No symbol better represents the wide reach of the Illinois–Indiana Sea Grant initiative than what the program has affectionately termed its “Two Yellow Buoys.”

Positioned in Lake Michigan, four miles off the coast of Michigan City, Indiana, and Wilmette, Illinois, these two weather buoys monitor conditions on the lake in real time. The data is used by those who enjoy the lake for recreation and commerce, researchers tracking weather and climate patterns across the Great Lakes, and educators, who use the buoys’ award-winning Twitter account as an educational tool.

Often considered the analog of the land-grant university, Sea Grant is a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration program focused on education, research and Extension related to marine and Great Lakes ecosystems.

Every state and some U.S. territories bordering an ocean or a Great Lake have a Sea Grant program. The Illinois–Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) College Program is co-administered by the University of Illinois and Purdue University and is one of only two bi-state programs in the country. The leadership for IISG changes institutions on a recurring basis, with Purdue serving as the current lead.

Tomas Höök, Purdue professor of fisheries and aquatic sciences and director of the IISG, says this kind of program is important to Great Lakes states because the lakes are the largest surface fresh water supply in the world. Effectively managing these ocean-like systems is critical for the region.

The Great Lakes face numerous threats, especially Lake Michigan, which is where most IISG research takes place. Key threats include invasive species, nutrient runoff , contamination and climate change. Although the list is not exhaustive, Höök warns, these four issues have the greatest potential to derail the many communities, businesses and industries that rely on the Great Lakes.

IISG’s work involves efforts to better understand and stymie all these threats and find new ways to protect and preserve Lake Michigan.

If you ask fishery managers to identify the greatest threat to the Great Lakes, they often point to invasive species. Estimates indicate invasive species cause over $5 billion in economic damage to the Great Lakes each year.

“As an example, the invasive alewife fish experiences huge die-off events. This can clog up water valves, which can be problematic, for instance, for nuclear power plants around the Great Lakes, because that water is used in their cooling systems. Some plants have had to shut off so they don’t overheat when this happens, which comes at high economic cost,” Höök says.

Hundreds of invasive species live in Lake Michigan, from the water-valve clogging variety to the microscopic. Some of the most prevalent species include zebra and quagga mussels, sea lamprey, alewife and the spiny water flea. There is great concern that new invaders, such as the well-documented Asian carp, will arrive soon. Invasive species find their way into the lake through many pathways: artificial canals, accidental or intentional introduction, and through ballast water of freight ships, which navigate through man-made canals, potentially from across the Atlantic.

Invasive species present several dangers to the Great Lakes. They prey on native animals, as the sea lamprey does, or filter nutrients out of the water that other species require to survive. This creates long-term havoc in the ecosystem and alters the food web.

“Suitable fish habitat is a major issue in areas like Saginaw Bay in Lake Huron, in that there often isn’t enough available,” says Mitchell Zischke, Purdue fisheries specialist and clinical assistant professor in forestry and natural resources. “Invasive species have a hand in degrading these habitats, preventing native species from laying eggs or foraging for food there. In Lake Michigan, the biggest threat from invasive species is their domination of the food web and fisheries.”

By documenting the impact invasive species have in Lake Michigan, scientists with IISG can use their research to enhance educational and outreach campaigns aimed at the public and stakeholders, offering information about the damage they cause and how best to prevent their introduction and spread.

One of the most obvious changes to Lake Michigan and other parts of the Great Lakes over the past 150 years has been the loss of suitable fish habitat, Zischke says. The impacts of invasive species, pollution, the filling of coastal wetlands and damming rivers can all lead to habitat loss. However, a major culprit is sediment and nutrient runoff caused by erosion and aggressive land use practices.

“In some areas of the Great Lakes, terrestrial sedimentation has covered much of the rocky areas where fish like to spawn,” he explains.

A change in land-use practices and increased education about terrestrial sediment has decreased some of the damage, but Zischke and colleagues continue to monitor areas impacted by sediment.

“A few years ago, we wanted to see if fish were trying to spawn in areas covered by sediment,” Zischke says of a project in Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron. “The decision-making of where to spawn can be passed on genetically, so some fish might be hardwired to spawn there.

This project helped us understand where to focus restoration efforts and also gave us baseline data to help measure the project’s success.”

While the cause of nutrient runoff is similar to that of sedimentation, the effects are different.

“Runoff can carry nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus from urban and agricultural areas into water bodies and impact water quality,” Eliana Brown, stormwater specialist and water quality Extension Specialist at the University of Illinois, explains. “In the Great Lakes, phosphorous loads in particular can create conditions favorable to algal blooms, some of which are harmful.”

Large algal blooms can create a condition called hypoxia, a sharp drop in oxygen levels when the blooms die off , making large zones of lakes inhospitable for much aquatic life. This is common in areas like Green Bay, Saginaw Bay and Lake Erie, where a huge hypoxic area forms in the middle of the lake every summer and fall. In addition, certain algal blooms can spoil water quality by producing odors or a thick scum and can be highly toxic to humans and other animals. Such blooms in western Lake Erie have led to huge problems, including shutting down water supplies to the city of Toledo.

