used in the analysis. Since weather outcomes have such a major impact on yields, the correlation among yields was also included in the analysis. The correlation measures the degree to which yields move together. For this research, there was a positive correlation between the yields of all crops except for cucumbers. For cucumbers, there was a negative correlation. This means that an increase in com or soybean yield is associated with a decrease in cucumber yield. Since cucumber yields move in a direction opposite the other crops, this makes them a good crop Lo use in trying to stabilize income fluctuations.

Table l. Yields, Direct Costs, Operator Labor Requirements, and Prices of Crop Enterprises Analyzed.

By using com planting and cultivating equipment, non-irrigated hand-harvested cucumbers (NHH) could be produced with no additional investment in machinery or equipment. In addition to investments in irrigation equipment and wells, irrigated cucumbers which are hand-harvested (IHH) or machine-harvested (IMH) would involve the use of a $10,000 precision air planter to obtain the proper seed placement at the higher required populations. A used harvester costing $11,000 would be necessary for the mechanically-harvested cucumbers (IMH).

The irrigation system for cucumbers and com was assumed to be a 160-acre high-pressure center-pivot irrigation system which will actually irrigate 132 acres. The system had an estimated installation cost of $34,000 for the pivot, $32,000 for two wells and pumps, and $9,000 for a diesel engine. Annual ownership costs would be about 16% of the system’s cost or $12,000 (P.R. Robbins, E.E. Carson, R. Z. Wheaton, and J. V. Mannering, “Irrigation of Field Crops in Indiana,” Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service, ID-119, 1977).

Using average yields and prices, irrigated com and the cucumber alternatives provide a larger return above direct costs than either dryland com or soybeans. The reductions in yield variability for the irrigated crops and the price variability of contract cucumbers indicate that returns might not only be higher but also more stable.

Representative Farm

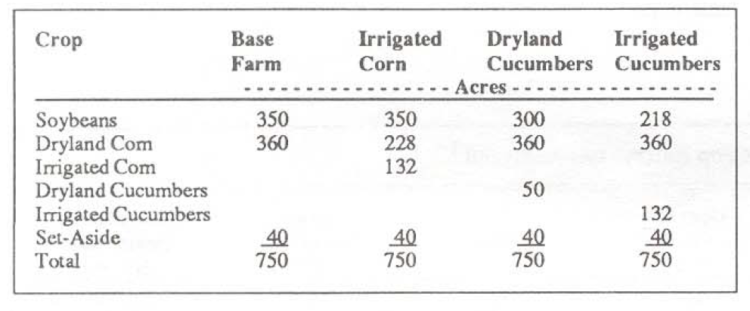

The representative farm situation was a northern Indiana farm of 750 tillable acres, 300 acres of owned land, and 450 acres leased under a customary 50-50 share arrangement. For the base farm situation, corn and soybeans were assumed to be grown in rotation. The soil types are Montcalm-McBride and Runney-Mede. Montcalm-McBride is a light sandy loam which is well-drained soil with thin bands of finer soil in the substructure and suitable for irrigation. Runney-Mede is a soil with a sand substructure, high in organic matter and poorly drained. The crop acreage for the base and other alternatives were as follows:

The farm was a sole proprietorship which had the equivalent of two full-time workers provided by the family. Timely planting and harvest of the com and soybeans was assumed.

Initial Financial Positions

Two financial situations were developed. In both cases, the value of owned cropland and buildings was $344,500 and the total assets were $490,029. One financial situation represents a moderate debt position with a debt-to-asset ratio of 0.37. Total debt was divided between $131,000 in real estate debt and $50,000 in intermediate term debt and accrued liabilities. The second financial situation represents a high debt position with a debt-to-asset ratio of 0.66. Total debts for this situation were divided between $240,000 in real estate debt and $81,000 in intermediate debt and accrued liabilities.

