Retail Food Price Outlook

December 9, 2020

PAER-2020-24

Author: Jayson L. Lusk, Department Head and Distinguished Professor of Agricultural Economics

Grocery food prices rose markedly in the aftermath of the onset of COVID-19. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, retail grocery prices spiked 2.6% from March to April 2020; this was the largest monthly change in the food at home consumer price index since the high inflation of the 1970s. COVID-related disruptions led to a run on grocery stores as consumers avoided restaurants and sought to stock up and fill pantries and freezers. In the third week of March 2020, consumer spending at groceries was a whopping 68% higher than at the first of the year. All that extra demand at grocery pulled up prices. Then, in April and May, shutdowns and slowdowns in beef and pork processing due to worker illnesses reduced the supply of meat products available, leading to a significant price increase for beef and pork.

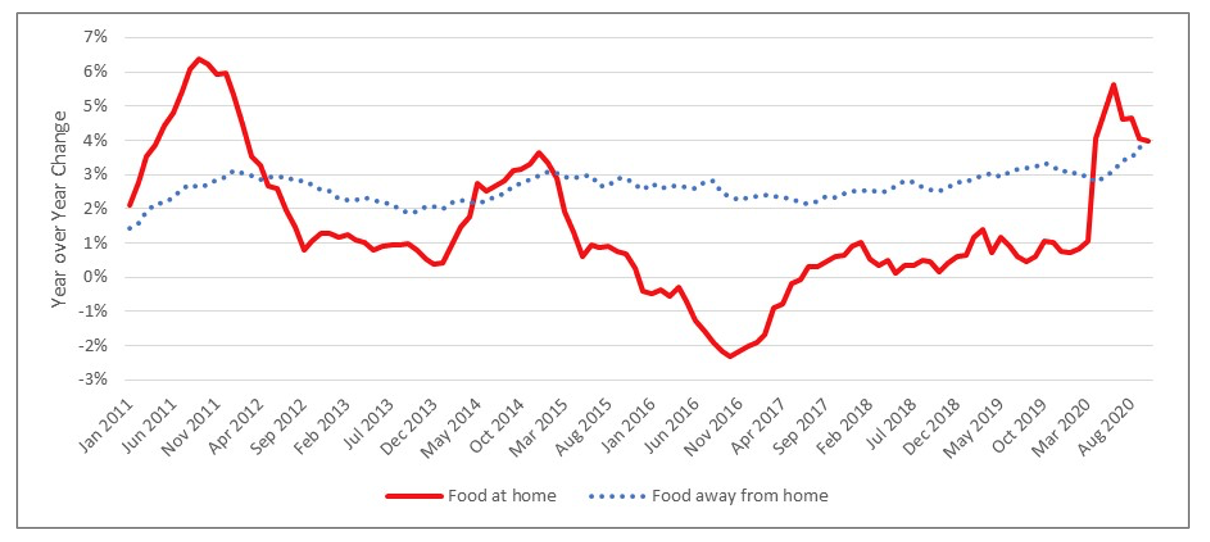

While many of the food prices have come back down off the spikes in late spring and early summer, it remains the case that retail food prices are significantly higher now than at the same time last year. In October (the last data available), prices of food at grocery were 4% higher than the same time last year. It’s been almost a decade, since 2011, that we observed this rate of annual food price inflation. Despite the restrictions on eating out, the price of food away from home is 3.9% higher in October 2020 than in October 2019; this year-over-year change is higher than has been observed in at least a decade.

These year-over-year increases are significantly higher than the what has typically been experienced. From 2000 to 2019, the average annual change in retail grocery prices was about 1.9%. In fact, throughout much of 2015 and 2016, retail grocery prices actually fell relative to the year prior.

Figure 1. Year over Year Changes in Monthly Food Prices

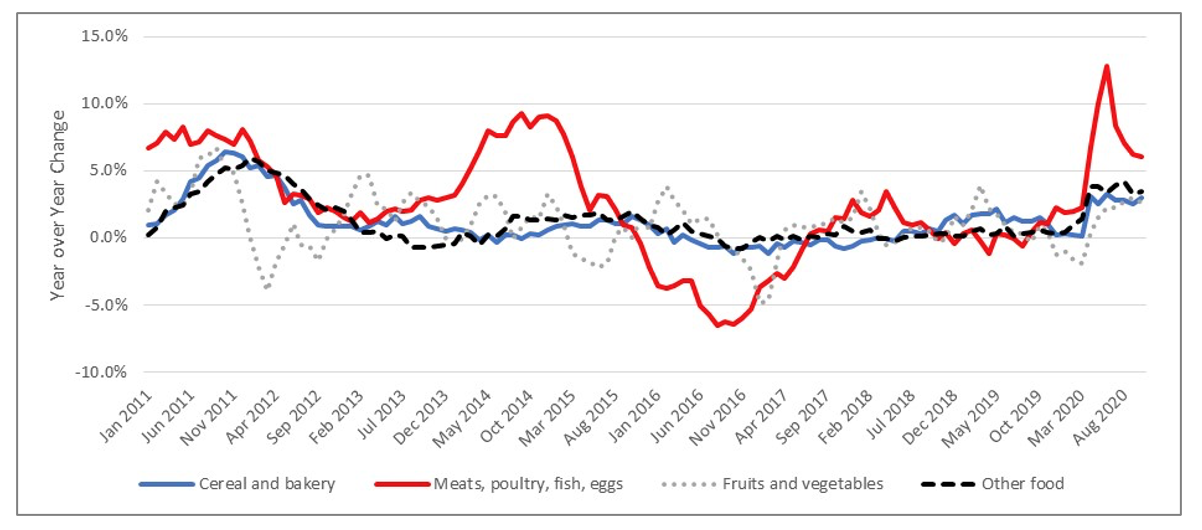

Fluctuations in meat, dairy, and egg prices have been the biggest drivers of the overall food price hike. In June 2020, prices of these products at grocery were 12.8% higher than the same time in 2019; as of October 2020, prices of these products are still running 6.1% higher than in 2019. However, the price increases are not just limited to meat and animal products. Cereal and bakery product prices are 3% higher in October 2020 compared to October 2019; Fruit and vegetable prices are 2.6% higher in October 2020 than in 2019.

Figure 2. Year over Year Changes in Monthly Prices of Four Grocery Categories

There is good reason to believe that food price inflation is even higher than what is reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Many products were stocked out and groceries limited the amount consumers could buy (e.g., two packages of ground beef per customer). In these cases, the real price experienced by the customer are much higher than the sticker-price (one might say the price of a stocked out item is infinitely high). Moreover, the BLS explained that prior to COVID-19, most price data were collected in-person, but when they moved to online data collection to protect their workers, they had to dramatically reduce the volume of price data being collected. As a result, there were many items, such as the prices of turkey prior to Thanksgiving, for which not data were reported.

Looking ahead to 2021, the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Economic Research Service is projecting a return to more modest levels of food inflation. For food at home, they project a 1% to 2% increase in prices (the 20 year historical average is 2.8%), and for food away from home, the projection is 2% to 3% (the 20 year historical average is 2.3%).

These projections seem to suggest an anticipation of a return to normal. However, we are not totally out of the woods. As of the first of November 2020, consumer spending at grocery remains 11% higher and restaurant and hotel spending 30% lower than the first of 2019.

Even if food price inflation reverts to historical norms, this just means that prices have stopped increasing as fast as in 2020. Price levels remain higher than they were previously. As such, it will be important to keep an eye on food affordability and measures of food insecurity in 2021.