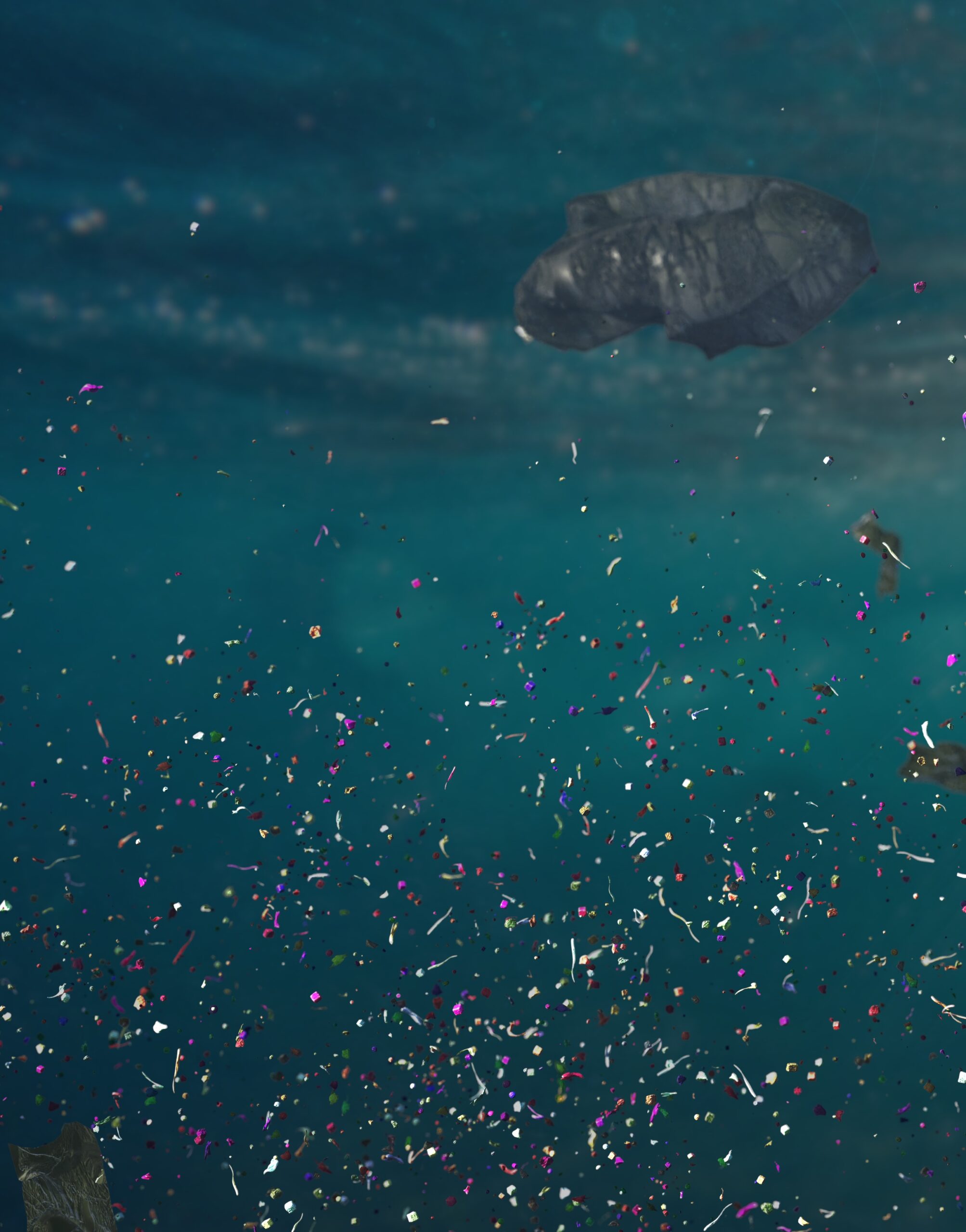

While sediment can act as a Trojan horse, introducing toxins to Lake Michigan, pollutants are also introduced in other ways, ranging from everyday individual actions to industrial output.

“Anthropogenic contaminants, introduced by human activity, have been present in the Great Lakes for a long time,” Höök says. “People have been dumping contaminants there, intentionally and unintentionally, for many years.”

Many of the contaminants come from the usual suspects: heavy metals and toxins that leach into the soil from industry, chemical and nutrient runoff from farmland that flanks large sections of Lake Michigan, and water pollution from boats and recreational activities. While regulations and conservation efforts have reduced the pollution finding its way into the Great Lakes, they have by no means eliminated contamination.