Because of differences in financial strength, the farms faced different borrowing restrictions. Interest rates for operating funds and intermediate assets were 10.25% and 11%, respectively, for the farm in the moderate debt position. The high debt farm faced interest rates of 11% for operating loans and 13% on intermediate assets. Refinancing was permitted, but neither farm could sell land to remain solvent.

The additional investments necessary for com irrigation and cucumber production were financed as intermediate term debt for farms in both financial positions. For the moderate debt situation, the 0.37 debt-to-asset ratio increased to 0.45 with irrigation and to 0.47 with irrigation and mechanical cucumber harvesting. For the high debt situation, the debt-to-asset ratio increased from 0.66 to 0.71 with irrigation and to 0.72 with irrigation and mechanical cucumber harvesting.

Economic Scenario

Asset values and production costs were assumed to increase at a 4% rate of inflation. It was assumed that an agricultural policy with set-asides, target prices, and deficiency payments similar to the 1988 feedgrain and wheat program would continue with the farmer participating. For a farmer with irrigated com, the ASCS com yield base for deficiency payments would be the same as dry land com.

Initial average com and soybean prices were assumed to be $2.25 and $6.00 per bushel, respectively. The initial target price for com was $2.84 per bushel. The mean prices for com and soybeans, as well as the target prices for com, increased at the 4% rate of inflation.

Three cases were analyzed for the irrigated com alternative. In the first case, the 60 bushel per acre yield increase achieved in the experimental plots was assumed. For second and third com irrigation alternatives, yield gains of 45 and 30 bushels per acres were assumed.

Results

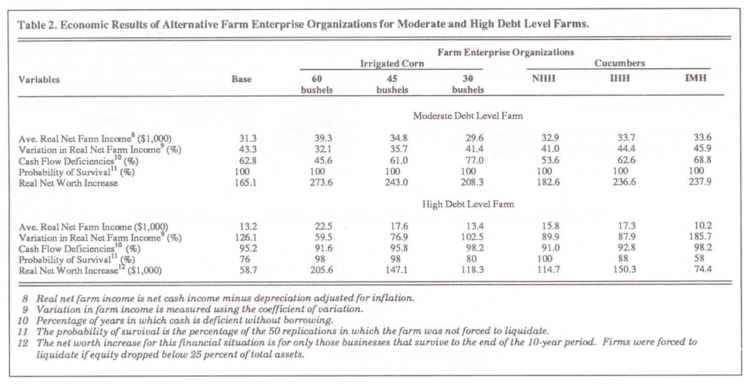

The simulation results are reported in Table 2. The base farm organization provided an average real net farm income of $31,300 and $13,200 for the moderate and high debt situation respectively. Both financial situations encountered cash flow difficulties – 62.8% of the years for the moderate debt situation and 95.2% of the years for the high debt situation. All replications of the moderate debt farm survived, but the probability of survival was only 76% for the high debt situation. The average real net worth increase was $165,100 for the moderate debt situation compared to an average of $58,700 for the high debt level farms which remained solvent (only 76% of these farms survived to the end of the 10-year period).

Table 2. Economic Results of Alternative Farm Enterprise Organizations for Moderate and High Debt Level Farms

Introduction of irrigated com with either 60 or 45 bushel yield increases resulted in substantial increases in average real net farm income and reductions in income variability relative to the base organization. However, the percentage of years with cash flow deficiencies changed only slightly with the 45-bushel increase. The probability of survival in the high debt situation increased from 76 to 98%. The real net worth increases were also substantially greater with 60 to 45 bushel yield increases from irrigated com than in the base case.

If only a 30-bushel per acre increase in average com yields resulted from irrigation, the economic results were less favorable. For the moderate debt situation, average real net farm income was somewhat lower (about $1,700 less) than for the base case, indicating the increase in yield was not large enough to cover the increased debt and production costs associated with the irrigation alternative. The percentage of years with cash flow deficiencies was larger than the base case. For the high debt situation there was a very slight increase in average real farm income, about $200, and the variation in income was reduced. As with the moderate debt situation, the percentage of years with cash flow deficiencies was larger than the base case. For all irrigation alternatives, both financial situations had larger increases in real net worth for all irrigation alternatives other than the base case. These real net worth increases were greater for the high debt situation than for the moderate debt situation, illustrating the importance of managing income fluctuations when the farm business is in a highly-leveraged financial position.

