Reforms on Private Polish Farms: Can the Five-Acre Family Farm Survive?

June 16, 1991

PAER-1991-9

Author: Jozef Kania, Agricultural Economist at The Agricultural University in Cracow, Poland and visiting professor at Purdue University in 1991

Polish agriculture is a mixture of large, socialized farms and small private family farms. In sharp contrast to other Eastern block countries, former governments were never able to fully collectivize Polish agriculture, even though the rest of the food system, including farm inputs and the food processing sector, was incorporated into central planning.

In Poland, agriculture employs about 28% of the labor force and over 40% of the population reside in the rural countryside. Nearly 60% of Poland’s land is agricultural.

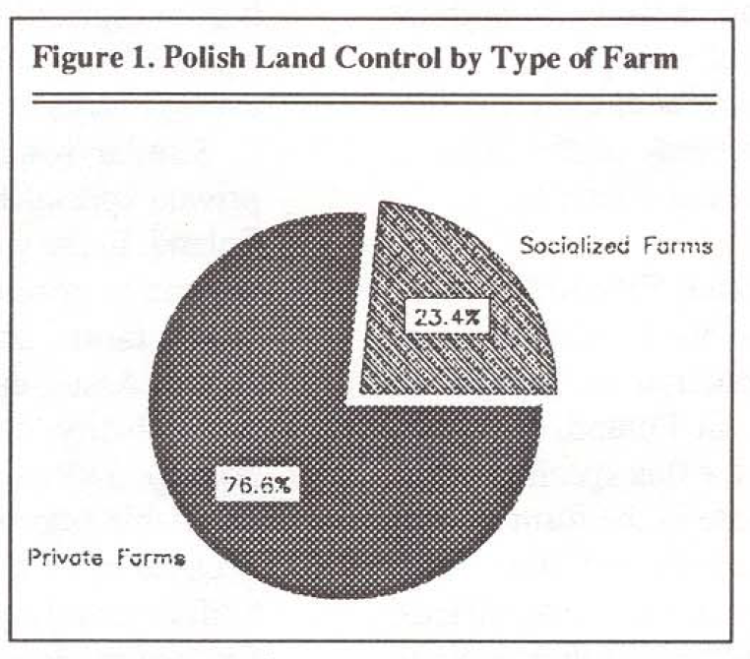

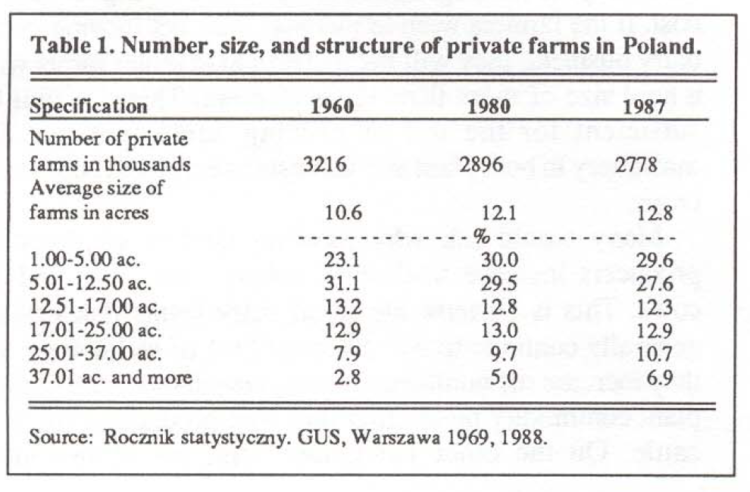

Private farms operate 76.6% of the agricultural land. The remaining 23.4% is in socialized farms. (See Figure 1.) The average size of the 2.8 million privately owned farms in 1987 was only 12.8 acres. Over half were 12.5 acres or smaller. In the last 30 years, we received much critic ism from economists because of our farm structure. Table 1 shows an increase of the smallest farms and the largest farms. For example, farms that were one to five acres increased from about 23% of all farms in 1960, to nearly 30% in 1987. Farms that were over 37 acres in size represented about 3% of all farms in 1960 but increased to about 7% in 1987. It is interesting to note that the largest farms still represent less than 10% of all farms, but they control about one-fourth of the agricultural land. Facilitating this consolidation into more efficient sizes of farms will be a primary focus of future agricultural policy.

