Live Hog Futures Lack Forecast Accuracy

June 16, 1991

PAER-1991-7

Author: Chris Hurt, Extension Economist and Martin Rice, Research Associate

Live hog futures have become an important part of the pork industry since their introduction in 1966. Futures markets have several important economic functions which help our market-based economic system operate more efficiently. First, futures markets are important collection points for information regarding supply and demand factors critical to price determination. Secondly, futures markets not only collect information, but also evaluate the anticipated price impacts from changing information on a day-by-day basis. Third, futures markets provide a mechanism to allow price risk to be transferred from those who want to reduce their risk to those who seek price risk for the chance of profits. Finally, futures markets are viewed by many as market-determined price forecast. This article will focus on the accuracy of live hog futures prices as a price forecast.

A Guide To Producers and Retailers

Observations of live hog futures prices are used in the industry in many ways to direct both production and consumption. It is clear that pork producers and pork wholesalers and retailers use futures market prices as a guide in some of their decisions. Producers’ observations of futures prices help guide production decisions. For example, when the June futures price is trading at a sharp premium to the May cash price, the producer can observe that the “best judgment” of the futures market is that prices will rise into the next month. In this situation, a producer may decide to keep hogs on feed somewhat longer to earn a potentially higher price in June. Producers also use futures price observations in their judgments about expansion or contraction of their herds. Live hog futures are traded for 12 to 14 months into the future. This period exceeds the approximately IO-month production period from breeding to market. Thus, high prices for futures 12 months in advance can stimulate production, while low prices can stimulate hog liquidation.

Retailers also use price signals sent from live hog futures. For example, retailers must plan meat features weeks or even months in advance. They attempt to feature meat products which are more moderately priced relative to other meat products during certain time periods. Their observations of futures prices help provide clues as to the market’s anticipation of which meat species will provide the best featuring opportunities at specific times.

Interestingly, most large producers and retailers use futures price observations in decision making, but many do not directly buy or sell futures; rather, they observe the price forecasting information provided by the market. Exactly how accurate are the live hog futures as a price forecast?

1980s Decade Tested

To test the forecast accuracy of Iive hog futures, we used all hog contracts which expired in the 1980s as a base. Thus, there were 10 years for each contract month. For example, during the decade, there were 10 February contracts, spanning the February 1980 contract through the February 1989 contract.

Futures traders attempt to anticipate the actual price of live hogs at the delivery point for the specific contract delivery month. Therefore, the average daily settlement price during the delivery month was used as the “correct” or final price. This final price was then compared to the average monthly settlement prices for each month prior to expiration. For example, if the February 1980 contract averaged $50 during the February expiration month, this was compared to an average price of say $48 for trading in January of 1980. In this example, the futures market had a -$2 error one month before expiration.

For each of the 10 years, these errors were computed for the 12-month period prior to expiration for each contract. Then, these monthly errors were averaged over the IO-year period. Two simple statistical measures are used to evaluate forecast accuracy: bias, and the standard deviation of the errors.

Downward Biased and Highly Inaccurate

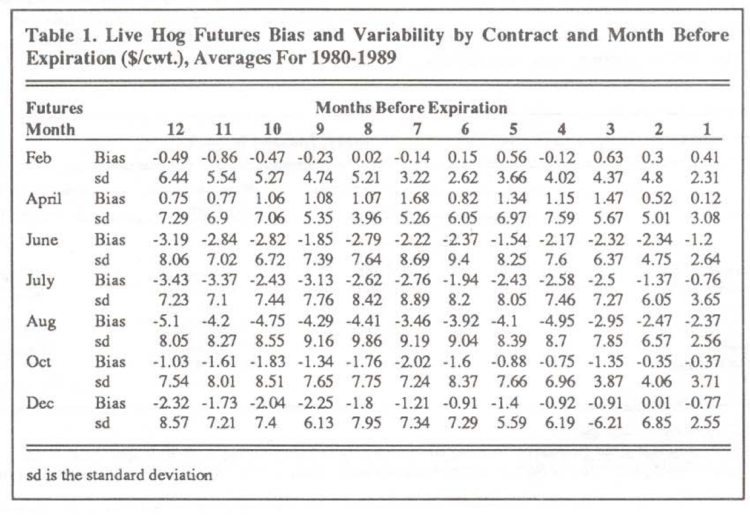

In general, live hog futures during the decade tended to be biased to the low side and not very accurate at forecasting the future. However, there were considerable differences by contract, and by the length of time prior to expiration. This evidence is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Live Hog Futures Bias and Variability by Contract and Month Before Expiration ($/cwt.), Averages For 1980-1989

For example, in the table, observe the February contract 10 months before expiration. The bias over the 10 contracts traded in the 1980s was a negative 47 cents per hundredweight. This means that, on average, in the month of April (10 months prior to February), the February futures averaged 4 7 cents lower than the final February price. This is a moderate downward bias. The standard deviation for this same example is $5.27 per hundredweight. This helps evaluate how badly the futures missed the final price, either on the high or the low side. For this particular month, the 10 yearly errors in dollars per hundredweight from 1980 to 1989 were as follows: +4.72, -2.55, +5.96, -5.10, -.94, +3.59, +3.88, -8.19, -7.88, and +1.86. For this group of numbers, there are five positive numbers when the market overpriced, and five negative numbers when the market underpriced. However, the underpriced errors tend to be larger than those of the overpriced years. This large underpricing in certain years is a characteristic related to hog futures. The large underpricings are generally in cycle high price years.