The cucumber alternatives provided mixed results. For the moderate debt situation, all three cucumber alternatives resulted in a slight increase in average real net farm income relative to the base case. However, the variability of income was also slightly higher with irrigation. The percentage of years with cash flow deficiencies was lower for the hand harvest alternative (NHH), about the same for the irrigated hand harvest alternative (IHH), but higher than the base for the irrigated mechanical harvest alternative (IMH).

For the high debt situation both hand harvest alternatives, NHH and IHH, provided higher and less variable average incomes than the base organization. However, the irrigated mechanical harvest (IMH) alternative resulted in a lower and more variable average income than the base organization. The probability of survival in the high debt situation improved for both of the hand harvest alternatives relative to the base organization, but was sharply lower, only 58%, for the IMH alternative.

All cucumber alternatives provided increases in real net worth larger than the base organization for the moderate debt situation. The irrigated alternatives, IHH and IMH, had larger increases than the non irrigated alternative, NHH. This increase represents approximately the value of additional investment in the irrigation system. Although the cucumber alternatives resulted in larger net worth increases than for the base case, the increases were not as large as for the 60 and 45 bushel irrigated com situations.

Increases in average net worth of the high debt situation in Table 2 must be interpreted with caution. While all of the cucumber alternatives provided an increase in real net worth greater than the base case, only 58% of the cases remained solvent for the entire IO-year period for IMH cucumber alternative. The net worth change of all farms, including those forced to liquidate, would be substantially lower. Both NHH and IHH cucumbers provided a greater average net worth increase and higher probability of survival than the base case.

Summary

The results indicate the intensification of current crop production, irrigated com, provided a better alternative than diversification into cucumber production. While cucumber production generally did provide some increase in net farm income and reduction in cash flow deficiencies relative to the base organization, the improvements were less than could be achieved through irrigated com.

With irrigated com production, it is possible to have cropping alternatives which both increase average income and reduce income variability. If producers can expect to achieve irrigated com yields of 45 or 60 bushels more than dryland yields, net farm income can be increased, and the variability of income and frequency of cash flow deficiencies reduced for farms with moderate debt levels. However, the size of the yield increase is critical in determining whether investments in irrigation are profitable. If irrigated com yields are only 30 bushels per acre more than dryland com production, there is little or no increase in net farm income and the variability of net farm income is only slightly less. Because of the additional investment required for irrigation, cash flow deficiencies with a 30-bushel increase become more frequent.

The financial position of a farm had relatively little effect on the ranking of the irrigated com alternatives considered in this study, but the situation is considerably different with respect to cucumbers. For the moderate debt farm, the cucumber alternative with the largest average real income was IHH. However, the hand harvest alternative provided reduced income variability and frequency of cash flow deficiencies. For the high debt situation, the irrigated handharvested cucumbers continued to provide the largest income among the cucumber alternatives, but also provided the lowest income variability. If the farm were to go into cucumber production and is highly leveraged it would probably select NHH, the non irrigated hand-harvested alternative, because of the lower financial risk and higher probability of survival. The moderate debt farm, in contrast, would probably select one of the irrigated cucumber alternatives, either IHH or IMH. However, both of these irrigated cucumber alternatives involve lower and more variable real net farm income than some irrigated com alternatives.

The results of this study suggest that there are diversification alternatives for cash grain farmers in northern Indiana, but the more intensive production of existing crops is a better alternative. Yield increases obtained and financial position of farms are important factors in determining the most viable alternatives. Although not examined in detail, operational expertise and available labor could also have substantial impacts on alternatives selected.