Trade and trade policy outlook, 2022

January 13, 2022

PAER-2022-3

Author: Russell Hillberry, Professor of Agricultural Economics

Last year’s trade policy outlook offered informed speculation about the trade policy that might be expected from President-elect Biden (Hillberry 2020). At that time, the incoming administration seemed to be attempting to maintain ambiguity on many trade issues, so there was considerable uncertainty about how a Biden administration might handle trade policy. One year later, the administration’s approach is becoming clearer. US trade policy will not be as outwardly combative as it was under the Trump Administration, but neither should we expect a return to the pre-2016 situation. This has implications for the supply chain crisis, and for the broader international trade system, which is important for export-oriented agriculture.

The Supply Chain

One of the economic concepts with which many people have recently become familiar is the “supply chain” – the sequence of production and transportation activities required to make and deliver goods to our doorstep or to our stores. The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic generated a large volume of supply chain issues, many of which abated as pandemic-related restrictions eased. During the last year, however, problems in the supply chain have become widespread once again, delaying the delivery of some kinds of goods. Supply chain problems go well beyond agriculture, but they have also beset agricultural producers (Gayman 2021).

The primary reason for the supply chain issues we see is that demand in the United States is growing faster than the ability of the supply chain to deliver the goods that consumers and other buyers desire. A set of interlocking problems – Covid-related shutdowns in upstream countries, labor shortages (in the US and elsewhere), high costs of freight, and the unavailability of necessary inputs at various points in the supply chain – have hamstrung the ability of suppliers to meet surging demand.

While surging demand is the primary reason for supply chain difficulties, trade policy has contributed to the problem. The tariffs imposed by President Trump make imports more expensive, and limit the availability of some goods altogether. While President Biden has taken some administrative actions to relieve supply chain difficulties, an important step that he has not taken is broad-based removal of these tariffs. Lower tariffs would reduce the price of imported goods, both final goods and inputs into US production. Lower tariffs might also generate new supply routes for imports, routes that would avoid the congested Southern California ports.

Since the problems in the supply chain are multi-faceted and interlocking, it is difficult to grasp the scale of the problem, or how long it might last. One aspect of the supply chain problem that affects export-oriented agriculture has been the run-up in freight costs, especially the costs of international shipping. A look at these costs is perhaps informative about the broader situation.

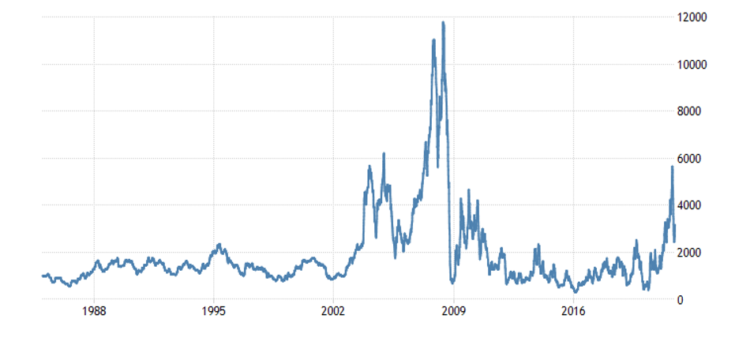

Figure 1 shows the “Baltic Dry Goods Index,” the best summary measure of the costs of moving bulk freight. Figure 1 shows the index from 1985 to the present. Looking narrowly at recent events, one can see a rapid run-up in freight prices since the end of 2020 (when the index was at approximately 1000 on the scale). Bulk freight rates peaked in October 2021 at levels that were nearly six times higher than they had been 10 months earlier. More recently, freight rates have fallen back; they are now only three times last December’s rates. It is hazardous to guess how quickly freight rates might normalize, but the history of the index offers some hope. During the Financial Crisis of 2007-8, the index was much higher than today – more than three times its current level. During that time, shipping rates came quickly off their highs, but remained volatile for a period of another two to three years. Current fluctuations are not so extreme, but we should probably take the lesson that full normalization of freight rates is unlikely to occur in 2022. It also seems likely that many of the other problems in the supply chain will ease throughout 2022, but not be completely resolved during the next year.

Figure 1. Baltic Dry Goods Index, 1985-Present

Source: https://www.marinevesseltraffic.com/1998/01/baltic-dry-index-bdi.html

China

The most difficult trade policy problem facing any U.S. President is dealing with China. Several of the international challenges that President Biden is pursuing require China’s cooperation (notably the supply chain problem, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the mitigation of climate change). But at the same time China’s is widely seen – in the US and elsewhere – as having flouted World Trade Organization rules. Since the multilateral system relies, to a large degree, on countries voluntarily adhering to commitments they have made, China’s intransigence is seen as an important challenge/threat to that system.

