Trade: NAFTA Uncertainty Looms Over U.S. Ag

December 15, 2017

PAER-2017-16

Author: Russell Hillberry, Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics

USDA is expecting the value of agricultural exports to remain stable at $140 billion in 2018. Relatively small adjustments are expected in most Ag products. On a volume basis, wheat and corn exports are expected to be down, but higher volumes are expected for soybeans (record exports), soybean meal, beef, pork and chicken.

U.S. Ag exports are expected to be supported by somewhat faster world economic growth in 2018. The value of the U.S. dollar declined during much of 2017 and is expected to be stable to down slightly in 2018. Any weakness in the dollar would be a potential supportive factor for U.S. exports.

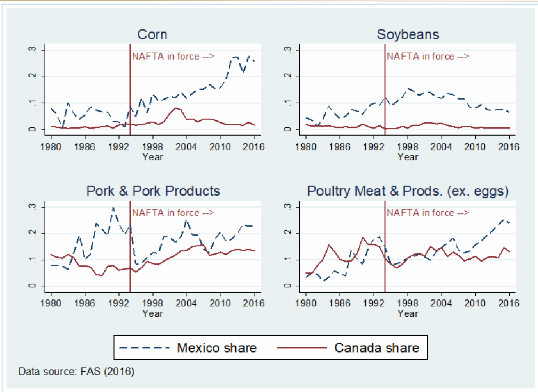

The biggest trade issue for 2018 however, is the ongoing renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Most agricultural producers will have something at stake in these talks, but corn-growers and poultry producers should be especially interested in seeing a successful conclusion of the negotiations. Figure 1 shows Mexican and Canadian shares of US exports over time for Corn, Soybeans, Pork and Poultry products. Trade shares are useful for evaluating regional trading arrangements because they show changes relative to the rest of the world. US exports in corn and poultry products have seen sizable shifts towards NAFTA markets, especially Mexico. These shifts could be reversed if NAFTA collapses.

