How is the budget for Farm Bill 2023 determined?

February 21, 2023

PAER-2023-13

Roman Keeney, Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics

In a previous brief we outlined the legislative process for Farm Bill 2023 and marked the publication of a baseline spending estimate as the first milestone. News reports indicate that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) will publish its baseline estimate in mid-February.[1] Based on 2022’s farm bill baseline, the nutrition title is expected to cost more than $1 trillion over the coming ten years making SNAP and similar programs a key target for deficit reduction. Prior to examining the new spending forecast it is useful to review the CBO’s function in policy, how to interpret a baseline, and how these estimates are best used as a tool in policy-making.

What is the CBO?

The Congressional Budget Office is a non-partisan government office tasked with estimating future spending under a variety of scenarios. The office is a primary source of information and projections for Congress on federal spending and revenue collection The CBO serves Congress in many of the same functions as the executive branch’s OMB (Office of Management and Budget), providing legal interpretations about how laws will be implemented and ultimately impact the federal budget.

The most prominent function of CBO is to score prospective legislation for its impact on federal spending. The score is the estimated net change to the federal budget of legislation as compared to maintaining the status quo. This means the CBO must maintain the necessary data and forecast models for the US economy and regularly update those to provide current estimates for lawmakers. This updating of information is critical because any particular forecast is a “point in time” examination of the future of the economy taking into account all currently known information. The “point in time” caveat is important, because the economy is always in adjustment, sometimes in response to large unanticipated shocks that will overwhelm prevailing economic trends.

How are farm bill baselines used?

Every year, CBO updates its forecast of mandatory[2] spending that occurs due to programs included in the farm bill. This annual update resets the current farm bill baseline for the ensuing 10-year window by incorporating new information from events that were not in the previous year’s baseline. In table 1, CBO baseline estimates from 2018 to 2022 are given showing that total spending estimates increased significantly. These adjustments are affected by some program changes[3] but are primarily driven by worsening economic conditions.

Notably, the projected spending over 10 years on the nutrition title has increased by $430 billion since the farm bill passed in 2018. This accounts for nearly all the farm bill’s net spending increase (i.e. all other program spending changes balance out to zero). These increases represent a share of spending on nutrition that has increased from 76% percent to 84% since 2018 passage of the law.

Table 1. Budget estimates for 2018 Farm Bill programs, ten-year spending estimates

| 2018 Passage | 2021 CBO | 2022 CBO | |

| Billions | |||

| Total Spending | $867 | $1,033 | $1,295 |

| Spending by Title | |||

| Nutrition | $659 | $815 | $1,090 |

| Crop Insurance | $77 | $95 | $80 |

| Commodity Programs | $63 | $55 | $56 |

| Conservation | $58 | $59 | $59 |

Source: Author’s calculations from CRS’s 2022 Farm Bill Primer sheet

The example of nutrition spending in table 1 illustrates a key conflict in entitlement programs. The program rules are written with a specific objective of providing assistance to those in need which generates a projected spending amount. If the performance of the economy worsens, then more assistance to meet the well-being threshold is required and more households will qualify to participate. This drives up the cost of the program while adding to an increasing deficit in a poor economy. Thus, the goal of helping low-income households (or any target of an entitlement program) must be balanced against efforts to control deficit spending.

In addition to providing updated information on how program spending responds to economic events, the CBO baseline in a farm bill year typically serves as the target spending amount for replacement legislation (see PAER 2023-09). The information in table 2 reviews budget scores for the previous four farm bills, and includes details about the overarching budget situation being faced at the time of passage.

Table 2. Farm bill budget scores from 2002 to 2018 (10 year budget windows)

| Year | Budget score (10-year spending) |

| 2002 Farm Bill | +73 $billion – passed under budget surplus with 50% of the increase going to refit commodity programs |

| 2008 Farm Bill | Neutral – passed with PAYGO[4] rules, increased revenues (taxes and fees) to increase nutrition, conservation & disaster spending |

| 2014 Farm Bill | -17 $billion – passed following sequestration budget rules that has already reduced the baseline by 23 $billion |

| 2018 Farm Bill | Neutral – all increased spending areas were offset within the farm bill |

Notes: information is sourced from CRS Report R 41510.