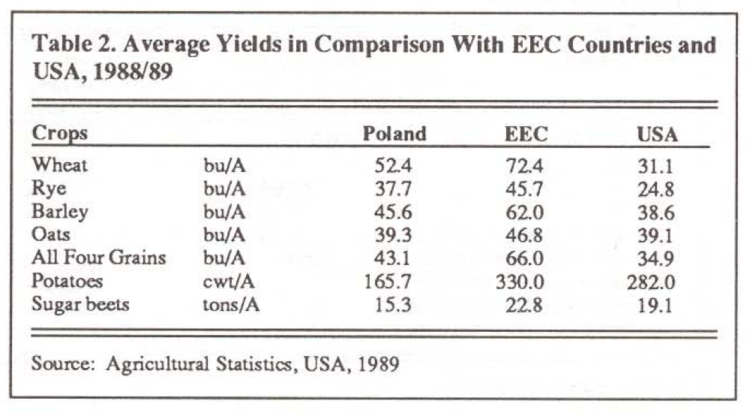

Private farms supplied about 85% of total agricultural production. The principal crops and their percentage of cultivated land are: rye 20%; wheat 14.8%; potatoes 13.4%; fodder beets 9.8%; barley 8.7%; oats 5.9%; and sugar beets 2.9%. Average yields were poor compared to Western Europe because of infertile soil, insufficient use of fertilizer, and inadequate mechanization. Table 2 compares average yields for Poland, the EEC, and the United States. There were 855,000 tractors in 1985 in Poland, of which 667,000 were owned by private farmers. Most of these tractors were purchased used from the socialized farms. This inventory represents an average of one tractor for four private farms. Poland has become an importer of grains instead of an exporter, particularly wheat. Imports of wheat and com amounted to 6.9 million tons in 1980, but shortages of foreign exchange since have limited imports to about 2 million tons annually. Polish agriculture produces very little high-protein feed supplements. Thus, livestock feed efficiency is poor. Because of the short growing season, we have little production of com, and no commercial soybean production. Production of rapeseed, whose protein meal is suitable for livestock, is expanding. We have some production of com cob mix, which uses the plant and the immature ear as a protein source, but this too is limited by a shortage of appropriate grinding machines.

Former governments encouraged the development of livestock production through increased fodder supply from the state monopolies, through improvement in breeding stock, and through partial tax relief for raising hogs. Emphasis has been placed on producing both hogs and sheep.

Milk Production on Private Farms

Milk production on private farms is the least developed and the most extensive livestock enterprise in Poland. In total production, Poland ranks fifth in the world, but yield per cow ranks twenty-third in the world. Production is also very seasonal. For example, milk production in the winter is 52.2 million pounds per day, but in the summertime daily production is 95.4 million pounds.

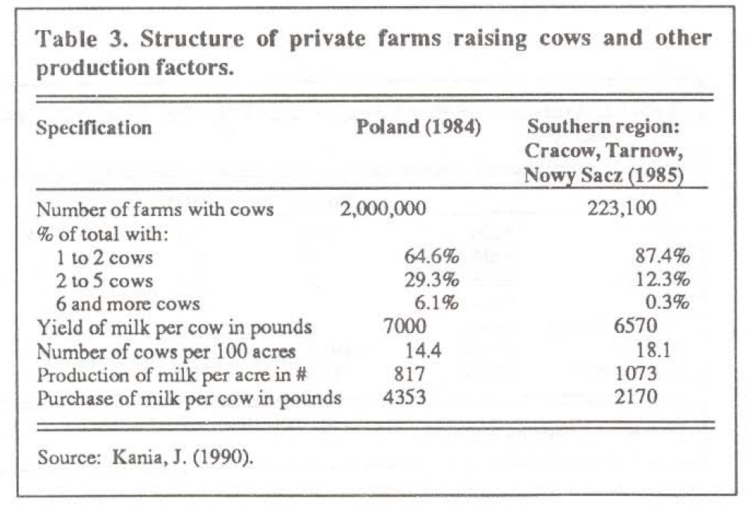

In Poland, private farms raising cows tend to be very small, especially in the Southern region. The Southern region is much different than other areas of Poland. Farms there have an average size of under 7.5 acres. Additional characteristics of the Southern region are: more part-time farming, a smaller degree of mechanization, a smaller scale of livestock production, smaller mixed livestock buildings, a higher percentage of pasture, and a large population of residents and tourists.

Approximately two million farms in Poland were raising cows in 1984. On these farms, about 65% had either one or two cows, and 29% had two to five cows. See Table 3. In the Southern region, 87% of the farms had either one or two cows. Farms with six or more cows represented only 6% of the entire country’s farms, but less than 1 % of the farms in the Southern region. In addition to small farms, there is a lack of milk marketing and processing capacity throughout the country. As an example, only 2% of milk producers and 40% of local dairy stations have equipment to refrigerate milk. These numbers reflect the magnitude of the problem in milk production and processing for our country.

Intensified Livestock Farms: More Efficient

In the late 1970’s, a movement towards specialization and concentration of livestock production took place on private as well as socialized farms in Poland. New and remodeled structures were the basis for this specialization. This process was supported by the state in the form of debt capital with very low interest rates, with building plans, material allotments, and help from local extension offices. Farmers received tax credits if they increased their amount of agricultural land and production. This process, of course, was controlled by the state, so farmers were afraid to build large new buildings or buy too much land because of the general government goal to socialize more private farms at that time. During the mid-to-late ’70s, construction was completed on approximately 100,000 specialized buildings for cattle, hogs, sheep, and poultry.