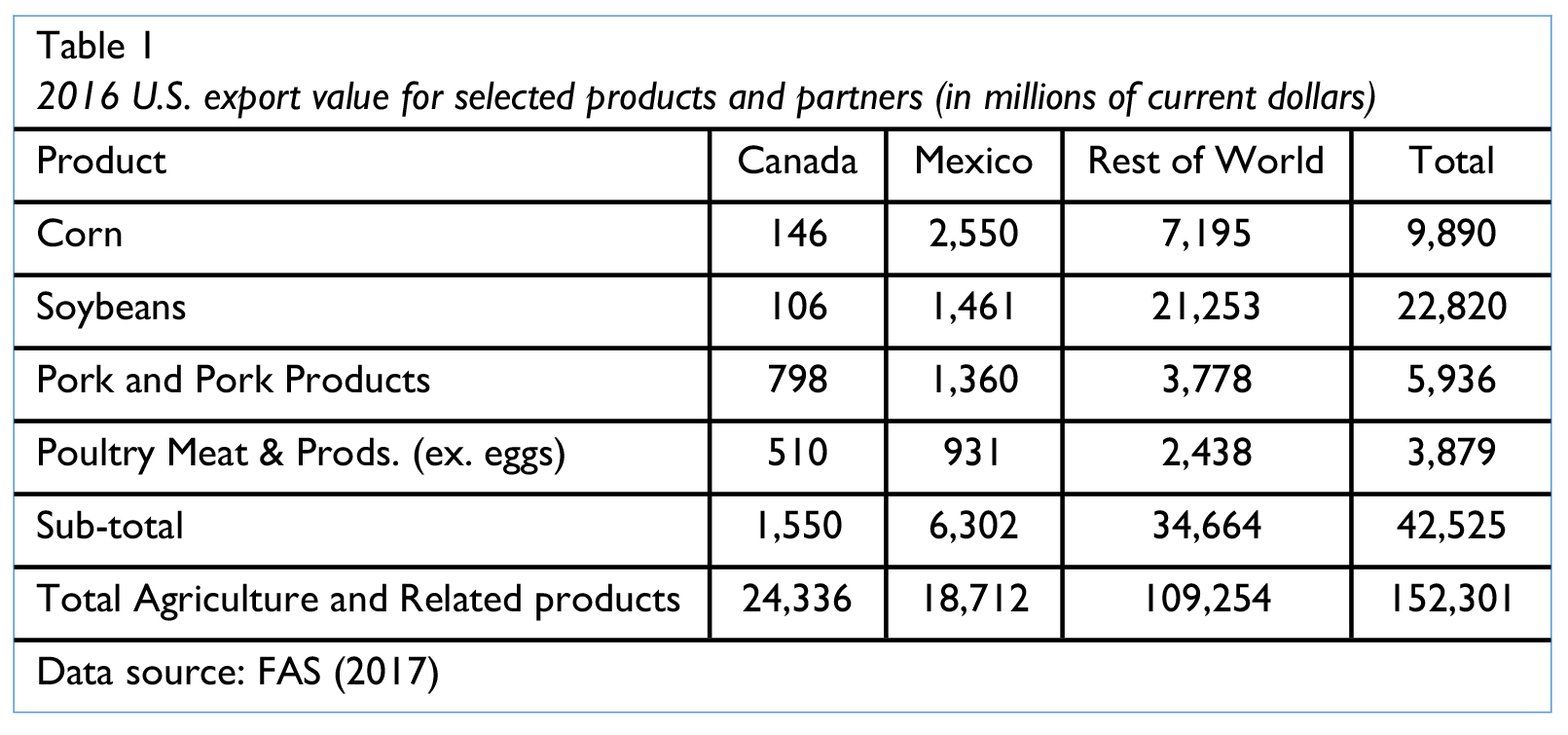

How many dollars of exports are at stake? Consider the 2016 exports in U.S. dollars shown in Table 1. Among these four product groups, US exports approached $8 billion in export value. Corn is the most significant U.S. export item under NAFTA rules, followed by pork products, soybeans and poultry. Total exports of agriculture and related products to our two NAFTA partners totaled $43 billion in 2016.

A USDA report (Zahniser et al., 2015) offers a comprehensive review of “NAFTA at 20.” The report highlights a number of developments in the Ag and food sectors that have occurred because of the agreement. In broad terms, the agreement led to increased U.S. exports of grains, oilseeds and meat products, as well as increased U.S. imports of horticultural products and sugar. Horticultural imports led to greater variety and seasonal availability of fresh produce, though they also displaced U.S. production. Cross-border Ag and food supply chains have developed under NAFTA rules, and there have been significant cross-border investments in all NAFTA member countries. Efforts by the NAFTA member countries to coordinate sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) policies has facilitated cross-border trade in live animals and in meat products.

The USDA report notes that agricultural trade between the three countries tripled over the first 20 years of the treaty. The report also showed that growth in exports of key commodities to these markets has slowed in recent years. This may mean that most of the adjustment to the provisions of the agreement have already occurred.

The agreement contains provisions for renegotiation and for withdrawal. President Trump considered a complete withdrawal of the United States from NAFTA, but was persuaded to follow the path of renegotiation instead (Donnan and Weber, 2017). It seems likely that unsuccessful negotiations would trigger the President to push for complete withdrawal. U.S. law is not clear on the question of whether the president has the legal authority to withdraw without the consent of Congress. A unilateral effort by the President to trigger withdrawal would likely result in legal action in U.S. courts (Lawder 2017) Another open question is whether U.S. withdrawal would also mean effective withdrawal from the Canada-U.S. Free Trade agreement, which pre-dated NAFTA.

Trade negotiations occur in secret, so it is not possible to know whether agreement is likely. However, the public statements of the negotiators make it seem that consensus will be difficult. U.S. chief negotiator Robert Lighthizer expressed frustration with his counterparts, who were un- willing to concede issues that had been negotiated as part of the Trans-Pacific Partnership prior to U.S. withdrawal (Bown et al., 2017). Canada’s top negotiator has called several U.S. proposals in the NAFTA negotiations “unconventional,” and argued that some were inconsistent with WTO disciplines (Keynes and Bown 2017). Most of the U.S. demands that Canadian and Mexican negotiators see as beyond-the-pale are oriented towards trade in manufactured goods. One proposal that could turn into a deal killer is the U.S. desire to include a “sunset clause,” which would trigger reconsideration of NAFTA commitments at 5-year intervals.