New contaminants are always emerging, including pharmaceuticals and microplastics, which enter waterways from residential areas. (Microplastics measure less than five millimeters, about the size of a sesame seed; one example is the exfoliating microbeads in beauty products.) IISG works to curtail contamination using public education about the use of washing machine filters to sieve out microplastics and how to dispose of pharmaceuticals and other chemicals. (For example: don’t flush them down your toilet; instead see unwantedmeds.org.)

Climate change is an undercurrent that exacerbates many of the other risks posed to the Great Lakes, including invasive species, contamination and runoff. However, as Höök points out, unraveling the impact of climate change from other threats can be difficult and challenging to measure in absolute terms.

“There are some species that are actually going to do better in warmer water, but there are others that won’t do as well, so trying to understand the direct impact on entire ecosystems can get tricky,” he explains.

Veronica Fall, climate Extension specialist with the University of Illinois and a member of the Sea Grant team, says changing and variable lake levels are two of the main threats climate change poses to Lake Michigan and other Great Lakes. Data over the past few years show record high lake levels and an unprecedented rate of increase. While the highest-ever lake level on Lake Michigan was achieved in 1986, levels in the lake continue to set monthly highs at a rate previously unseen. The severe and visible effects include erosion around the lake and its basin, as well as extensive flooding.

“We are seeing erosion along the coastline in the winter months because of rising temperatures,” Fall says. “When ice covers the lake, it keeps things in place and protects the shoreline from winds and waves. With rising temperatures, there is less ice, which means the shorelines get battered.”

Documenting these effects and sharing findings with communities is a key part of Fall’s job as an Extension specialist. Her role is less about convincing people climate change is real and more about preparing them for the difficult environmental and economic choices they will have to make in the coming decades as climate change extracts its toll on waterfront communities.

Some of the individuals and communities that will be most impacted by climate change are those that Fall and Zischke work with every day. Charter boat operators rely on a healthy fish population to sustain their clientele.

- Every state bordering a Great Lake has a Sea Grant program, which focuses on education, research and Extension about Great Lakes ecosystems. The Illinois–Indiana Sea Grant concentrates on Lake Michigan, and is currently administered by Purdue University, led by Professor Tomas Höök.

- Its weather buoys monitor conditions on the lake for recreation and commerce, to track weather and climate patterns, and as a teaching tool.

- Sea Grant–funded researchers and Extension specialists examine key threats to Lake Michigan and the Great Lakes as a whole to better protect and preserve them. Threats include:

- Invasive species, which can prey on native species, filter out important nutrients and clog water intakes.

- Sedimentation of rocky areas that prevents fish from spawning and nutrient runoff that can create harmful algal blooms and hypoxic dead zones.

- Other damaging contaminants, including industrial production, farmland runoff, pharmaceuticals and microplastics.

- The impacts of climate change, including variable lake levels and an increase in coastline erosion during winters with less ice.

- Sea Grant Extension specialists use research findings to inform educational and outreach campaigns and to offer practical, actionable advice to stymie threats to the lake’s ecosystem.

- Their research, Extension and communication efforts are key to protecting Lake Michigan as a tourist attraction, water supply and economic driver for the communities that surround it.

Small recreational businesses, from golf courses to vineyards, are at risk as flooding and volatile weather become more frequent. Communities around the lake rely heavily on the tourism supported by the abundance of accessible sandy beaches. If activity dwindles, these economies begin to erode.

These are the realities Fall communicates, while also imparting practical, actionable advice to avoid worst-case scenarios. That advice could include drafting a climate action plan or passing local zoning regulations, as there is no uniform solution to climate change, Fall says, even in the microcosm of Lake Michigan.

“We provide information about how communities can build resilience to climate change, which means outlining short- and long-term impacts,” Fall says.

Understanding and caring for Lake Michigan requires understanding and caring for the densely populated communities that surround and rely on it.

“The lakes are so important for all sorts of reasons,” Höök says. “People live and recreate on them, there’s a huge tourist industry built up around the lakes, and we take tons of water out of them for drinking, industry and agriculture — about 60 billion gallons per year. They’re a huge economic driver in the region. The sport fishing business on the lakes has been estimated around $7 billion a year and the Great Lakes are a major nexus for trade and shipping.”

The ecosystems of the Great Lakes intertwine with the economies and environments of the states they border, which is positive when the lakes are thriving but alarming when they are under threat.

“All of the benefits the Great Lakes provide are also all the things that are at risk,” Höök says. “By connecting decision makers with our specialists, our research and Extension efforts move quickly from theoretical to applicable. Constant communication and collaboration between scientists and stakeholders are the best chances we have in responding to climate change and other stressors facing the Great Lakes.”

Purdue Agriculture, 615 Mitch Daniels Blvd, West Lafayette, IN 47907-2053 USA, (765) 494-8392

© 2024 The Trustees of Purdue University | An Equal Access/Equal Opportunity University | USDA non-discrimination statement | Integrity Statement | Copyright Complaints | Maintained by Agricultural Communications

Trouble with this page? Disability-related accessibility issue? Please contact us at ag-web-team@purdue.edu so we can help.