The National Institute of Agricultural Economics in Warsaw and our University Department of Agricultural Economics in the Southern region investigated this intensification process. Our goal was to evaluate the future prospects for these specialized farms from a social and economic prospective.

Economic results clearly show there is a distinct advantage for the specialized private farms compared to average private farms. As a whole, total inputs per unit of production for specialized farms compared to private farms were: 56.6% for dairy cattle; 66.5% for beef feeders; 51.4 % for sheep; and 56% for swine farms. It appears that net output per work day is from 2.0 to 3.1 times higher than the average for private farms in Poland.

The advantage realized by specialized farms over total private farms in labor productivity is a result of higher efficiency of inputs, higher volume of production, higher crop yields, and lower labor requirements. Net worth of specialized farms was also two times higher than for average farms.

Individual effects of specialization were expressed in higher agricultural income per person. Social effects included higher net final production per acre and lower than average costs of agricultural products.

Similar results were reached in our investigation on private specialized farms in a specific Southern region of Poland. In the years 1976 to 1988, we observed much better economic results on specialized than on the traditional mixed farms, and also much better than on the socialized farms. Assuming dairy returns had an index of 100, the profitability of specialized livestock enterprises was: poultry 350%; hogs 225%; and sheep 180%. The least profitable enterprise of livestock production was dairy cattle because of relatively low price ratios, very high costs of buildings and equipment, and higher costs of mechanization for feed production.

Perhaps surprisingly to many Americans, the highest incomes were from the smallest farms with three to five cows and from the largest farms with 12 to 15 cows. Both of these groups of farms require high levels of inputs. The small farms require large amounts of labor. The opportunity value of labor to move into other jobs is low, thus returns are favorable for working with the small herds. The larger farms, which had 12 to 15 cows, employ much more capital. While debt capital has relatively high interest rates, the larger sized farm was able to gain substantially greater production efficiencies. Thus the increase in production efficiency for the larger sized farms offset the higher capital cost. If the farmers wish to increase their net income in the dairy business, they will need to organize larger farms with a herd size of more than 12 to 15 cows. This size will be sufficient for the use of milking equipment and for machinery to both plant and harvest the required fodder feed crops.

Many would ask why incomes tend to go down as producers increase herd size between five cows and 12 cows. This is because the small dairy farms that expand generally continue to use the same type of technology. As they increase the numbers of cows, they divert more of their plant commodity production into feed production for their cattle. On the other hand, they tend not to use more machinery and milking equipment that help larger farms make their use of labor more efficient. Consequently, they lower their total income because of the reduction in vegetable crops and other crops produced, but do not gain the efficiencies of production from the larger sized dairies.

Unfortunately, milk production does not provide very profitable returns, and intensification of many farms would require large amounts of capital. Therefore we must take into consideration these low returns and high capital inputs as we reform the dairy production sector.

The final output per acre in the private sector is increasing at the rate of about 2% each year. With this rate of increase, we expect the average private farm to reach the production level of the specialized farms in the year 1999.

Part-time Farms are Important

In Poland, there are a great number of farms of mixed income sources, called either part-time farms or peasantworker farms. Thus, besides large economically efficient farms, there are small farms of low production capacity which supplement their income from farming with earnings from off-farm work.

Part-time farming is a subject of severe criticism based on the belief that part-time farms are characterized by a low level of production. However, the results of recent research show that the agricultural production level is not always low on such farms. Many believe that the owner of a part-time farm would be overburdened with work and would be unable to work efficiently either on his farm or in his off-farm job. This opinion has not been confirmed by our research. It appears that owners of part-time farms are efficient workers both on and off-farm.

In 1980, 27.5% of the farm operators were engaged in permanent work off the farm. These farmers are concentrated mostly in the Southern section of Poland. Future agricultural policy should not be indifferent to this group of farmers but should introduce economic mechanisms which would activate the entire production potential of these farms, including a better use of their labor resources.

How can we better utilize their labor? Keep in mind the need for our agriculture to have structural changes which will move us to larger farms. If we do not want these changes to be more difficult and expensive in the future, we must now encourage some part-time farmers to switch to a production system which would utilize the existing labor resources in full on their farm, but yet would not require costly investments.

There are two ways available to make better use of the large labor resources on small part-time farms. One is an intensification of agricultural production. Examples of intensification would include: greater quantities of commercial concentrated fertilizers, improved seed varieties, and increased use of agricultural chemicals. The lager private farms, mechanized co-ops, or collective farms could help them with machinery services. The new processing and cold storage plants could provide incentives for the small farms, and the whole region’s specialization in very labor-intensive products such as: strawberries, wild strawberries, black and white currants, raspberries, gooseberries, and green peas. Such efforts would increase production for the market as well as increase the incomes of small farms. For many years most fresh vegetables on the agricultural free market came straight from small, part-time farms located close to the cities.