The normal process for Congress is to require replacement law to be budget neutral. In 2002, the federal budget was in annual surplus and the Congressional agricultural committees were allowed to increase spending against the baseline. This is contrasted to the farm bill process begun in 2012 amid difficult budget negotiations intermingled with a number of political conflicts. After two years of extensions, the 2014 Farm Bill was passed with 17 billion dollars in projected budget savings over a ten-year horizon.

Once the 2023 Farm Bill baseline is published by the CBO, we will begin to get clues about the budget objectives attached to the legislation. The political dynamics of today most closely match those in place during debate for the 2014 Farm Bill. The economic situation matches that era as well with an economy languishing to recover from a major shock a few years prior. Those are two indicators that the budget for the next farm bill could be a proxy for the larger budget debate and some lawmakers may oppose any farm bill that doesn’t include significant spending cuts.

How useful is farm bill baseline information?

A farm bill baseline assumes all current mandatory spending items are administered in their current form for ten years. Any change to the law is modeled for its net effect on spending. This simple net change belies an incredibly complex modeling process that deals with numerous economic interactions and long run projections of very uncertain phenomena. The complexity makes CBO a frequent target of policy-makers – particularly when the score indicates increased spending and deficit growth.

The most obvious critique is to look backwards at some legislation (like the 2018 Farm Bill) and note that it had a neutral budget score but increased the deficit. This is a verifiably true statement that critically ignores the fact that a CBO score is always estimated under the assumption of no unforeseen changes. In the case of the 2018 Farm Bill there have been numerous economic events causing spending to increase. Unaccounted for future events aren’t the only source of error however. Any forecast model will become worse as the influence of recent trends diminish and there is significant statistical error in trying to model on-farm decisions even for very short-term forecasts.

Consider the information required in producing a title I commodity program estimate – the CBO needs information on:

- Future prices

- The response of national acreage and output to future prices

- Producers electing either the PLC or ARC program

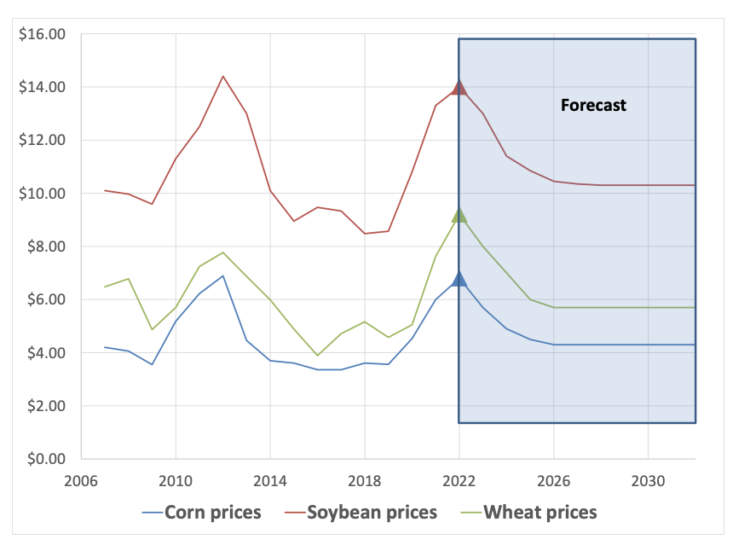

Future prices are unknown so that any modeled decisions that depend on the level of prices will carry forward that error. Additional errors will live in the estimation of producer decisions, particularly if the future decision-making process does not match that observed in historical data[5]. Figure 1 shows an example of crop prices forecast through 2032 and demonstrates a typical pattern. Specifically, we see that prices decline and eventually flatten for the out years of the period considered.