Whether the President’s aggressive stance in the negotiations will bear fruit is an open question. As the largest economy in the group, the U.S. may have leverage that it has not fully exploited in the past. However, Canada and Mexico have other good options. They remain members of the recently concluded Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement, for which our President withdrew the U.S. This gives them preferential access to sizable Asian Ag and food markets, most notably Japan’s. On the import side, Mexico is negotiating with Brazil and Argentina to re- place imports of U.S. corn if the NAFTA talks collapse (Webber, 2017). The disruption that U.S. withdrawal would generate for all the member countries should give the negotiators an incentive to keep talking.

In a review of the specific agricultural issues at play in the negotiations, Hendrix (2017) asks the rhetorical question, “What would a productive renegotiation of NAFTA look like?” His answer includes four issues:

- Reduce or eliminate nontariff barriers to U.S. agricultural imports, including those affecting new U.S. technologies.

- Maintain commitments to eliminate export subsidies (while also preserving food aid and export development programs).

- Seek robust rules governing sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) provisions that are sometimes used to limit imports of Ag and food products, and

- Strengthen ongoing cooperation between the agencies that oversee SPS rules in the NAFTA member countries.

Hendrix notes that many of these issues were addressed in the TPP negotiations. The smaller number of negotiating parties in the NAFTA renegotiations may produce a somewhat different outcome.

From the point of view of agricultural producers, one frustration with the way these talks are going may be the U.S. negotiators focus on manufacturing issues. There is room to improve trade relations and boost agricultural trade. However, the U.S. administration’s aggressive proposals on manufacturing-oriented trade issues risk derailing these talks. These negotiations will be one of the most critical international trade issues to watch in 2018 and can have positive or large negative impacts on U.S. agriculture depending on the outcome.

References:

Bown, Chad, Caroline Freund and Melina Kolb, 2017, “US Trade Representative `Surprised and Disappointed’ Statement from Latest NAFTA Talks—Annotated and Explained”, Petersen Institute for International Economics, Trade and Investment Policy Watch. Available at https://piie.com/blogs/trade-investment-policy-watch/us-trade-representative-surprised-and-disappointed-statement

Donnan, Shawn and Jude Webber, 2017, “Trump administration trig- gers renegotiation of NAFTA”, Financial Times, May 18. Available at https://www.ft.com/content/17bcd6da-3bdd-11e7-821a-6027b8a20f23

Economic Research Service (ERS) 2017, USDA. Outlook for U.S. Ag- ricultural Trade. AES-102, November 30, 2017. Available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/85920/aes-102.pdf?v=43069

Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) 2017, USDA. Global Agricultural Trade System, USDA, Washington, DC.

Hendrix, Cullen S., 2017, “Agriculture in the NAFTA Renegotiation,” Petersen Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief 17-24. Available at https://piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/agriculture-nafta-renegotiation

Keynes, Soumaya and Chad Bown, 2017, “NAFTA Time Out – Unsurprisingly Unconventional”, Petersen Institute for International Econom- ics Trade Talks podcast. https://piie.com/experts/peterson-perspectives/trade-talks-episode-8-nafta-time-out-unsurprisingly-unconventional

Lawder, David, 2017, “Any Trump NAFTA withdrawal faces stiff court challenge: legal experts”, Reuters, November 21. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-trade-nafta-trump-options/any-trump-nafta-withdrawal-faces-stiff-court-challenge-legal-experts-idUSKBN1DL2PK

Webber, Jude, 2017, “Mexico eyes duty-free corn deals to counter Trump,” Financial Times, March 26. Available at https://www.ft.com/content/850a886c-108c-11e7-b030-768954394623

Zahniser, Steven, Sahar Angadjivad, Thomas Hertz, Lindsay Kuberka, and Alexandra Santos (2015), NAFTA at 20: North America’s Free- Trade Area and Its Impact on Agriculture, US. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Available at https:// www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=40486.