To date, President Biden has taken relatively few trade policy actions that relate to China directly. President Trump’s tariffs have been kept in place, but there has not been an escalation of the trade war. But there is potential friction coming. Stung by criticism of its mismanagement of the trade war, the Trump administration negotiated what they called a “phase one” agreement with China during its final year in office. This was an unusual trade agreement in that the focus was not on specific trade policy commitments from China (such as permanent reductions in tariffs on certain goods). The Trump administration instead wanted – and received – a commitment from China to purchase an additional $200 billion of US products (compared to 2017 purchases) during the years 2020 and 2021. $80 billion of the $200 billion were to be purchases of agricultural products. Bown (2021a) shows that those commitments have not been met. One question the Biden Administration will face is, what to do about this shortfall? An effort to punish China might risk a re-ignition of the trade war, exacerbating the supply chain problems. Nonetheless, it appears that the administration plans to attempt to enforce the deal (Bown 2021b).

US policy and the international trading system

One of the key ways that we should expect the Biden Administration to differ from its predecessor is its approach to managing trade relations with traditional US allies in Europe and elsewhere. President Trump’s combative approach saw US relations with these allies deteriorate. Most notably, President Trump imposed iron and steel tariffs on “national security” grounds, but nonetheless included traditional US allies in the list of exporters to be taxed. Those countries responded in kind, imposing tariffs on many US exports, including agricultural goods and food items. More importantly, the tariffs alienated countries who would have been receptive to a collective effort to respond to China’s violation of WTO rules (a collective effort would be more likely to produce results). As expected, President Biden has sought to ease tensions with traditional US allies. An October agreement with the European Union removed tariffs on imported steel from the European Union (Amaro 2021).

While the President’s handshake diplomacy with the Europeans is an important step in rebuilding the international trading system (a system that is critically important for export-oriented agriculture), the President has also pushed policies that pose risks to that system.

First, the agreement with Europe included an agreement to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum from countries that do not impose a price on carbon. While this approach makes sense as climate policy, carbon tariffs have not yet been reconciled with longstanding rules about how countries should structure their trade policies (Hayashi and Schlesinger, 2021).

Second, President Biden (along with Congress) has imposed more stringent “Buy America” provisions as part of the major infrastructure package that the President signed in November. These provisions will make the construction of new infrastructure more costly than it needs to be; they will also likely conflict with past US commitments on open trade. The legislation itself says that the new rules are not to contradict past trade agreements, but it seems unlikely that this will be true, in practice. US trading partners – especially Canada – are concerned that the new rules run counter to past agreements, and have threatened to respond in kind (Ljunggren 2021).

Summary

The international trading system is critically important for producers of export-oriented agricultural products. President Trump’s trade policy actions gravely undermined this system. One key question that was unresolved last year is what actions President Biden would take take in the wake of the chaos President Trump left him. By now, it seems clear that trade policy is not a key priority of the Biden administration, but that several other Biden Administration priorities affect, and are affected by, international trade. Some progress has been made with respect to restoring normal trade relations with Europe. But President Biden, like President Trump, appears ready to use unilateral trade policy, albeit with different goals. Unilateral trade policy has domestic political appeal, but it risks undermining the international system that rewards US agriculture so handsomely. Unilateral policies pursued over the last five years have also contributed to the current difficulties with the supply chain.

References

Amaro, Silvia (2021) U.S. and EU agree to ease metal tariffs imposed by Trump administration, CNBC, October 30.

Bown, Chad (2021a) US-China phase one tracker: China’s purchases of US goods, Petersen Institute for International Economics, November 24.

Bown, Chad (2021b) Why Biden will try to enforce Trump’s phase one trade deal with China, Petersen Institute for International Economics, October 5.

Gayman, Deann (2021) Supply chain crunches affecting agriculture — from farm to table, Nebraska Today, October 25.

Hayashi, Yuka and John Schlesinger (2021) Tariffs to Tackle Climate Change Gain Momentum. The Idea Could Reshape Industries, The Wall Street Journal, November 2.

Hillberry, Russell (2020) Trade Policy Outlook: What should we expect from a Biden Administration?, Purdue Agricultural Economics Report, December 9.

Ljunggren, David (2021) Canada, citing Buy American fears, says it might limit U.S. procurement opportunities, Reuters, October 14.