The second way to increase labor productivity and incomes on part-time farms would be to encourage small farm owners to operate private workshops. These workshops would use the labor resource as well as local raw materials to produce products. Examples of these types of workshops might include production of small novelty items, production of topsoil products, forest products, and mushrooms. Since the marketing industry for many of these products is not developed, it would be the responsibility of governmentally organized industries to provide transportation of the raw materials to the rural areas, as well as transportation of the finished products into cities or to export destinations.

Because of the limited skills in marketing, the organization of these enterprises cannot rest with part-time farmers alone. A number of cooperatives as well as the food processing industry should be vitally involved. This certainly provides an important opportunity for foreign partners in joint ventures. Our experience to date for this kind of activity on small farms has produced positive effects. Efforts should be made to widen its scope and make it a common practice all over the country.

In my opinion, the future of Polish agriculture is tied with this type of movement toward commercial family farms. However, under present economic and political conditions, a speedy transfer of land from small to larger farms may not be feasible. Even in the long run, there should be a place for part-time farms which can complement the agricultural output of larger farms, and which in some regions can help the development of agriculture. Part-time farms should be seen as an opportunity to help develop the local economy in some regions.

Many Challenges Ahead

Polish people have taken pride in the fact that theirs was the only former Eastern Bloc country which saved private family farms. At present, a new democratic system of law and economics is being realized. However, movement to a market economy will be harsh for many Polish farmers because of necessary structural changes in the farm and marketing sectors. From my point of view, agricultural policy should not be focused on the whole agricultural sector, but rather on certain types of farms with good management and high production efficiency. In addition, we must begin to think more about enterprise specialization in areas where we can compete. Only economically efficient producers will survive in the new competitive conditions.

While the economic effects of specialized farms in Poland are positive, the social effects on farm families are also a concern. For many of these part-time farmers who are not able to gain the economics of size, it may be possible to intensify the use of their labor through special types of enterprises or workshops.

In the short term, Polish farmers can sharply improve total production if inputs are available. Those most needed include: high-protein feeds for livestock, fertilizers, crop chemicals, fuel, machinery and spare parts to enable farmers to produce more fruit, vegetables, potatoes, sugar beets, food grains, and feed grains to support further increases in livestock output. The second Borlaug Mission to Poland in August of 1989 concluded that “The genetic potential of the crop varieties and livestock breeds is high, but farmers now are achieving only 50 to 70% of the potential, and inadequate production inputs are one of the major limiting factors.”

In the long term, development of agriculture and the food system in my country must evolve with continued economic reforms in the general economy. Reform of the banking system and development of financial markets should create opportunities for farmers and other businesses to use debt capital, to make investments, and to begin modem farming and new ventures in agribusiness. We must develop a market for land, although none has previously existed. This will require new legal and regulatory systems to increase the size of farms by allowing consolidation of existing fields into larger sizes. We must increase both the volume of inputs and the availability of inputs – this is an immediate need. Growth and development of the marketing and food processing sectors are essential, and perhaps this will occur with Western joint ventures. We must create efficient private farm production systems and use private Western agribusiness technology and capital. Our research and educational specialists need to travel abroad to study farm management and food marketing, as I now have the opportunity to do at Purdue University. Finally, we need to revitalize the extension service for the enormous educational task ahead of us.

REFERENCES

Grochowski, Z., Kazmierczak, M. (1985), Tendencje zmian w gospodarstwach specjalistycznych, l,agadn. Ek.on. Roln. no I and 2.

Kania, J. (1985), Ocena ek.onomicznej efeklywnosci inwestycji inwentarsk.ich w indywdualnych gospodarstwach specjalistycznych poludniowej Polski, Wies i Rolnictwo, no 3148, PAN IRWiR.

Kania, J. (1990), Organizacyjno-ekonomiczne aspekty rozwoju gospodarstwspecjalizujacychsie w chowie bydla, NoweRolnictwo, no 1/2/3.

Kania,J.,Szaro, L. (1990),Koszty inwestowania i efeldywnosc gospodarstw indywidualnych w zaleznosci od wielk.osci stada krow, Informator Regionalny ZUP no 291, Akademia Rolnicza w Krakowie.

KJodzinski, M. (I 983), Part-lime farming in Polish agriculture, Oxford Agrarian Studies, vol. XII.

Penn, J.B. (1989), Poland’s Agriculture-It Could Make the Critical Difference, Choices, fourth quarter.

Rocmik statystyczny (1986), GUS Warszawa.