This is to be expected because the 2022 prices in the chart are well above average for the first twenty years of data, suggesting a “high price” period due to supply and demand factors. Moving forward, these high prices should tend to return to the long run price level. Because a forecast cannot incorporate future unknown shocks that may produce sustained high or low price eras, the best statistical prediction is merely that of a future with sustained stable prices.

Figure 1. Forecast price example

Continuing with figure 1, when the price diverges in 2027 to 2032 (as it will), the payments made from programs will be different from what is predicted. If the 2027 to 2032 average price isn’t close to the stable price prediction (i.e. high price and low price years offset one another) then government spending will be very different from the forecast. This calls into question the use of CBO baselines as absolute budget targets in the policy process as mandated by strict PAYGO adherence. The CBO baseline is a necessary tool in the process but these forecasts of spending must be put into context of the current state of the economy and how likely economic phenomena are to carry forward.

Concluding comments

This information in a CBO baseline is of great value but this information can be misused in the policy debate. Treating ten-year forecasts of spending as factual ignores the significant uncertainty in the dynamics of the economy. Strict adherence[6] to PAYGO rules may reinforce the treatment of uncertain spending predictions as determinative. The most important information emerging from the CBO forecast, particularly for legislation like the farm bill, is to understand how performance of the economy and other policies impacts its spending outcomes.

The 2018 farm bill experience is educational in this regard. Spending in title I has not been particularly large because programs are limited in their ability to address farm losses with increased subsidies. However, 2019-2021 all featured large transfers to farm producers in emergency spending in response to trade war shocks and COVID. The evidence of these payments indicates that the farm bill’s safety net didn’t match the expectations of policymakers. Budgetary restrictions based on estimated future spending are a partial cause of these limitations on the farm safety net.

The title I experience with the 2018 farm bill should be instructive when weighing the future of nutrition programs vis-à-vis their budget implications. Spending on nutrition is well above what was expected in 2018 due to shocks in the economy but SNAP and other programs were written to allow expansion as dictated by those shocks. The most important information in the CBO baseline for 2023’s farm bill will be how the spending in programs like SNAP has responded to economic shocks. It may be that spending has increased in ways that policymakers do not want, but it also could just be a signal that other areas of economic policy designed to promote growth and employment have fallen short.

The lesson of the two cases is clear from the perspective of reviewing the 2023 Farm Bill baseline or budgeting that legislation – the spending on entitlements in the farm bill will be largely determined by economic policies other than the farm bill. Pro-growth and employment efforts that keep the economy resilient to shocks will do more to control spending in the farm bill than any revisions or new restrictions aimed at limiting program spending as part of new law.

[1] This backgrounder on the CBO and budget process is being written prior to CBO’s 2023 Farm Bill baseline publication. We will review the Farm Bill baseline for 2023 in a subsequent article.

[2] Mandatory spending items are programs that include their own authorization for spending going forward. These are often referred to as entitlements because anyone that can prove they meet program definitions is entitled to the benefits of participation.

[3] There have been some COVID policy disbursements that are incorporated into the 2022 Farm Bill baseline.

[4] PAYGO is a House of Representatives rule that typically requires bills that receive floor votes to be budget neutral (or reduce the deficit). There is a separate PAYGO statute but it does not apply to individual floor bills; rather it is a restriction on increasing spending across all legislation as enacted across a session of Congress. An alternative to PAYGO called (CUTGO or cut as you go) is sometimes enacted as a rule for bills receiving vote on the House floor and requires that bills be budget neutral only through reduced spending (i.e. no revenue increase mechanisms can be used). See CRS R 41510 for full explanation on Congressional budget rules as well as statutory requirements on budget control.

[5] This is a version of the oft-cited Lucas critique.

[6] Note that PAYGO rules can be suspended (or laws can be waived) and often are when the budget priorities are seen as conflicting with the goals of a particular piece of legislation.