In a normal distribution, adding one standard deviation and subtracting one standard deviation provides about a two-thirds odds range. Applying this principle to the $5.27 standard deviation in the example suggests that about twothirds of the errors were between -$5.27 and +$5.27 per hundredweight. Alternatively, about one-sixth of the time the errors would have been greater than +$5.27, and onesixth of the time greater than -$5.27.

Some interesting observations regarding bias and forecast accuracy can be made from Table 1. The February and April contracts tended to have a positive bias of overpredicting the final futures price. The strongest positive bias was in the April contract with some months well over a dollar. However, the remaining contracts from June through December tended to have a negative bias, with the largest occurring in the June, July, and August contracts. August in particular had a downward bias which was as much as $5 per hundredweight. These are indeed very large downward biases that arc detrimental for producers who hedge.

Errors were also very large in the summer months. Standard deviations of $7 to $9 per hundredweight were common in the summer contracts. It is also important to note that both the bias and the errors tend to be smaller as the contract approaches maturity. This makes sense, as the knowledge about the ultimate “correct price” should be better one month before maturity than 12 months before. However, while errors tended to be moderate for one month before maturity, two months before maturity the errors were in the range of $4.06 to $6.85 per hundredweight.

Using Hog Futures In Decisions

The pork industry uses futures price observations in a number of key decisions as outlined in the introduction. One important implication of this information is that the historical evidence from the decade of the 1980s shows live hog futures prices to be downwardly biased on average, and to be more inaccurate in price forecasting than many people may have believed.

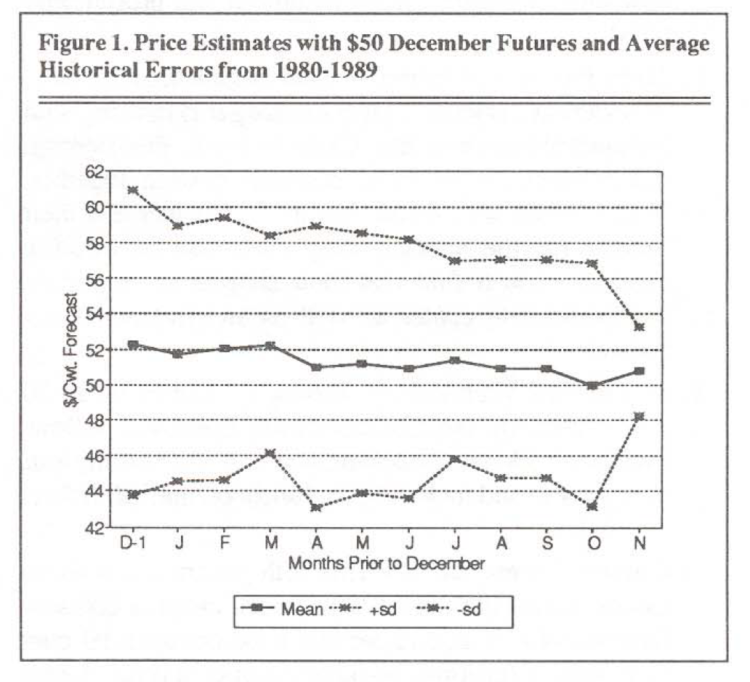

To illustrate this point, say that in March, the December futures price quote is $50 per hundredweight. How would a hog producer or other market participant bring information about the historical accuracy into their decision making? Will hog futures be $50 in December? How large a range around $50 should the decision maker consider? From Table 1, the bias of the December futures contract nine months prior is -$2.25, and the standard deviation is $6.13 per hundredweight. Because the bias shows that the futures market historically tended to underprice futures at this point, one could add the bias to the futures quote for a mean futures price of $52.25. To this adjusted price, the application of plus-and-minus one standard deviation provides a range of $46.12 to $58.38 as a roughly two-thirds chance of occurrence. Historical errors suggest there may still be one-third odds that the final futures price will be outside this range. This indeed is a wide range, but it is based upon historical errors.

An example of this application to a futures price quote is shown in Figure 1. For illustration, it is assumed that the December futures price remained at $50 for a 12-month period prior to expiration. The mean line in the figure adjusts for monthly bias, and the upper and lower lines reflect the plus-and-minus one standard deviation rule. The two-thirds odds price ranges are large. For the prior December, which is 12 months before maturity and shown as D-1, the range is from $43.75 to $60.89.

Conclusions

The live hog futures market tended to be downwardly biased and more inaccurate than many realized during the decade of the 1980s. The downward bias was greatest for contracts maturing in the summer, with the August contract bias reaching as much as -$5.10 per hundredweight. Generally, the longer the period prior to maturity, the greater the downward bias. Standard deviations of forecast errors for the live hog futures market were as low as a few dollars close to maturity, and as much as $9 per hundredweight for certain contracts and time periods.

When this historical accuracy of the futures market is projected to a current futures price quote, the price ranges are very wide. The implication is that while the futures market attempts to make an accurate forecast through the efforts of well-informed traders, no one is truly able to peer into the future and derive an accurate forecast. Therefore, producers and others in the pork industry who observe and use futures quotes in their decision making need to consider these inaccuracies, and certainly also include other types of information in their decision-making process.

While live hog futures have been shown historically to have sizeable inaccuracy, this does not necessarily mean they will have these same errors in the future. It is also important to remember that even if futures prices are not very accurate forecasts, they can still serve as a risk-shifting mechanism. In addition, while the futures have been shown to have difficulty accurately predicting prices, so do other market analysts, authors included.